![]()

Section II

A New Way Forward

![]()

6

Time to Flip the Funnel

In Chapter 1, I described how the traditional marketing funnel is anything from outdated to flat-out broken, and I introduced several key themes and terms that traditionally have been absent from strategic planning and agenda-setting in the board room: retention, attrition, churn, and technology as a numerator.

ONE SOLUTION: EXTEND THE FUNNEL

In this day and age of the Long Tail, we’d almost expect a rather long trickle of a tail to stem from the end of the funnel. But even if this were the case, it wouldn’t substantially address any of the shortcomings mentioned in Chapter 1, at least not in the kind of way that could have the potential theoretical impact of halving your budget, while simultaneously doubling your revenue. With this theory, the funnel would just get narrower and narrower and represent one or both of two extremely undesirable scenarios: less investment against fewer and fewer customers, with no guarantee of positive (versus negative) outcome. Granted, there’s value in acknowledging that something should happen after the moment of truth—that is, the purchase—but what? Is it customer relationship management (CRM). Loyalty marketing? One-to-one marketing? All three? Or something completely different?

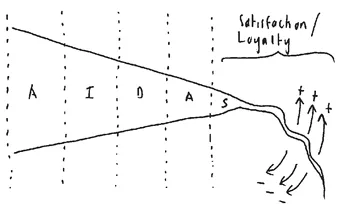

The goal is not simply to extend the goodness; it’s to enhance the value, impact, meaning, and purposes associated with customer loyalty and experience. As the doodle in Figure 6.1 illustrates, perpetuating a purchase without necessarily improving on it is just as likely to lead to a negative result as to a positive one.

Figure 6.1 The Long Tail of A.I.D.A.

Source: © Joseph Jaffe.

ANOTHER SOLUTION: TURNING IT ON ITS SIDE

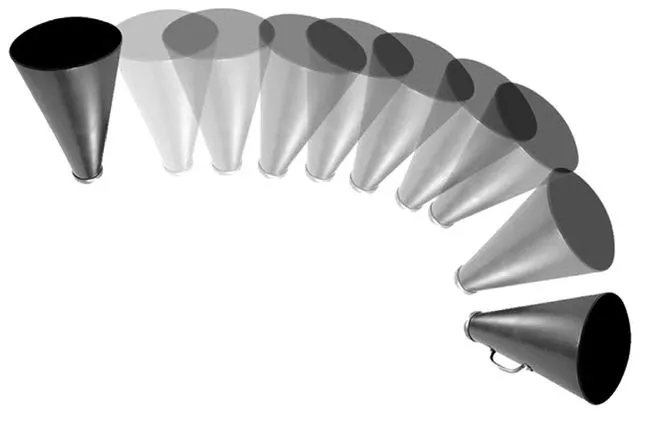

In Seth Godin’s e-book Flipping the Funnel, the author makes the great point that your customers are essentially underused “assets.” Given that practically every company has more customers than salespeople, isn’t it logical that customers should have an amplifier or a megaphone (hence the funnel flipped on its side in Figure 6.2)?

Godin astutely notes that former customers or those with grievances already use certain channels—predominantly the Web—as an amplifier. It’s thus incumbent on us to make sure our fans or friends have the same opportunity. Let’s call it equal opportunity for customers.

I’m certainly not criticizing the idea of turning the funnel on its side—except for the fact it’s really comparing apples with carrots insofar as it’s a smart, lateral, and even literal interpretation of a theoretical concept. It also represents a part of the solution to the multitude of problems associated with the traditional funnel (namely, an unhealthy obsession on an acquisition-led process that is neither efficient nor effective).

ANOTHER SOLUTION: FLIPPING IT COMPLETELY

Why not turn the funnel on its head? Instead of ending with your customers, why not begin with your lifeblood, the single biggest—if not the only—reason you’re in business today?

Figure 6.2 The Funnel Becomes the Megaphone

Source: Seth Godin. Reprinted by permission.

We need not abandon the customer acquisition process or minimize the role that awareness and/or action play in terms of moving prospective customers from unawareness to paying customers. The same could be said for my championing of new media over old, or conversation over communication—one does not necessarily replace its predecessor or counterpart. However, it does bring with it new and differentiating thinking. From the standpoint of investing in both human and financial resources, it also reprioritizes strategic thinking and mind-share from an otherwise saturated space to one that essentially represents virgin territory in terms of upside, potential, and impact. It’s also an acknowledgment that the proposed space in question is significantly evolved:

• The sharp and clinical scalpel of digital trumps the blunt hatchet of advertising.

