Fundamentals of Light Microscopy and Electronic Imaging

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Fundamentals of Light Microscopy and Electronic Imaging

About this book

Fundamentals of Light Microscopy and Electronic Imaging, Second Edition provides a coherent introduction to the principles and applications of the integrated optical microscope system, covering both theoretical and practical considerations. It expands and updates discussions of multi-spectral imaging, intensified digital cameras, signal colocalization, and uses of objectives, and offers guidance in the selection of microscopes and electronic cameras, as well as appropriate auxiliary optical systems and fluorescent tags. The book is divided into three sections covering optical principles in diffraction and image formation, basic modes of light microscopy, and components of modern electronic imaging systems and image processing operations. Each chapter introduces relevant theory, followed by descriptions of instrument alignment and image interpretation. This revision includes new chapters on live cell imaging, measurement of protein dynamics, deconvolution microscopy, and interference microscopy.

PowerPoint slides of the figures as well as other supplementary materials for instructors are available at a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/murphy/lightmicroscopy

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

OVERVIEW

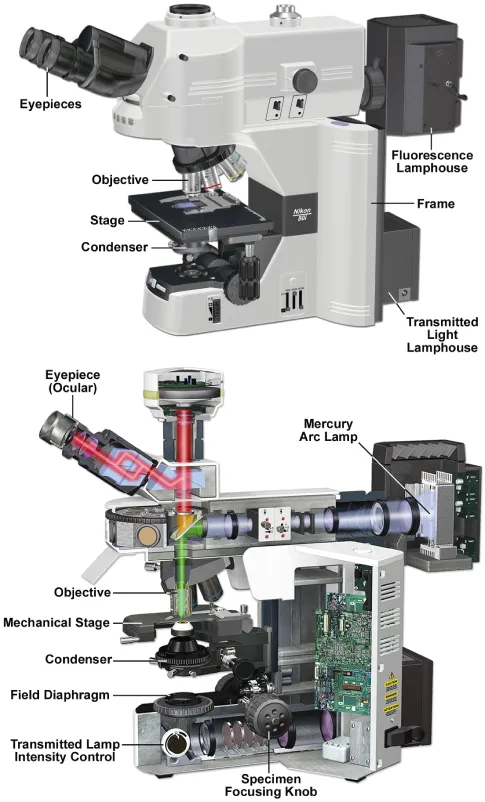

OPTICAL COMPONENTS OF THE LIGHT MICROSCOPE

The research light microscope with upright stand. Two lamps provide transmitted and reflected light illumination. Note the locations of the knobs for the specimen and condenser lens focus adjustments. Also note the positions of two variable iris diaphragms: the field diaphragm near the illuminator, and the condenser diaphragm at the front aperture of the condenser. Each has an optimum setting in a properly adjusted microscope. Above: Nikon Eclipse 80i upright microscope; below: Olympus BX71 upright microscope.

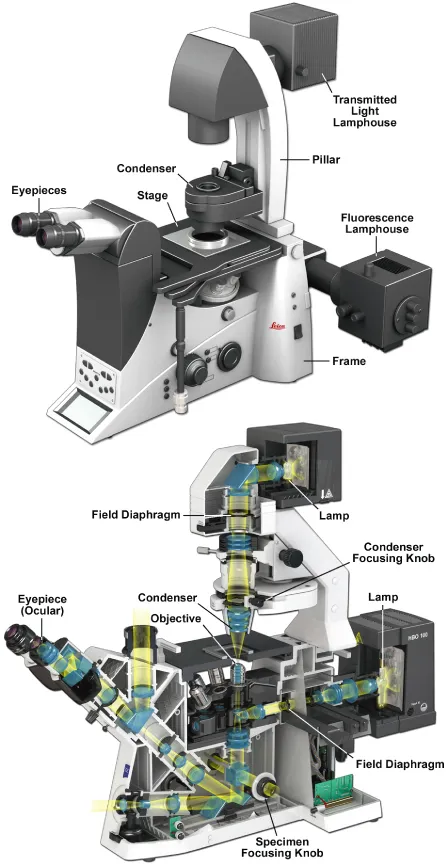

The research light microscope with inverted stand. As in upright designs, two lamps provide transmitted and reflected light illumination. Note the locations of the knobs for the specimen and condenser lens focus adjustments, which are often in different locations on inverted microscopes. Also note the positions of two variable iris diaphragms: the field diaphragm near the illuminator, and the condenser diaphragm at the front aperture of the condenser. Each has an optimum setting in a properly adjusted microscope. Above: Leica Microsystems DMI6000 B inverted microscope; below: Zeiss Axio Observer inverted microscope.

