![]()

PART ONE

Foundations

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Human World

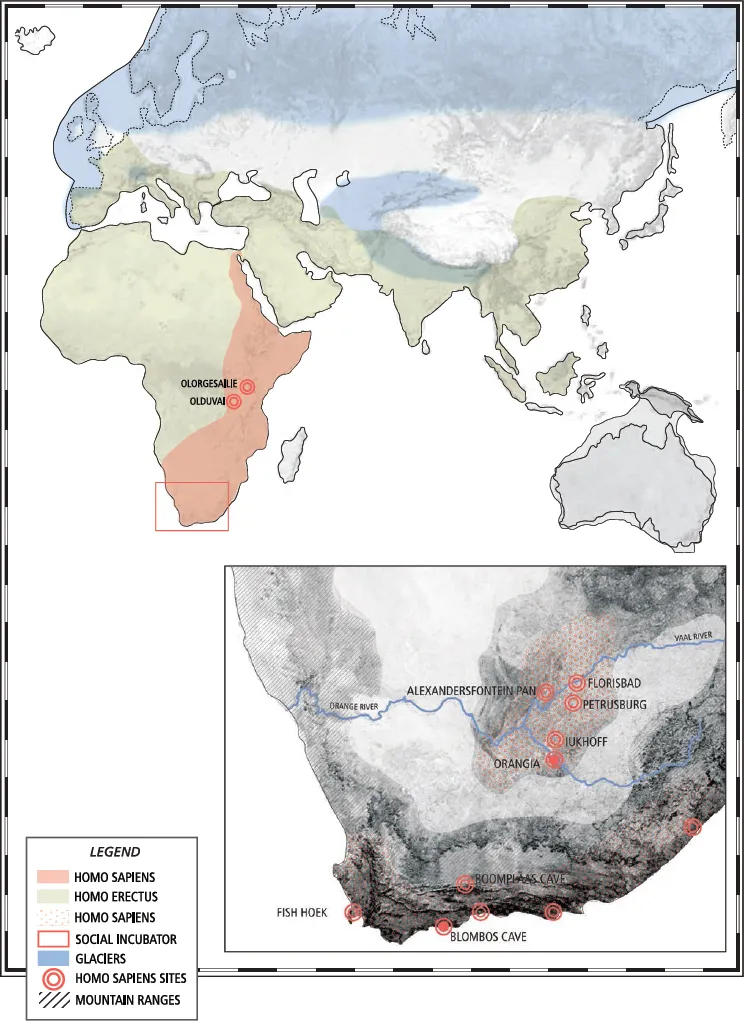

Some ninety thousand years ago, our ancestors—optimistically labeled Homo sapiens—began to migrate out of Africa. Their movement was incremental so it would hardly have dawned on them how momentous the consequences of their action were to be. But Homo sapiens were not the first to have set forth. Homo erectus had left Africa some 1.8 million years earlier and over the course of time had spread as far as China and England (Figure 1.1). Although these early hominoids are often portrayed as less advanced than Homo sapiens, it is now clear that they laid the foundations for later developments.1 Tangible evidence is hard to come by, apart from one clear example, a unique type of hand axe that was to remain an essential and effective part of human life for hundreds of thousands of years.2 First a proper stone—usually a river cobble of basalt or quartzite or flint—had to be chosen and then it had to be hit in a particular way with the help of another stone to flake off pieces. The stone had to be flipped and rotated with different types of strikes producing different edges. The final result was an oval or triangular object, pointed on one end and rounded at the base to conform to the shape of the palm where it was held. The symmetrical design of these axes makes them stand out from earlier stone tools; the symmetry also clearly reflects the quantum leap in the cognitive and linguistic capacities that make all of us human. Furthermore, tool making was no longer an informal process but became something of an industry, with some place—and obviously also craftsmen—dedicated solely to their production (Figure 1.2). People also worked in unison at kill sites, as evidenced at Olorgesailie, Kenya, where, along the shore of a large, now extinct isolated lake, thousands of stone tools have been found