• The fluid and pervasive conversation washes away the unidirectional current of communication.

• The meaningful and long-lasting commitment of retention deeply resonates over the superficial and materialistic attraction of acquisition.

I am saying that there is a better way. There just has to be. And if we’re able to elevate retention (customer service, dialogue, and customer outreach or affiliate 2.0) to the point at which it becomes a strategic imperative at the expense of the traditional acquisition efforts from an optimization and budget allocation standpoint . . . then maybe, just maybe, we’ll be able to change the way we do business for the better. Forever.

On one hand, this represents starting with your customers, and if there’s time, effort, energy, and budget remaining, hop on over to the pool of uninitiated prospects. On the other, it speaks to repairing the holes in the net to assure that you’ll enjoy more fruitful results the next time you go fishing.

There should always be room for both acquisition and retention. Why can’t the respective potentials of both be achieved simultaneously? Why does it have be a zero-sum game? Or what about the really radical thought that we might never NEED to invest in acquisition again if we’re able to deliver effectively on retention?

When I was Down Under in Australia—the perfect place to be flipping anything on its head—I proposed this thought to one of the nation’s largest banks when they told me that they “didn’t really need” any new customers (they had enough). What if you announced that you would not be taking new customer accounts or applications (at least for a period of time)? What message would that send to your existing customer base -- and to those who weren’t yet part of your family in terms of aspiration, motivation, and desire? Would it make them want you more or less?

Radical thinking aside, any changes you make to your existing methodology and process—however small—will have major organizational implications when it comes to budget allocation, prioritization of objectives, time, and initiatives. That doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing—on the contrary. But your decision will ultimately depend on the company’s tolerance for risk (usually low) and its fervent belief in the power of its customer base—in terms of both staying and buying power. Regardless of whether you flip the funnel on its head in one decisive motion or experiment with tilting it just a few degrees, I hope you’ll acknowledge that the hypothesis on offer is a shift of the very foundation of marketing management as it relates to consumer behavior. At the very least, it’s an enhancement on existing theory and best practices; at the most, a complete and utter rethink.

Ultimately, where it fits and how far you take it is up to you, but I hope you’ll give this serious thought in terms of making permanent changes that permeate your organization. Of course, I believe that this could be the x factor for which you’ve been searching so hard. It certainly is not going to come from a new advertising campaign or manifest itself in an obtuse new web site, either.

THE DEATH OF LOYALTY

Before we get into the flipped-funnel methodology, it’s important to tackle—and possibly debunk—one of the most misused and even abused words in the marketing lexicon: loyalty. It’s a word that is liberally thrown around to refer to customers. It’s wholly interchangeable with a random impersonal e-mail that doesn’t even mention the customer by name, an indulgent and overpriced techmology (hat tip to Ali G) and database solution, or a frequent-purchase program that penalizes returning customers at every turn, such that they are helpless to use their miles or points with any reasonable ease. All of this drives them to the point at which they end up expiring, along with the customer’s tenure and so-called loyalty. Talk about a vicious circle!

It’s time for renewed thinking on loyalty. It’s best to begin with a clean slate—one without any sacred cows, predisposed thinking, or incumbent assumptions.

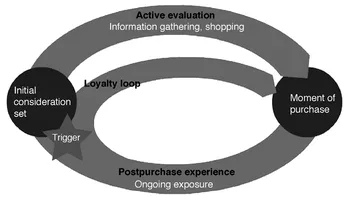

Consulting firm McKinsey & Company offers thinking on the customer journey, and seems to have blended the acquisition and retention processes together as fluid and circular. McKinsey segments loyalty into active and passive, as in “I’ll never purchase any product other than yours” versus “I’m open to purchasing yours in the future, and I’m equally open to purchasing other, similar products as well,” respectively.

The diagram of McKinsey’s consumer-decision-journey theory in

Figure 6.3 sheds some light on four current market truisms when it comes to loyalty:

1. Loyalty today is predominantly passive rather than active.

2. Companies mistake or confuse passive loyalty with active loyalty.

3. Companies need to segment loyalty in to several more meaningful categories.

4. Companies generally approach loyalty (programs such as CRM and the like) as equally or commensurately passive, that is, noncommittal, indecisive or lacking a clear and firm position.

