eBook - ePub

Alexander the Great

A New History

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alexander the Great

A New History

About this book

Alexander the Great: A New History combines traditional scholarship with contemporary research to offer an innovative treatment of one of history's most famous figures.

- Written by leading experts in the field

- Looks at a wide range of diverse topics including Alexander's religious views, his entourage during his campaign East, his sexuality, the influence of his legacy, and his representations in art and cinema

- Discusses Alexander's influence, from his impact on his contemporaries to his portrayals in recent Hollywood films

- A highly informed and enjoyable resource for students and interested general readers

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alexander the Great by Waldemar Heckel, Lawrence A. Tritle, Waldemar Heckel,Lawrence A. Tritle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia dell'antica Grecia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Macedonian Background

“No Alexander if not for Philip” is true in more than just biological terms. Alexander’s triumphant conquests would not have been possible without Philip’s achievements, namely, the enormous expansion and consolidation of the Macedonian kingdom, with the removal of any danger posed by the Greek states or neighboring barbarians, and the development of an army ready to strike and a capable and loyal officer corps.1 But Philip did not create Macedonia from nothing, despite what ancient authors and modern scholars suggest: he inherited a kingdom which while it had experienced many ups and downs over three centuries had always survived and – given stable internal affairs and favorable external circumstances – represented a power that was recognized and at times even courted by others.2

It all started from small beginnings around the middle of the seventh century, south of that part of the Thermaic Gulf which in those days extended far west inland.3 There, on both sides of the Haliacmon, lay a region called Makedonis and within it – on the northern slopes of the Pierian mountains – the original Macedonian capital Aegae. It was from here that the Macedonians conquered Pieria, the coastal plain east of the Pierian mountains and the Olympus, as well as Bottiaea, the region extending west and north of the Thermaic Gulf up to the Axius, with the future capital Pella. Next they crossed the Axius and occupied the plain between this river and present-day Thessaloniki. Thus they established control over the whole area around the Gulf and finally, just before the end of the sixth century, they also took over the regions of Eordaea and Almopia which bordered the central plain on the western and northwestern sides. The capture of Eordaea, beyond the mountain ridge sealing off the plain to the west, allowed the Macedonian kings to reach further into upper Macedonia, where the regions of Lyncus, Orestis, and Elimeia lay, enclosed by mountains and with their own rulers, whose adherence to the Macedonian kingdom was dependent on the strength of its central rule at any one time. It is impossible now to ascertain when the Macedonian kings first approached these mountain areas, while the further expansion toward the east falls into the period after the failure of Xerxes’ campaign.

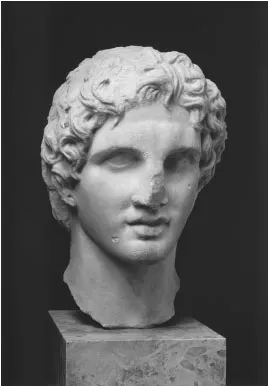

Figure 1.1 Bust of Alexander the Great, c.340–330 BC (copy?), as a youth. Acropolis Museum, Athens. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York.

The early days of Macedonian history are obscure. The first certain reports relate to the time of Persian rule on European soil: around 510 the Persian general Megabazus conquered the area along the northern coast of the Aegean and accepted the surrender of the Macedonian king Amyntas I. During the Ionian Revolt the Macedonians too shook off Persian sovereignty, which was restored as early as 492. Amyntas’ son Alexander I therefore participated in Xerxes’ campaign as a subject of the Great King.4 Immediately after the Persian defeat at Plataea, Alexander defected and took possession of the regions of Anthemus, Mygdonia, Crestonia, and Bisaltia which lay between the Axius and Strymon. However, in the final years of his reign he sustained losses on the western banks of the Strymon. His successor, Perdiccas II, who ruled until 413, was not only unable to reverse the losses in the east but also had to contend with the endeavors of the rulers of upper Macedonia to establish independence. Moreover, in his time Macedonia was impeded by the Athenian naval empire and drawn into the conflicts of the Peloponnesian War. But Perdiccas was able to maneuver a way through the warring factions fairly successfully and thus for the most part to maintain the independence of his kingdom.