The axes were mostly used for carving meat or breaking bones to access marrow.3 But experiments have also shown that they might have been thrown discus-style. With a range of about 30 meters, the point hurtles earthward with tremendous force. Such weapons would not have been good for moving targets, but against stationary ones, like animals standing close to each other while drinking at a lake’s edge, they would have been ideal, which perhaps explains why axes like these seem so often to be found in riverbeds and along lake shores.4 In one site in England, near a watering hole, a hand axe was found still lodged in the skull of a mammoth. Despite the assumption that making weapons was the key factor in this evolutionary moment, it is not necessarily obvious that these were always weapons. Some are so well-crafted and made from unusually colored stones that they might have been used as a marker of ancestral status associated with ritual activity. This seems very much to be the case of a particularly well-made stone axe uncovered at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, at a site near the shores of a one-time lake (Figure 1.3). Dating to about 1.8 million years ago, it is 23 cm long and was fashioned from a shiny, gray green volcanic rock. Olduvai Gorge produced another surprise, a circle of lava stones that were the remains of a hut or windbreaker consisting of branches anchored at the base by stones piled into heaps and spaced on the circumference about every .7 meters. This is the earliest evidence so far of a man-made structure.5 Scattered around the hut are the remnants of stone chipping and other activities

The Olduvai Gorge settlement proves without a doubt that a social order and spatial differentiation had developed during the time of Homo erectus. What is also clear is that people could expand and replicate their culture across space and time and, indeed, in a variety of ecological zones. In India, where Homo erectus arrived around 700,000 BCE, they lived in the semi-arid regions of western Rajasthan, in the alluvial plains of Gujarat, even in the moist deciduous woodlands in central India. The Baichbal and Hunsgi Valleys, located in the Deccan region of India, were particularly rich in settlements. In the wet season, groups would have dispersed over the valley in search of plant foods, berries, and fruits, whereas in the dry season, they congregated in larger groups near the numerous spring-fed streams, and focused more on the hunt, leaving behind their tell-tale axes. The bones of wild boar, cattle, elephant, horse, and hippopotamus that archaeologists have found at these sites indicate that people hunted in both forests and open grasslands. The Acheulean axe made it to England by around 500,000 BCE if not earlier, with sites at Barnfield Pit and Boxgrove Quarry.6

While this colonization of the globe was taking place, a genetic mutation occurred back in Africa, giving rise to the fabled Homo sapiens, who, though of smaller build, had a brain that allowed them to intensify and broaden the incipient social, technical, and territorial accomplishments of Homo erectus. Stone tools became more complex and differentiated. The heavy hand axe gave way to slender points that were attached to sticks to form spears, allowing hunters to attack more dangerous prey. By 130,000 BCE, groups were exchanging materials over large distances and creating a network of relations that by necessity must have been based on mutually advantageous social bonds.

