![]()

Chapter 1

Development of Membrane Processes

K. Smith

1.1 Historical background

The ability of membranes to separate water from solutes has been known since 1748, when Abbé Nolet experimented with the movement of water through a semi-permeable membrane. Depending on the reference, either Abbé Nolet or Dutorchet coined the word osmosis to describe the process. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, membranes were used exclusively for laboratory applications, and often consisted of sausage casings made from animal intestines or the bladders of pigs, cattle or fish.

The first synthetic membranes were produced by Fick in 1855, and appear to have been made of nitrocellulose. Membranes based on cellulose were known as collodion and had the advantages of reproducible characteristics compared with the previously used animal-based membranes. Bechhold further advanced the process for manufacturing collodion membranes when he developed methods for controlling pore size and measuring pore diameters in 1907. He is generally credited with first using the term ultrafiltration (UF). In addition, Richard Zsigmondy at the University of Göttingen, Germany, patented a membrane filter in 1918 that was referred to as a cold ultrafilter. His work becomes the basis of the membrane filters produced by Sartorius GmbH.

Collodion membranes produced by the Sartorius GmgH of Germany became commercially available in 1927. The primary use of membranes until the 1940s was the removal of micro-organisms and particles from liquids and gases and research applications. There was a critical need to test drinking water in Europe for microbial content following the Second World War, and membranes were developed that could rapidly filter water and capture any micro-organisms on the membrane surface, where they could quickly be enumerated to determine the safety of the water for human consumption.

In addition to the separation of relatively large particles from water, there was interest in developing membranes that could desalinate sea or brackish water. The term reverse osmosis (RO) had been coined in 1931 when a patent was issued for desalting water; however, the available membranes could not withstand the pressures required.

Although many improvements were made in the following years, including the use of other polymers for constructing membranes, membranes were limited to laboratory and small specialised industrial applications. Factors limiting the use of membranes included a lack of reliability, being too slow, not sufficiently selective and cost.

A breakthrough came in the early 1960s when Sourirajan and Loeb developed a process for making high-flux, defect-free membranes capable of desalinating water. Researchers at the time believed the best approach to improving flux would be to reduce the thickness and thereby the resistance to flow of the membrane. Sourirajan and Loeb attempted to produce such membranes by taking existing cellulose acetate membranes and heating them while submersed in water in a process known as annealing. They expected the membrane pores would increase in size by such a process, but instead the pores became smaller and the membrane more dense. When they attempted the same process with cellulose acetate UF membranes, they discovered not only did the pores become smaller but the ability of the membrane to reject salt increased, as did flux. The flux improvement was such that the membranes could be a practical way to desalinate water.

The annealing process of Sourirajan and Loeb had created an anisotropic or asymmetric membrane. Anisotropic membranes have different behaviour depending on which side of the membrane is used for the separation. Although this type of membrane had been seen over 100 years earlier with natural membranes, it had not been reproduced with the synthetic variety.

The key to the anisotropic membrane of Sourirajan and Loeb was the thin ‘skin’ on one surface of the membrane. The skin typically was approximately 0.1–0.2 µm thick and had a dense structure whereas the remainder of the membrane had a very porous open structure. The thickness of the membrane essentially determined the flux and so by reducing the effective separating distance from 100–200 µm to 0.1–0.2 µm the rate of liquid crossing the membrane dramatically improved, but because of the small pores in the skin the rejection of salt remained high.

Many changes in the production of membranes occurred during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. By continuing the work of Sourirajan and Loeb, others were able to develop additional methods for producing membranes. Initial membrane modules were plate-and-frame (Danish Sugar Corporation) or hollow fibre (Amicon) designs, but membranes in formats, such as spiral-wound and tubular (Abcor), were introduced shortly afterwards. The thickness of the separating layer was further reduced to less than 0.1 µm. Large plants using RO, UF and microfiltration (MF) were operating around the world by 1980.

Cellulose acetate remained the material of choice until the mid-1970s, when methods of producing composite membranes for water desalination were developed. By combining polysulphone and polyamide, composite membranes had the advantage of high salt rejection combined with good water flux and increased resistance to temperature and chemicals. Nanofiltration (NF) or ‘loose RO’ membranes became available in the mid-1980s. The NF membranes operated at lower pressures than RO systems, and were able to permeate monovalent ions. They found immediate application in producing ultrapure water by permeating trace salts from water produced by RO.