His son Archelaus was destined for a happier rule, since Athenian pressure had eased after the Sicilian disaster. Relations with the Athenians were virtually reversed as they relied on Macedonian timber for shipbuilding. Archelaus’ real contributions lay in domestic politics, his cultural efforts and military reforms. Not only did he accelerate the extension of the road network, but he also initiated the development of a heavily armed infantry which, as shown by the events of the Peloponnesian War, was yet lacking in Macedonia. In the final years of his rule Archelaus was able even to intervene in Thessaly in favor of the imperiled noble family of the Aleuadae, to gain territory and secure his influence in Larisa.5 The right conditions for further extending Macedonian control were therefore in place when Archelaus was murdered in 399.

“Macedonian kings tended to die with their boots on”6 – and indeed the years from 399 to 359 were marked by turmoil and disputed successions during which the position that Macedonia had gained under Archelaus could not be retained. It was only in the latter half of these forty years that Macedonia was once more strengthened internally and enjoyed a degree of external authority, and we shall see when and why this became possible.

However, before that period, the Macedonians saw no fewer than four rulers within the six years, of whom we know little except that most of them came to a violent end and that the kingdom lost territories under them, at least in the east. We can picture Macedonia’s troubles more clearly in the first years of the rule of Amyntas III, who ascended the throne in 393.7 Soon after, Amyntas came under threat from the Illyrians and entered into a defensive alliance with the Chalcidian League which had become an important power on the north coast of the Aegean; he paid for this by ceding the Anthemus, the fertile valley southeast of present-day Thessaloniki. This alliance, however, did not save him from being temporarily expelled from his country. Only in the second half of the 380s was Amyntas secure enough to reclaim from the Chalcidians the land that he had ceded. Not only did they refuse to return it, but they for their part intervened in Macedonian affairs and forced Amyntas to turn to the Spartans who sent an army north in 382. The Olynthian War which began thus was, according to Xenophon’s report, fought mainly by the Spartans and their allies. The Macedonians did not contribute any military force worth mentioning, although Derdas, ruler of the Elimeia, and his cavalry provided useful support. Derdas and his territory are portrayed as being independent of the Macedonian king, and the other upper Macedonian kingdoms appear to have broken away at that time. In 379 the Chalcidian League was dissolved. Amyntas regained the Anthemus, but, according to Xenophon, the Spartans did little otherwise to strengthen the rule of the Macedonian king.8

Isocrates, a slightly older contemporary of Xenophon, however, took quite a different view. In his Panegyricus, published in 380, he castigates Spartan politics of the time with harsh words, introducing as one example among others that the Spartans had helped to extend the rule of the Macedonian king Amyntas, the Sicilian tyrant Dionysius, and the Great King (126). If Isocrates wished to remain credible in his condemnation of Spartan politics, he could not have included a completely insignificant Macedonian king in his trio of those then in power on the boundaries of the world of the Greek poleis. Therefore in 380 Amyntas must have been a political power not to be despised, even if in previous years he had suffered domestic and external problems. Isocrates also had something to say about this when he published his Archidamus in the 360s. Here Amyntas serves as a perfect example of what can be achieved by sheer determination: after he had been vanquished by his barbarian neighbors and robbed of all Macedonia, he regained his whole realm within three months and ruled without interruption into ripe old age (46). Isocrates could make such an assertion only if Amyntas was recognized as a ruler to be reckoned with even after his death.

