eBook - ePub

A Companion to Roman Architecture

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Roman Architecture

About this book

A Companion to Roman Architecture presents a comprehensive review of the critical issues and approaches that have transformed scholarly understanding in recent decades in one easy-to-reference volume.

- Offers a cross-disciplinary approach to Roman architecture, spanning technology, history, art, politics, and archaeology

- Brings together contributions by leading scholars in architectural history

- An essential guide to recent scholarship, covering new archaeological discoveries, lesser known buildings, new technologies and space and construction

- Includes extensive, up-to-date bibliography and glossary of key Roman architectural terms

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Roman Architecture by Roger B. Ulrich, Caroline K. Quenemoen, Roger B. Ulrich,Caroline K. Quenemoen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Italic Architecture of the Earlier First Millennium BCE

Introduction

The origins of Roman architecture have long been sought, as its iconic and widespread form exerts influence even in the post-modern world. Recent scholarship has addressed the role played by social processes in the generation of a recognizably Roman material culture and places this phenomenon toward the end of the first millennium BCE (Elsner 1995b; Hölscher 2004; Stewart 2008). These studies are immensely valuable for examining the material culture of the Roman Republic and the ensuing imperial period, yet this same culture may be set in an even sharper focus by situating it against the background of deeply rooted Italic traditions that inform, at least in part, the aspects that make it “Roman.” This chapter will examine the underpinnings of Roman architecture by exploring some critical issues related to the architecture of central Italy primarily during the first half of the first millennium BCE. Four categories of buildings will be considered, namely domestic structures, civic buildings, fortifications, and sacred architecture. It can be shown that over the first half of the first millennium BCE, a tradition of indigenous construction emerged with characteristics of material and form that would continue to have a marked influence on architectural design throughout Roman history.

Roman authors in the Late Republic also sought to explain the origins of their society. Notions about the origins of architectural design received their due, especially from Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (d. after 15 BCE), whose De Architectura outlines numerous conventions that recommend (if not dictate) the way in which buildings of his time should be constructed. These writers of the late republic were, in most cases, speculating on an ancient past for which they had relatively little source material, especially in the case of scholars like Varro. One question that perhaps escaped – or did not even occur to – the minds of these writers was the degree to which the remote Italo-Roman past, a time prior to the direct contact Romans had with the Greek world from the third century BCE onwards, had much in common with the Rome of their own day.

In a curious way, archaeologists and architectural historians whose aim it is to trace the trajectory of the architectural forms and built environments of the Roman world often find themselves in a situation akin to that of Vitruvius and his contemporaries – seeking an aetiological explanation but having only fragmentary source material representative of diverse cultures occupying the Italic peninsula and spanning several centuries. It was both trade and Italy’s first wave of urbanism that brought regional pockets of culture into sustained contact with one another and with a wider Mediterranean world through the agency of Punic and Greek traders. From a certain point of view, the identity question begins as early as the Orientalizing period when attractive eastern imports flooded into Italy; from that point on, separating the indigenous from the imported becomes a challenge, one that carries forward into the Roman culture of the later first millennium BCE and beyond.

This chapter offers some comments on the nature of the architecture of the Italian peninsula prior to the Hellenistic period and asks questions about the nature of indigenous architectural forms. Recent scholarly approaches to the archaeology of peninsular Italy have focused on regional (and even micro-regional) approaches that have dealt with settlement typology, economy, and identity, but to this point a similar treatment of architectural morphology has yet to materialize. It will prove constructive to examine the architectural traditions of central Italy across the first millennium BCE, concentrating, in this case, on forms leading up to the beginnings of the Roman conquest in the fourth century BCE and commenting on what connections may be drawn between forms across this broad timeframe. While the architecture of the bulk of first-millennium-BCE Italy is quite different, both in form and conception, from the “Roman” architecture of the first century BCE and later, one can argue that there are nevertheless elements of form that are persistent.