Figure 6.3 The Consumer Decision Journey

Source: Exhibit 2 from “The consumer decision journey,” June 2009, The McKinsey Quarterly, www.mckinseyquarterly.com. Copyright © 2009 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

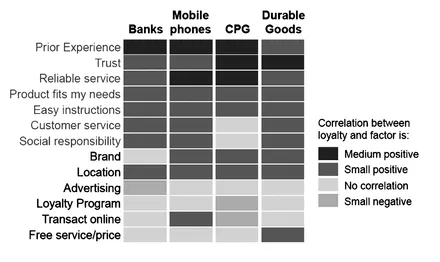

Case in point: According to research from Forrester (see Figure 6.4),14 loyalty programs have virtually zero—and in some cases, negative—correlation with loyalty in the banking, mobile phone, CPG (consumer packaged goods), and durable goods sectors. By contrast, prior experience, trust, and reliable service—in other words, consistency—had the closest correlation with loyalty.

It’s time to address the elephant in the room when it comes to loyalty.

THAT ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM IS YOUR CUSTOMER

Although they may not segment loyalty per se, most businesses today (sadly) do divide their customers into three very distinct categories, all of which exist within the animal kingdom: Lemmings (the hapless victims to mass-media hype and pop-culture indoctrination), Dogs (playful and loyal to a fault), and Goldfish (inherently forgetful). In reality, customers today are more like Chameleons (adaptive, unpredictable, ever changing, and contextually original), Dolphins (highly intelligent), and Elephants (terrific memory!). Besides their reputation for possessing incredible memory, elephants are also known as highly social animals who engage in greeting ceremonies, complex communication, courtship, teaching, and communal care.15 They’re also an endangered species—hunted and targeted as they simultaneously fight to adapt to shifting terrains and landscapes. Sounds kind of like how we treat and what we do with our customers, right?

Figure 6.4 Loyalty Programs and Loyalty Are Not One and the Same

Source: Forrester Research Inc.

If we want to show our customers that their purchase is just the beginning of a long and mutually beneficial exchange, then we need to think of them more as dynamic chameleons, engaged dolphins and mighty elephants. Look up to them. Acknowledge their presence. Stroke their egos. Feed them. Nourish them. Cool them off. And for heaven’s sake, get out of the way if they go on a rampage.

ENTHUSIASTS VERSUS INFLUENCERS

And as long as we’re rethinking the notion of loyalty, it’s probably also a good idea to do the same with the word “customer” itself. Who exactly is a—or specifically, our—customer? Is it someone who pays money or attention; consumes our products or services; or simply one who uses our intellectual property or brand equity?

Figure 6.5 Three Types of Premium “Customers”

Source: © Joseph Jaffe.

We do a fairly satisfactory job of segmenting our prospects in the marketplace; but how do or should we segment our customers—both direct (compensation) and indirect (attention)?

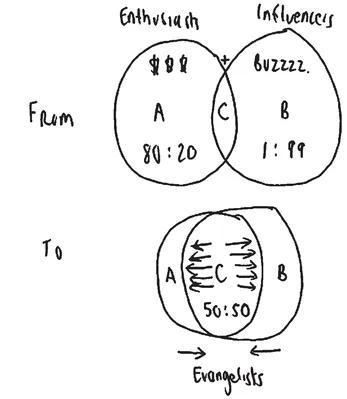

Figure 6.5 above offers a breakdown of three types of premium customers:

1. The 80:20 rule: The prototypical 20 percent of customers responsible for 80 percent of revenue

2. The 99:1 rule: The 1 percent of influences, iReporters,16 or content creators responsible for 99 percent of our buzz

3. The sweet spot: customers who both talk about and purchase from the brand

Using this segmentation, several key implications emerge:

1. Companies should utilize and deploy three distinct approaches when it comes to engaging walkers, talkers, and a hybrid of the two.

2. Companies should distinguish and differentiate between enthusiast and influencer behavior.

3. There’s no black and white, but rather 256 shades of gray. Although there are generalizations, customers exhibit both enthusiast and influencer behaviors. Companies should therefore treat their customers as influencers (the I in the flipped funnel) . . .

4. . . . and at the same ti...