![]()

SECTION II

STRATEGIES FOR PROGRESS MAKERS

![]()

9

ENVISION THE FUTURE WITH CALCULATED BOLDNESS

To try to be safe everywhere is to be strong nowhere.

—Sir Winston Churchill

When words such as boldness, courage, and bravery crop up in a conversation, often the stories involve military commanders, officers, and troops. Daring exploits against daunting odds usually provide the main storyline. Yet, the storytellers often neglect to mention an essential feature of most bold action—namely, calculation, which helps to minimize risk. In this chapter, we want to examine how progress makers act with both calculation and boldness. Clearly, there are times that too much calculation can lead to inaction (e.g., analysis paralysis). But progress makers rarely fall into that trap. In fact, progress makers see calculation as strengthening boldness.

So it seems fitting to start this chapter by examining how one of the toughest military units dealt with a largely administrative conundrum. In particular, let’s study how the U.S. Navy SEALs (Sea, Air, & Land) approached the task of adding an additional 500 men to its ranks of 2,300 active servicemen. That might not seem like a daunting task until you take into account some important facts:

- Fact 1: Navy SEALs are considered one of the most elite warriors in the world. They are tasked with the sensitive and difficult military missions like locating high-ranking Al Qaeda terrorists in the rugged mountains of Afghanistan.1

- Fact 2: They have plenty of applicants, but most can’t make it through the grueling training process. Only one in four candidates survives BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training).2

- Fact 3: Compromising on quality is not an option.

Captain Duncan Smith dug into the data and discovered that triathletes were graduating from the program at over a 40% rate compared to others who graduated at a rate around 26%.3 He decided to directly influence the system by altering the traditional recruitment methods that relied on the Navy sending the SEALs recruits. Captain Smith and his crew refocused the advertising and began to target athletes attending endurance events such as major triathlons and the Winter X Games. The strategy reaped benefits, as the graduation rates steadily climbed.4

Captain Smith demonstrates how progress makers think and behave. Elite warriors, like special leaders, know that shooting the target is easier than locating the target. Progress makers zero in on the issues that need the most attention and then vigorously attack them. In a nutshell, that’s envisioning with calculated boldness.

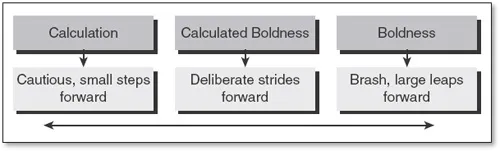

DEFINING THE CONCEPT

The synonyms for calculation and boldness clash. Calculating leaders act with deliberation, design, and planning. Bold leaders act with audacity, courage, and daring. Overly calculating leaders hesitantly budge their organizations forward. Overly bold leaders impetuously jump to a new direction. Progress makers seek out the sweet spot between the overly timid and overtly brash (see Figure 9.1). They find the synergy between the two extremes by acting boldly when the right conditions prevail. They attack like cyclist Lance Armstrong does on the mountain stages of the Tour de France. He doesn’t attack, attack, attack. He realizes that this supreme athletic challenge is a “chess game” driven by simple truth: “It’s easier to ride just behind someone than in front. A lot easier: At twenty-five miles per hour on the flats, the trailing rider uses 30 percent less power than the leader.”5 Consequently, he calculates the optimum time to stage an attack by sensing potentially decisive vulnerabilities of an opponent. Then he attacks with an astonishing degree of vigor and aggressiveness.6 That’s what it takes to win the yellow jersey of the Tour de France seven times.

Figure 9.1 Calculated Boldness Continuum

Likewise, progress makers envision the future with calculated boldness by ascertaining the most timely and significant points of intervention. Why? BECAUSE THOSE IN LEADERSHIP POSITIONS WHO PUT A BOLD FACE ON EVERYTHING WIND UP EMPHASIZING NOTHING. Everything appears to be a top priority. And if the leaders will not make a choice, then the followers will choose whatever they wish as a priority. The intervention point may be refining a platform or creating a new one. Regardless, after progress makers make the determination, they forcefully and unrelentingly pursue their aims. In short, they shun both timidity and brashness.