1. Early Domestic Architecture

In peninsular Italy, domestic architecture is the natural place at which to begin this discussion. During the Final Bronze Age (ca. 1150–950 BCE), in population centers connected with the Apennine culture across the Italian peninsula, the most basic form of building is a fairly ephemeral hut constructed of wattle-and-daub and thatch with a beaten earth floor. At Sorgenti della Nova near Viterbo, Italy, several oblong buildings, constructed in wattle-and-daub with thatched roofs, occupy a settlement organized on a system of terraces (Negroni Catacchio 1983; Negroni Catacchio and Cardosa 2007). These buildings, sometimes referred to as “long houses,” are similar to remains from the sites of Luni sul Mignone and Monte Rovello. In all cases the structures are large (15 to 17 m x 8 to 9 m), leading scholars to speculate that they may represent the dwellings of elites who enjoyed higher social standing (Bartoloni 1989: 69–70; on Monte Revello, Biancofiore and Toti 1973; on Luni sul Mignone, Hellström 1975).

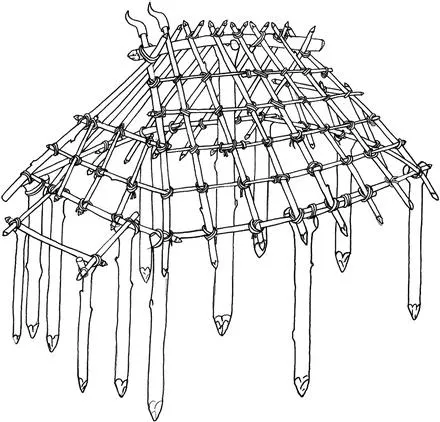

Iron Age huts are well attested at the sites of what would become the great urban centers of archaic Italy, and, in a sense, those of Rome’s Palatine Hill settlement have become something of an icon in and of themselves for Iron Age Italy (Figure 1.1). Among these, the so-called tugurium Romuli (hut of Romulus) was even iconic for ancient Romans who maintained it from the first century BCE onward as a reminder of their mythical founder (Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 1.79; Vitr. De Arch. 2.1.5).

Figure 1.1 Reconstruction of an Iron Age hut. Source: Ulrich 2007: 92, fig. 6.1.

The footprint of these huts could be either rectangular or ovoid with a sunken floor and a superstructure that relied on vertical wooden posts to support a pitched roof covered in thatch; the walls are formed of wattle-and-daub. From a technical point of view this method involves a woven lattice of wooden strips or twigs (wattle) over which a mud plaster (daub) is applied. This plaster is highly variable in its composition, but can include wet soil or clay that can in turn be tempered with animal dung, straw, or sand. Wattle-and-daub is the likely precursor to the later Roman “in-fill” technique (opus craticium), known to Vitruvius (De Arch. 2.8.20) and employed in low-cost buildings, for example, urban insulae of Herculaneum, up to the first century CE. The continuity of this essentially static technique in modern Italy has been well documented (Shaffer 1993; Brandt and Karlsson 2001).