In addition, membranes made from inorganic materials, such as zirconium and titanium dioxide, became commercially available in the mid-1980s. Membranes made from these materials are referred to as mineral or ceramic and are available in tubular form for UF and MF. Union Carbide (USA) and Societé de Fabrication d'Elements (France) used carbon tubes covered with zirconium oxide for their inorganic membranes. Later Ceravèr (France) used a ceramic base with aluminium oxide. Chemical and temperature resistance were the significant advantages of ceramic membranes. It was originally thought that such membranes had an unlimited life, but subsequent experience has shown this is not the case.

Advancements in membrane composition and design along with operation of membrane systems have continued. A wide variety of membrane polymers and designs have been adapted for RO, NF, UF and MF, resulting in many commercial applications. The feasibility of membrane-based applications depends chiefly on the ability of the filtration process to economically produce an acceptable product. Membrane pore size distribution, selectivity, operating conditions, membrane life, capital and operating costs become important economic considerations. These parameters are in turn influenced by many factors, such as the membrane polymer, element configuration and system design.

1.2 Basic principles of membrane separations

Membrane filtration is a pressure-driven separation process using semi-permeable membranes. The size of membrane pores and the pressure used indicate whether the term RO, NF, UF or MF is used for a given separation. RO and NF systems use the highest pressures and membranes with the smallest pores, whereas MF has the lowest operating pressures and membranes with the largest pores. UF is intermediate in pressure used and membrane pore size.

1.2.1 Depth versus screen filters

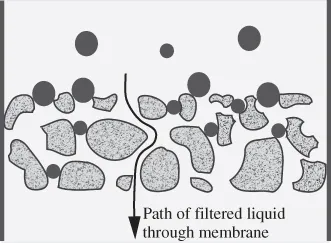

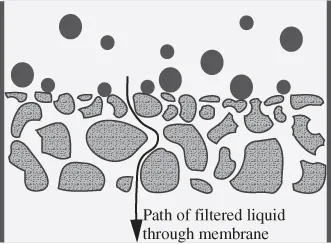

In the past, filtration processes relied on depth filters. This type of filter has fibres or beads in a mesh-like structure. Particles in the feed solution become trapped or adsorbed within the filter network, which eventually clogs the filter, thereby resulting in replacement of the filter (Fig. 1.1). By contrast, screen type filters generally rely on pores, with the size and shape of the pores determining passage of particles. Pores are more rigid and uniform and have a more narrowly defined size than mesh openings in a depth filter. Components not able to pass through pores remain on the membrane surface and, therefore, do not typically become trapped within the membrane structure (Fig. 1.2). Because the fouling materials remain on the surface, internal fouling decreases and the membrane can be reused.

1.2.2 Isotropic versus anisotropic membranes

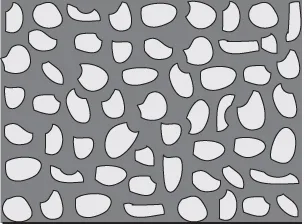

Membranes can have several types of internal structure. Terms, such as microporous, non-porous, isotropic and anisotropic, refer to the structure of the membrane. Typically, membranes are either isotropic or anisotropic. Microporous and non-porous refer to isotropic membrane structure. An isotropic membrane will have a relatively uniform structure (Fig. 1.3), i.e. the size of the pores is similar throughout the membrane. The membrane, therefore, does not have a top or bottom layer, rather the membrane properties are uniform in direction. Isotropic membranes generally act as depth filters and, therefore, retain particles within the internal structure resulting in plugging and reduced flux.

Microporous and non-porous membranes typically are isotropic. Microporous membrane structure can resemble a traditional filter; however, the microporous membrane has extremely small pores. Materials are rejected at the surface, trapped within the membrane or pass through pores unhindered, depending on particle size and size of the pores. A non-porous membrane will not have visible pores and materials move by diffusion through the membrane.

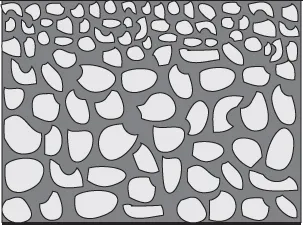

An anisotropic or asymmetric membrane has pores that differ in size depending on their location within the membrane (Fig. 1.4). Typically, anisotropic membranes will have a thin, dense skin supported by a thicker and a more porous substructure layer. The thin top layer provides high selectivity, whereas the porous bottom layer has good flux. Membranes used for commercial separations in the food industry are typically anisotropic.

1.2.3 Cross-flow filtration

RO, NF, UF and MF systems all involve cross-flow filtration, which can be compared to the traditional method of perpendicular filtration. In traditional filtration (Fig. 1.5), the entire ...