![]()

Part 1

Introduction

A commitment to doing the right thing is no guarantee of winning in the marketplace, but over the past 30 years numerous companies have demonstrated that you can simultaneously build a better world and the bottom line. Experience has also shown that creating successful marketing and corporate social initiatives requires intelligence, commitment, and finesse. Whether you work for a Fortune 500 giant or a start-up, generating financial profits and social dividends is a delicate balancing act. For many businesspeople, it proves to be among the most satisfying chapters of their professional lives.

If you are reading this introduction, there is a good chance you work in a company's department of community relations, corporate communications, public affairs, public relations, environmental stewardship, corporate responsibility, or corporate citizenship. Or you may be a marketing manager or a product manager, have responsibility for some aspect of corporate philanthropy, or run a corporate foundation. It is also quite possible that you work in a public relations, marketing, or public affairs agency and that your clients are looking to you for advice on marketing and corporate social initiatives. You may be the founder of a new business or the CEO of a large, complex enterprise.

If you are like others in any of these roles, it is also quite possible that you feel challenged and pulled by the demands and expectations surrounding the buzz for corporate social responsibility. You may be deciding what social issues and causes to support (and which ones to reject). You may be screening potential cause partners and determining the shape of your financial, organizational, and contractual relationships with them. You may be stretched by the demands of selling your ideas internally, setting appealing yet realistic expectations for outcomes, and building cross-functional support to bring programs to life. Or perhaps you are currently facing questions about what happened with all the money and resources that went into last season's programs.

If any of these challenges sound familiar, we have written this book for you. Dozens of your colleagues in firms around the world such as Allstate, Johnson & Johnson, Levi Strauss & Co., Marks & Spencer, Patagonia, PepsiCo, Starbucks, Subaru, TELUS, and TOMS have taken time to share their stories and their recommendations for how to do the most good for your company as well as for a cause.

Years of experience and months of research have strengthened our belief that doing well by doing good is more than just a catchy phrase. Corporations that apply rigor to creating effective marketing and corporate social initiatives can help build a better world and enhance their bottom line.

Even though this book has been written primarily for those working on behalf of for-profit corporations, it can also benefit those in nonprofit organizations and public sector agencies seeking corporate support and partners to realize their missions. It offers a unique opportunity for you to gain insight into a corporation's wants and needs and prepares you to decide which companies to approach and how to approach them. The final chapter, written just for you, presents recommendations that will increase your chances of forging successful cross-sector alliances.

Our aspiration for this book is that it will better prepare corporate managers and staff to choose the most appropriate issues, best partners, and highest potential initiatives. We want it to help you engender internal enthusiasm for your recommendations and inspire you to develop programs worthy of future case studies. And, perhaps most important, we hope it will increase the chances that your final report on what happened will feature incredibly good news for your company and your cause.

![]()

Chapter 1

Good Intentions Aren't Enough: Why Some Marketing and Corporate Social Initiatives Fail and Others Succeed

When we come out of this fog, this notion that companies need to stand for something—they need to be accountable for more than just the money they earn—is going to be profound.1

—Jeffrey Immelt, Chairman and CEO, General Electric

At the November 2008 Business for Social Responsibility Conference

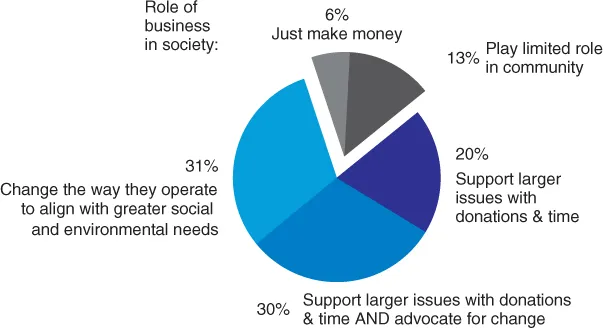

In the oft-cited 1970 article The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, economist Milton Friedman argued that business leaders had “no responsibilities other than to maximize profit for the shareholders.”2 Four decades later, the public statements of corporate leaders such as General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt quoted above and surveys of the general population indicate Friedman's argument is far from the majority view. A 2011 global consumer study by Cone Communications found only 6 percent of consumers in 10 countries agreed with the philosophy that the role of business in society is to “Just make money”3 (see Figure 1.1).