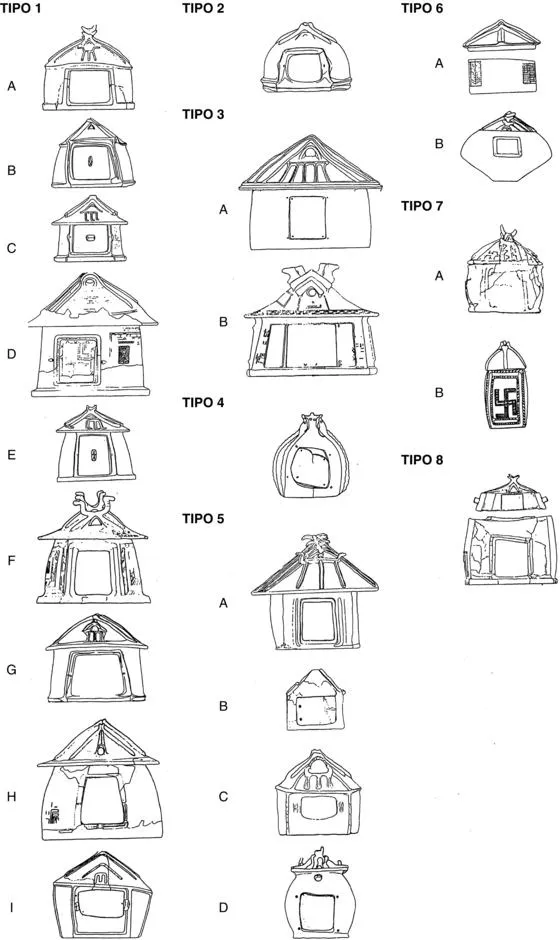

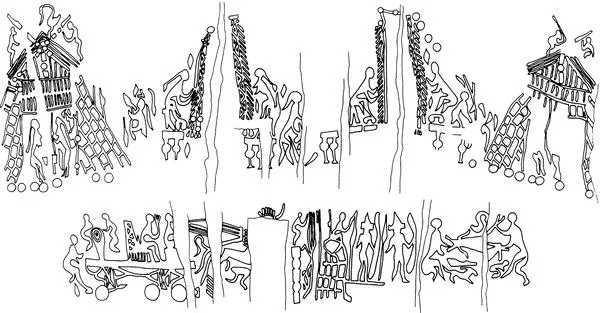

Terracotta cinerary urns modeled to resemble huts, and thus referred to as “hut urns,” provide a significant evidentiary body for the form and decoration of Iron Age huts (Bartoloni et al. 1987). These urns, characteristic of Latium and South Etruria, correspond closely with the archaeological remains of actual huts (Figure 1.2). An urn from Vulci, taken along with others, makes the case for the actual huts having sunken floors, as archaeological remains can confirm (Bartoloni 1989: 113, Figure 5.5). The exterior surfaces of the urns tend to be decorated with linear motifs common in the Geometric period (ninth to eighth centuries BCE) while the stylized roofs include zoomorphic termini, which may reflect the superstructures of actual huts and emphasize the ridgepole. The patterns of geometric decoration tend to emphasize exterior fasciae and to concentrate on framing door and window openings. A domestic scene with two huts carved into the Verucchio Throne, dated to the first half of the seventh century BCE, also depicts the ridge log of the roof carved with birds and monkeys (Haynes 2000: 41) (Figure 1.3). In addition to offering a better understanding of actual huts, the urns also highlight the important social status of hut owners in the Iron Age. The relative infrequency of these urns in the funerary record suggests that those whose remains are contained therein enjoyed a higher than average social position.

The seventh and sixth centuries BCE brought substantial social change to central Italy and revolutionary, concomitant changes in the forms of both structures and settlements. The radical phenomenon that acts as catalyst in this period is urbanism, the emergence of the first true cities in archaic Italy (Gros and Torelli 2010). In Etruria, Latium, and Rome, this process creates large nucleated centers with substantial territorial catchment areas; the social elite and their control of territory is key to the emergence of these cities (Smith 2006; Terrenato 2011). The advent of city centers also results in the differentiation of architectural typologies in that now one can speak of the dichotomy of urban and rural architecture. In addition to the rise of elites and their culture, another key outcome of urbanism is interconnectivity, both of cities within Italy and between Italian cities and the wider Mediterranean world through the agency of Punic and Greek traders and Greek colonists in Sicily and Magna Graecia. The influx of imported goods for elite consumption affected the nature of Italic architecture and material culture.

Figure 1.2 Iron Age hut urns. Source: Bartoloni et al. 1987: fig. 96.

Figure 1.3 Drawing of the scene from the Verucchio throne. Source: Swaddling et al. eds. 1995: 175, fig. 5.