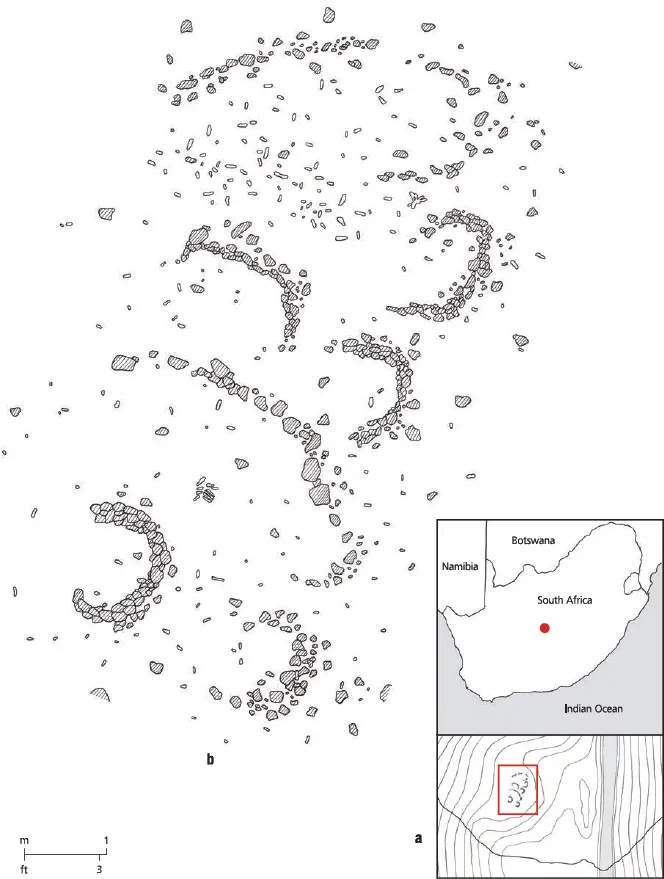

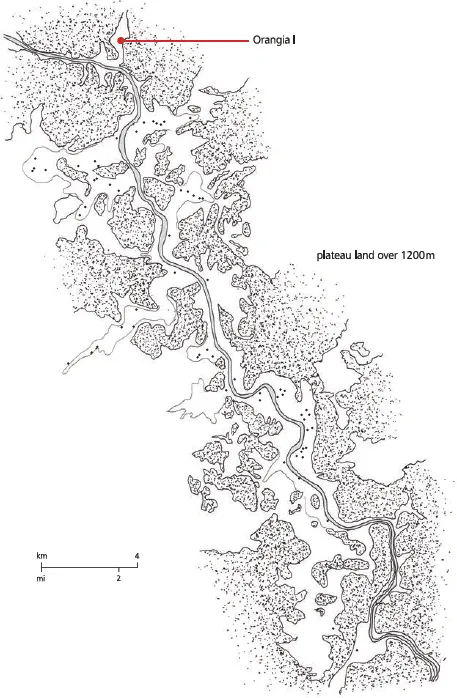

The development of this distinctive culture took place in southern Africa in two regions, one in north central South Africa and the other to the south along the shore. The first was an area of savannah punctuated by lakes, for though the time period was colder than today, it was also wetter Alexandersfontein Pan in South Africa was in its heyday a typical site. What is now a dried-out watering hole was a hundred thousand years ago a large lake, 9 kilometers across and 20 meters deep. The shores and the rivers feeding it were home to numerous camps where humans lived and thrived for thousands of years.7 Alexandersfontein Pan was hardly alone; it was, in fact, at the center of a large lake district, some 200 kilometers across, the sandy lake bed vestiges of which are still clearly imprinted in the landscape. Draining into the Orangia River at its southern end, it would have been ideal for humans with its extensive array of grasslands and wetlands, with animal herds ranging in between. Rocky outcrops provided a plentiful supply of lithic material. A camp near Florisbad next to a spring was where groups met to hunt and butcher animals.8 At a camp known archaeologically as Orangia I, people made C-shaped wind shelters similar to those made by the Aboriginal Australians. (Figure 1.4a, 1.4b) Orangia 1 was located on the bluff overlooking a river tributary to the Orange River. With a cliff behind it, the site was probably only accessed from the river itself, and was probably used during the dry season. The remnants of such camps dot a hundred-kilometer stretch of the Orange River, along its shores and lower bluffs, and even though not all the camps that have been found by archaeologists were used at the same time, the river with its protected canyons was clearly a magnet for human activity.9 (Figure 1.5)

Equally important to the emergence of Homo sapiens culture was the thousand-mile stretch of shores and cliffs that overlook the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean around Africa’s southern tip. The oceans would have been lower back then, allowing the cave dwellers to gaze out over a kilometer or so of salt marshes. At the caves at Pinnacle Point, Blombos, and at the mouth of Klasies River, people began to fish around 140,000 BCE, and around 70,000 BCE they began to use bone tools instead of stone tools to hunt dune mole rats and seals. (Figure 1.6) The caves were not temporary shelters, but home bases used seasonally and perhaps even the whole year around. They were inhabited in this way for thousands of years at a stretch.

BLOMBOS CAVE

Though Blombos Cave with its tools, fishhooks, scrapers, and hand axes gives us invaluable insight into the food acquisition of our early ancestors, what surprised archaeologists in particular was the discovery of a set of small mollusk shells that was part of a necklace, with each shell carefully drilled with a hole for the string10 (Figure 1.7). We have no way of knowing how the necklace was used, but it was not to adorn a pretty neck. For the Zulu today, beaded necklaces convey information about a person’s marital status, economic level, and origin.11 For the Paiwan, who live in Taiwan, necklaces are imbued with living spirits and are carefully passed down among the chieftains from generation to generation. The necklace serves as a sign of status, a marker of historical events, and the embodiment of powerful spirits. Implications of this sort must already have been present at Blombos Cave.

The ochre found in many of the South African sites is further proof of social complexity. (Figure 1.8) Hundreds of small chunks of it were found in Blombos Cave. Some pieces were in the shape of crayons that were presumably used to paint their bodies or make images on the walls. Known scientifically as he...