In the context of a trial in 343, the Athenian Aeschines similarly identifies Amyntas as a political figure of some significance, when he records that Amyntas had been represented by a delegate at a Panhellenic congress (of which there were three between 375 and 371) but had full power over that delegate’s vote (2.32). According to this, Amyntas III was regarded as a full member of the community of Greek states at least toward the end of the 370s. The Athenians had already regarded him as such a little earlier in the 370s when they entered into an alliance with him (SIG3 157; Tod 129), the details of which unfortunately are not known, but which was probably connected to the expansion of Athenian naval power at the time. We know that in the year 375 the ship timber required came from Macedonia (Xen. Hell. 6.1.11). Macedonian ship timber was clearly once more in demand, and therefore the initiative to reach an agreement is likely to have come from the Athenians. In any case this agreement provides additional evidence that Macedonia had again joined the circle of states able to pursue their own policies.

Amyntas’ son Philip II is unwittingly responsible for the negative picture which both later sources and modern scholars have painted of him. In fact, Philip not only eclipsed the achievements of his predecessors, but also induced contemporary writers such as Theopompus, and later universal historians like Diodorus and modern historians, to portray him as almost the god-sent savior of a Macedonia sunk into chaos. Amyntas, with his stamina and energy, had already slowly overcome the disorder following Archelaus’ murder, although he also benefited from the shifts in power around Macedonia, and he left his sons a fairly well-secured kingdom when he died in 370/69.

The general state of affairs remained essentially favorable to the further rise of Macedonian power for his successors. But inner stability and continuity in the succession were needed as well as favorable external conditions. That it had taken Amyntas more than ten years to rebuild the kingdom, and that previously six years of disputes over the succession had been sufficient to bring Macedonia to the brink of disaster, show how quickly what had been achieved could be jeopardized. However, at this point a period of internal turmoil and struggle for the throne, as well of major external interference, soon commenced once more.

The succession of 370/69 went smoothly: Alexander II, the eldest son from Amyntas’ marriage to Eurydice, came to the throne, which in itself shows that Amyntas had again established order. The Illyrians, however, were of a different mind and invaded Macedonia. Pausanias, a relation of the ruling house who lived in exile, used the resulting absence of the young king to invade the country from the east. In this predicament the king’s mother Eurydice turned to the Athenian general Iphicrates who had been dispatched to win back Amphipolis and asked him for help. Iphicrates, gladly taking the opportunity to place the Macedonian king under an obligation, succeeded in expelling Pausanias.9

With this Alexander’s rule was secured, particularly since he had managed to ward off the Illyrian threat. The young king also began to assume the external status his father had achieved in his last year of rule, for the Thessalian Aleuadae called on his support against the tyrant Alexander of Pherae. The Macedonian king appeared with his army in Larisa, was allowed to enter the town, and took the castle after a short siege. Crannon likewise fell into his hands shortly afterward. But instead of handing over the towns to the Thessalian nobility, he kept them himself and installed garrisons in them. This turn of events was not what the Thessalian nobles had expected; they therefore turned to the Thebans who sent Pelopidas to their aid. Pelopidas marched north with an army and liberated Crannon and Larisa from Macedonian rule.

In the mean time Alexander II had been forced to return to Macedonia, for his brother-in-law Ptolemaeus had risen against him. Both parties turned to Pelopidas and called on him to be the arbiter. In order to insure that his arrangements would last and to retain a bargaining tool against the Macedonian king, Pelopidas received Alexander’s youngest brother Philip and thirty sons from the leading families as hostages. Thus the position of power gained under Amyntas III and inherited by Alexander II was quickly lost again and the country once more came under the influence of the then predominant power in Greece, but this was also due to their own mistakes. The state of affairs was to continue for some time. As soon as Pelopidas departed after settling the internal dispute, Alexander II was killed in the winter of 369/8.