While huts remained popular into the seventh century BCE, more elaborate, multi-roomed houses with rectilinear plans gradually replaced them in central Italy. Although the reasons for this shift in design from circular to rectangular structures continues to be debated (e.g., Hodges 1972), many scholars have suggested that it may be related to the greater suitability of rectangular structures within the framework of urbanized settlements, as well as to technical issues of construction. The emergence of houses with square or rectangular footprints in Etruria occurs across the seventh century BCE (Izzet 2007: 148) and is coincident with the emergence of cities with grid plans, for instance Gabii in Latium and Marzabotto in the Po plain (Govi 2007; Becker, Mogetta, and Terrenato 2009). These early rectilinear houses were built upon a stone socle with walls constructed of a variety of materials, including stone and brick (Izzet 2007: 152). Internal walls, also built from permanent materials, can now be clearly recognized within the nearly square houses. Some of the earliest known houses in Etruria with internal divisions date to seventh-century Acquarossa and sixth-century San Giovenale. These houses had either two or, in some instances, three rooms (Izzet 2007: 158). Houses with increasingly more rooms appear in sixth-century and later contexts, such as a house from Marzabotto (early fifth century) that had 16 “articulated spaces” (Izzet 2007: 158, Figure 5.6; see further discussion below). The appearance of internal articulation suggests a diversification of function within the domestic sphere and an increasing complexity of community life, both surely a byproduct of urbanism. As house plans in Italy develop further, the incorporation of axiality and bilateral symmetry become important, perhaps influenced strongly by Hellenic models (reviewed by Sewell 2010: Chapter 4).

At Lago dell’Accesa, a mining settlement in the territory of Vetulonia, there is also substantial evidence for houses of the early sixth century BCE. Clusters of domestic architecture were discovered wherein each cluster of approximately 10 houses had its own corresponding necropolis (Steingräber 2001: 299). These houses are characterized by a ground plan that incorporated two or three rooms accessed by means of a vestibule. The houses at Lago dell’Accesa are of great interest from the morphological point of view as they have moved away from the ovoid ground plan of huts like those at San Giovenale to a more rectilinear plan, albeit still quite irregular. The adoption of this new building practice becomes more pervasive across the sixth century BCE, and it is evident in various forms in the farm at Podere Tartuchino (Attolini and Perkins 1992) and also in the area known as Zone F at Acquarossa (Östenberg 1975). In some cases, the settlements of this time period tend to be quite densely occupied and without any regular plan or organization. At Acquarossa there is evidence for a fairly dense occupation with some 70 “longhouses” and “broadhouses” discovered in a 1 hectare area of the site (Steingräber 2001: 297).

Given the relative scarcity of archaeological evidence for houses, especially those in urban contexts, during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, Etruscan rock-cut tomb architecture has long provided another source of surrogate evidence. The chamber tombs of the Banditaccia necropolis at Caere, to cite a famous example, began in the Orientalizing period and included early tombs such as the Tomba della Capanna (early seventh century BCE) whose interior styling seems to take its cue from the interior architecture of Etruscan houses (Prayon 1975; 1986; 2010). From the seventh to the sixth centuries BCE, the interior architecture of Etruscan tombs at Caere becomes increasingly more elaborate, providing further evidence not only of interior décor, but also of interior architectural details, including roof beams and moldings, which are often used to reconstruct visions of the interiors of actual Etruscan houses. While the tumuli of Caere are circular in plan, the interior tomb plans are typically rectilinear. They tend to include key elements like a dromos, vestibule, main hall, and tomb chambers with funeral biers, all organized in a linear arrangement. At Caere and Tarquinia the tomb chamber is often carved directly from the bedrock.