More recently, Harvard's Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer have argued that businesses must adopt a “shared value” mindset that seeks out and capitalizes on business opportunities to create “economic value in a way that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges.”4 They criticize most companies for being “stuck in a ‘social responsibility’ mind-set in which societal issues are at the periphery, not the core.”5

One need not be a follower of Friedman, Porter, or Kramer to agree that some activity carried out over the years in the name of social responsibility has been poorly conceived and ineffective at producing benefits for the companies or causes involved. Conceptualizing, creating, executing, and evaluating marketing and corporate social initiatives is challenging work. This book is intended to be a practical management guide for the executives tasked with allocating scarce resources to strategically craft policies and programs that do good for their companies and their communities.

We will distinguish six major types of marketing and corporate social initiatives and provide perspectives from professionals in the field on strengths and weaknesses of each in terms of benefits to the cause and benefits to the company. We've divided these initiatives into two groups: those that are marketing-oriented (cause promotion, cause-related marketing, and corporate social marketing) and those that more broadly express and advance corporate values and objectives (corporate philanthropy, workforce volunteering, and socially responsible business practices). To firmly familiarize you with the breadth of options, Chapter 2 provides an overview of the six types of initiatives and then each is covered in depth in its own chapter. (It should be noted that in practice, many programs are hybrid combinations of several initiative strains.)

Then we will guide you through recommended best practices for choosing among the varied potential social issues that could be addressed by a corporation; selecting an initiative that will do the most good for the social issue as well as the corporation; developing and implementing successful program plans; and evaluating program efforts.

This opening chapter sets the stage by providing a common language for the rest of the book. We highlight trends and statistics that demonstrate that corporations have an increased focus on social responsibility; describe the various perceived factors experts identify as fueling these trends; and conclude with current challenges and criticisms facing those attempting to do the most good.

What Is Good?

A quick browse of Fortune 500 websites reveals that the umbrella concept of good has many names including: corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, corporate philanthropy, corporate giving, corporate community involvement, community relations, community affairs, community development, corporate responsibility, global citizenship, and corporate societal marketing.

For purposes of this focused discussion and applications for best practices, we prefer the use of the term corporate social responsibility and offer the following definition:

This definition refers specifically to business activities that are discretionary as opposed to practices that are mandated by law or are moral or ethical in nature and perhaps, therefore, expected. We are referring to a voluntary commitment a business makes to choose and implement these practices and make these contributions. It will need to be demonstrated in order for a company to be described as socially responsible and will be fulfilled through adoption of new business practices and/or contributions, either monetary or nonmonetary. And when we refer to community well-being, we are including human conditions as well as environmental issues and communities from local to global that are defined by geography, demographics, challenges, aspirations, and many other factors.

We use the term marketing and corporate social initiatives to describe major efforts under the corporate social responsibility umbrella and offer the following definition:

Causes most often supported through these initiatives are those that contribute to community health (i.e., AIDS prevention, early detection for breast cancer, timely immunizations); safety (i.e., designated driver programs, crime prevention, use of car safety restraints); education (i.e., literacy, computers for schools, special needs education); employment (i.e., job training, hiring practices, plant locations); the environment (i.e., recycling, elimination of the use of harmful chemicals, reduced packaging); community and economic development (i.e., low-interest housing loans, mentoring entrepreneurs); and other basic human needs and desires (i.e., hunger, homelessness, protecting animal rights, exercising voting privileges, anti-discrimination).

Support from corporations may take many forms including cash contributions, grants, promotional sponsorships, technical expertise, in-kind contributions (i.e., donations of products such as computer equipment or...