Shun Timidity

Progress makers shun timidity by silencing their fears with three abiding convictions. First, they know that success is always temporary. Decline, growth, and change are inevitabilities that progress makers neither resist nor bemoan; rather, they embrace these inescapable realities with an eye toward the future. Second, they know that strategic opportunities are rare. Better to seize them than let them pass. For example, during recessions, companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Genentech, and Google jumped on opportunities to acquire strategic assets and buy small firms that propelled their growth for years.7 Third, they know that sometimes you just have to ignore the economic headwinds and create your own opportunities. Such were the sentiments of the founders of CNN, Microsoft, and FedEx who started their companies during perilous economic times.8 In fact, a Kaufmann Foundation study found that “well-over half of the companies on the 2009 Fortune 500 list, and just under half of the 2008 Inc. list began during a recession or bear market.”9

Shun Brashness

Progress makers tend to be restless and can have a natural brashness. Yet, they temper these impulses with calculation. At the most basic level, calculation involves a thoughtful analysis of relative benefits and costs of a particular move. Calculations can be done on a paper napkin in the heat of battle as well as on a pristine sheet of flipchart paper in the friendly warmth of an executive retreat. For the progress maker, situational constraints matter little. Situational comforts matter less. Situational sensitivity, though, dominates all. Why? It allows the progress maker to envision thoughtfully WHAT issues to attack and WHEN to boldly move forward.

Calculated boldness does not materialize out of some inner feeling of power or omnipotence. You don’t have to don Superman’s cape to act with calculated boldness. In fact, feelings of anxiety and fear take a backseat to the cerebral activity of making a calculated determination of the odds of success. For the progress maker, bold thoughts precede action; the emotions will follow the mind’s lead. It sounds simple in theory. In practice it is not. Why? Read on.

WHAT INHIBITS CALCULATED BOLDNESS?

Clearly, the timid and simple-minded cannot act with calculated boldness. But let’s put those types of leaders aside for now. Instead, let’s focus on those leaders who have the potential to become progress makers. There are often manageable issues that stand in the way of a leader’s potential. We discuss three of the major ones in this section.

First, the Leader Overly Relies on Familiar Courses of Action

The “Law of the Hammer” declares that if you give child a hammer, she will start to see a lot of things that need hammering—even things that don’t. People misuse and overuse tools all the time. Students, for example, routinely overuse the Internet for research. They often fail to take into account the credibility of the Web site, the motives of the content provider, and the bias of search engines. Moreover, they often fail to realize that some of the most valuable content lies outside the realm of the Internet in the aisles of the library and the in minds of experts. If you were to ask typical college students about problems with credibility, motives, and search biases, they would often say the right things. Unfortunately, many do not behave with those issues clearly in mind.10 Why? Expediency and familiarity. In colloquial terms, it equates to the sentiment, “I’ve always done it that way before. Why change?” Consequently, inertia—rather than reason—sets organizational direction.

Let’s turn to the sciences for a deeper perspective on inertia. It was Galileo Galilei who first advanced the principle of inertia that Isaac Newton eventually codified in his first law of thermodynamics. In the simplest terms, it means “a body in motion tends to remain in motion, a body at rest tends to remain at rest.”11 Translating the law from the physical to the organizational sciences proves revealing and enlightening, for the same law of inertia can apply to almost any organizational practice. Once certain processes or procedures are set in motion, they prove difficult to stop regardless of how dys-functional they may actually be to organizational health. How else do we explain the seemingly mindless perpetuation of government subsidies to underperforming agencies and obsolete industries? Fighting against the forces of inertia may prove to be one of the most difficult battles that aspiring progress makers wage.12

Of course, few people hasten to defend “organizational inertia.” More often, the progress maker encounters resistance couched in terms of “respect for tradition.” One progress maker, Winston Churchill, growled a classic retort when faced with this type of resistance. Early in his career, he served as First Lord of the Admiralty. Unlike other government bureaucrats, he started pushing for major reforms. Near the end of a conference with his admirals, he was accused of “impugning the traditions of the Royal Navy.”13 His response: “‘And what are they?’ asked Winston. ‘I shall tell you in three words. Rum, sodomy, and the lash. Good morning, gentleman.’”14

Second, the Leader Lacks Awareness of All the Potential Points of Intervention

Imagine trying to develop a medical treatment for polio with no knowledge of viruses. Even Jonas Salk couldn’t do that. Fortunately, he knew a great deal about diseases that occurred on the viral level and developed a vaccine that saved millions of lives. Likewise, how can leaders inspire progress without knowledge of the various levels at play in their organizations? They cannot.

Symptoms often appear at one level that are not the real source of the problem. Polio victims, for instance, can display symptoms of the malady on a variety of levels, including headaches (vascular or neurological level), nausea (gastrointestinal level), and, in some cases, paralysis (muscular level). But the disease cannot be effectively prevented or effectively treated at any of these levels.15 Likewise, poor employee performance may be induced by inappropriate incentives, improper hiring practices, incompatible coworkers, or any number of other issues. Without an awareness of these levels, leaders may respond inappropriately to the situation.

The notion of levels implies nesting or layering. Planets nest within planetary systems, which nest within galaxies, which in turn comprise our universe. You can see a similar layering as we move between subatomic particles, atomic particles, atoms, molecules, and so on. Clearly, the idea of levels burrows deeply into our ways of thinking about the ...