Connected to the issue of Etruscan tombs as surrogate evidence for domestic architecture is the debate over the development of the internal articulation of domestic buildings in the archaic period. Since many tomb chambers have both vestibules and main halls, the question of the origins of the Italic atrium naturally arises (see Chapter 18). While some scholars look to the Greek world for models that inspired the development of the classic atrium in Italy (Torelli 2012), during the sixth century, we find spaces in both urban and rural houses that may be identified as precursors to this central organizing feature of the later Roman house. The “House of the Impluvium” at Rusellae, built in the middle of the sixth century BCE over an earlier structure, features a tetrastyle courtyard (ca. 300 m2) that contains a well. Donati connects this layout with the atrium tetrastylium discussed by Vitruvius and reconstructs a roofing system akin to those of late republican impluviate houses (Donati 1994). A portico framed the entry to the structure, and there was a sort of banqueting room, as well as a dedicated space for food preparation as indicated by the presence of a grinding stone, fireplace, and a small larder. At Gonfienti (Comune di Prato) the recent discovery of an Etruscan house dating to the late sixth to early fifth century BCE and with a footprint of 1,270 m2 serves to reinvigorate the discussion about archaic houses in central Italy (Poggesi 2004; Cifani 2008: 275; Poggesi et al. 2010). This structure has a quadrangular plan centered on an internal, impluviate courtyard; at the back is a series of rooms.

The houses at Marzabotto, situated in the Po Plain, offer nearly unique evidence for domestic architecture of the late sixth to early fifth centuries BCE (Govi 2007; Bentz and Reusser 2008). The site’s status as the only purported Etruscan colonial foundation marks it as something of an unusual example of Italic urbanism, for the most part because it remains without adequate comparanda. While Marzabotto’s regularized layout continues to be a topic of scholarly debate, the recently discovered grid plan in the Latin city of Gabii provides a possible near chronological parallel for the evidence at Marzabotto (Becker, Mogetta, and Terrenato 2009). Regardless of the origins or rationale of the site’s plan, the blocks (insulae) contain up to eight houses each and measure 150 m in length; the houses in turn share a common facade along the street. These houses, like Gonfienti and Rusellae, are internally articulated and include a large courtyard (Cifani 2008: 277). Part of this discussion, but resting on less secure evidence, are the domus excavated by Carandini on the north slope of the Palatine Hill in Rome (Carandini and Carafa 1995). Here the structure labeled as “house 3” is advanced as a proto-typical atrium house of the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, although this hypothesis has been put forth on the basis of ins...

Table of contents

- Cover

- BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- Contributors

- Maps/General Images

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE: Italic Architecture of the Earlier First Millennium BCE

- CHAPTER TWO: Rome and Her Neighbors: Greek Building Practices in Republican Rome

- CHAPTER THREE: Creating Imperial Architecture

- CHAPTER FOUR: Columns and Concrete: Architecture from Nero to Hadrian

- CHAPTER FIVE: The Severan Period

- CHAPTER SIX: The Architecture of Tetrarchy

- CHAPTER SEVEN: Architect and Patron

- CHAPTER EIGHT: Plans, Measurement Systems, and Surveying: The Roman Technology of Pre-Building

- CHAPTER NINE: Materials and Techniques

- CHAPTER TEN: Labor Force and Execution

- CHAPTER ELEVEN: Urban Sanctuaries: The Early Republic to Augustus

- CHAPTER TWELVE: Monumental Architecture of Non-Urban Cult Places in Roman Italy

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Fora

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Funerary Cult and Architecture

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Building for an Audience: The Architecture of Roman Spectacle

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Roman Imperial Baths and Thermae

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Courtyard Architecture in the Insulae of Ostia Antica

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Domus/Single Family House

- CHAPTER NINETEEN: Private Villas: Italy and the Provinces

- CHAPTER TWENTY: Romanization

- CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: Streets and Facades

- CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: Vitruvius and his Influence

- CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: Ideological Applications: Roman Architecture and Fascist Romanità

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: Visualizing Architecture Then and Now: Mimesis and the Capitoline Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: Conservation

- Glossary

- References

- Index