- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Sustainable Healthcare Architecture

About this book

"With this book, Robin Guenther and Gail Vittori show us how critical our green building mission is to the future of human health and secures a lasting legacy that will continue to challenge and focus the green building movement, the healthcare industry, and the world for years to come."

—From the Foreword by Rick Fedrizzi, President, CEO and Founding Chair, U.S. Green Building Council

INDISPENSABLE REFERENCE FOR THE FUTURE OF SUSTAINABLE HEALTHCARE DESIGN

Written by a leading healthcare architect named one of Fast Company 's 100 most creative people in business and a sustainability expert recognized by Time magazine as a Green Innovator, Sustainable Healthcare Architecture, Second Edition is fully updated to incorporate the latest sustainable design approaches and information as applied to hospitals and other healthcare facilities. It is the essential guide for architects, interior designers, engineers, healthcare professionals, and administrators who want to create healthy environments for healing.

Special features of this edition include:

- 55 new project case studies, including comparisons of key sustainability indicators for general and specialty hospitals, sub-acute and ambulatory care facilities, and mixed-use buildings

- New and updated guest contributor essays spanning a range of health-focused sustainable design topics

- Evolving research on the value proposition for sustainable healthcare buildings

- Profiles of five leading healthcare systems and their unique sustainability journeys, including the UK National Health Service, Kaiser Permanente, Partners HealthCare, Providence Health & Services, and Gundersen Health System

- Focus on the intersection of healthcare, resilience, and a health promotion imperative in the face of extreme weather events

- Comparison of healthcare facility-focused green building rating systems from around the world

Sustainable Healthcare Architecture, Second Edition is an indispensable resource for anyone interested in the design, construction, and operation of state-of-the-art sustainable healthcare facilities.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART 1

CONTEXT

Chapter 1

DESIGN AND STEWARDSHIP

DAVID ORR

INTRODUCTION

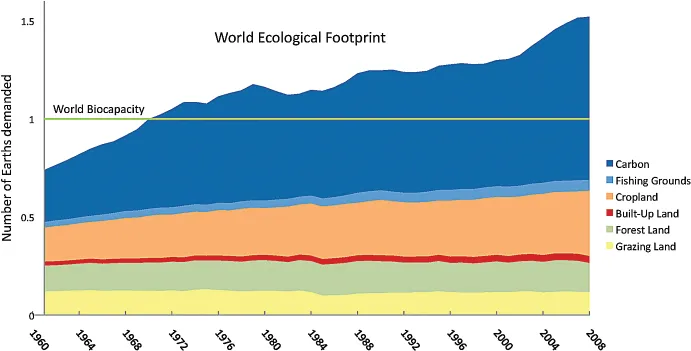

THE CASE FOR STEWARDSHIP

- 37 percent decline in temperate and topical freshwater ecosystems

- 24 percent decline of marine life

- percent decline in terrestrial plant and animal species

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- dedication

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- KEY SUSTAINABILITY INDICATORS

- PART 1: CONTEXT

- PART 2: ACTUALIZING THE VISION

- PART 3: SUSTAINABLE HEALTHCARE TODAY

- PART 4: VISIONING THE FUTURE

- Index

- Series Page

- End User License Agreement