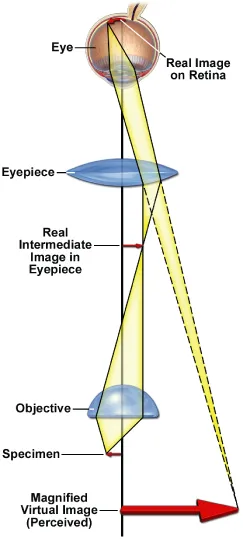

Perception of a magnified virtual image of a specimen in the microscope. The objective forms a magnified image of the object (called the real intermediate image) in the eyepiece; the intermediate image is examined by the eyepiece and eye, which together form a real image on the retina. Because of the perspective, the retina and brain interpret the scene as a magnified virtual image about 25 cm in front of the eye.

APERTURE AND IMAGE PLANES IN A FOCUSED, ADJUSTED MICROSCOPE

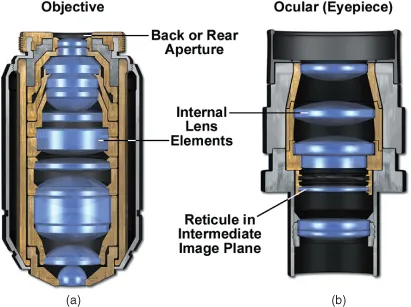

Objective and eyepiece diagrams. (a) Cross section of an objective showing the location of the back or rear aperture. (b) Cross sectional view of a focusable eyepiece, showing the location of the real intermediate image, in this case, containing an eyepiece reticule. Notice the many lens elements that make up these basic optics.

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER 1 FUNDAMENTALS OF LIGHT MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 2 LIGHT AND COLOR

- CHAPTER 3 ILLUMINATORS, FILTERS, AND THE ISOLATION OF SPECIFIC WAVELENGTHS

- CHAPTER 4 LENSES AND GEOMETRICAL OPTICS

- CHAPTER 5 DIFFRACTION AND INTERFERENCE IN IMAGE FORMATION

- CHAPTER 6 DIFFRACTION AND SPATIAL RESOLUTION

- CHAPTER 7 PHASE CONTRAST MICROSCOPY AND DARKFIELD MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 8 PROPERTIES OF POLARIZED LIGHT

- CHAPTER 9 POLARIZATION MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 10 DIFFERENTIAL INTERFERENCE CONTRAST MICROSCOPY AND MODULATION CONTRAST MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 11 FLUORESCENCE MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 12 FLUORESCENCE IMAGING OF DYNAMIC MOLECULAR PROCESSES

- CHAPTER 13 CONFOCAL LASER SCANNING MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 14 TWO-PHOTON EXCITATION FLUORESCENCE MICROSCOPY

- CHAPTER 15 SUPERRESOLUTION IMAGING

- CHAPTER 16 IMAGING LIVING CELLS WITH THE MICROSCOPE

- CHAPTER 17 FUNDAMENTALS OF DIGITAL IMAGING

- CHAPTER 18 DIGITAL IMAGE PROCESSING

- APPENDIX A: ANSWER KEY TO EXERCISES

- APPENDIX B: MATERIALS FOR DEMONSTRATIONS AND EXERCISES

- APPENDIX C: SOURCES OF MATERIALS FOR DEMONSTRATIONS AND EXERCISES

- GLOSSARY

- MICROSCOPY WEB RESOURCES

- RECOMMENDED READING

- REFERENCES

- INDEX