As one of the closest male relatives, Ptolemaeus became guardian of Perdiccas, Alexander’s younger brother, and assumed the reins of government. The friends of the murdered ruler, however, regarded him as a usurper and in the summer of 368 turned to Pelopidas, who once more entered Macedonia. Ptolemaeus was forced to declare himself ready to come to an arrangement and to undertake to safeguard the rule for Alexander’s brothers, Perdiccas and Philip. Moreover, he had to agree to an alliance with Thebes and surrender his son and fifty nobles as hostages to guarantee his loyalty. Once more Macedonia was at the mercy of external forces, and again as a result of internal turmoil.

In 365 Perdiccas III succeeded in ridding himself of his guardian Ptolemaeus. Soon after assuming his rule, he decided to make common cause with the Athenians, to work with their commander Timotheus who was operating off the Macedonian coastline, and to take joint action with him against the Chalcidians and Amphipolis. Timotheus gained Potidaea and Torone on the Chalcidian peninsula, but was unable to achieve anything against Amphipolis. Soon afterward, the Athenians sent a cleruchy to Potidaea in order to secure his new acquisition, which occupied a strategic position.

Working with Timotheus is likely to have opened the Macedonian king’s eyes to the Athenians’ political ambitions for power and their by this time very limited capabilities, and to have strengthened his self-confidence, for he soon defected from them and secured Amphipolis through a garrison. Thus Perdiccas ended up on hostile terms with both the Athenians and the Chalcidians, who were themselves also at war with each other, and Athens’ power continued to wane. Overall Macedonia was again on the rise, after the rightful ruler had assumed the throne in Perdiccas and overcome initial problems. He was now able to begin to consolidate the kingdom and to secure it externally. As part of this, he also appears to have reasserted control over the upper Macedonian kingdoms. He also resolved to stop the Illyrians, who had plagued Macedonia since the times of Amyntas III, but was at last defeated in a great battle and fell with 4,000 of his men.

In this situation Perdiccas’ brother Philip proceeded with determination, military ability, and diplomatic skill, first to stabilize Macedonia, and then to pursue a course of expansion by making the most of each opportunity as it presented itself.10He was able to eliminate the pretenders to the throne who almost always quickly appeared in Macedonia in such circumstances; his next step was to secure the borders of the kingdom and their immediate approaches. In this he benefited from the situation in Greece: the Spartans, who acted as if they had been the masters of Greece for some time and had even intervened in the years 382–379 in favor of the then Macedonian king, had been eliminated as a leading power since their defeat at Leuctra (371) and limited to the Peloponnese in their political ambitions. From 357 to 355 the Athenians were entangled in conflicts with some of their allies, and the Second Athenian Confederacy was falling apart. The Thebans’ power likewise was crumbling: where ten years earlier they had still exerted crucial influence as far as Macedonia and even on the Peloponnese, now even their attempt at chastising the insubordinate Phocians failed. Instead, these occupied the sanctuary of Delphi in the early summer of 356 and proceeded to form a large army of mercenaries with the help of its treasures and to hold their own against the other members of the Amphictyony. Finally, the situation in Thrace was also advantageous for Philip after its king Cotys, who had succeeded in reuniting the kingdom, was murdered in the summer of 360 and Thrace was broken up into three parts in the subsequent battle for the succession. Thus the 350s saw convincing successes by Philip on all borders of his kingdom.

The borders to the west and north caused the fewest...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Chronology

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Journal and Serial Abbreviations

- Map

- Introduction

- 1: The Macedonian Background

- 2: Alexander’s Conquest of Asia

- 3: The Diadochi, or Successors to Alexander

- 4: A King and His Army

- 5: The Court of Alexander the Great as Social System

- 6: Alexander and the Greeks

- 7: Alexander and the Greeks

- 8: The Empire of Darius III in Perspective

- 9: Alexander and the Persian Empire, between “Decline” and “Renovation”

- 10: Alexander and his “Terrible Mother”

- 11: Alexander’s Sex Life

- 12: Heroes, Cults, and Divinity

- 13: Alexander’s Image in the Age of the Successors

- 14: Roman Alexanders:

- 15: The Construction of a New Ideal

- 16: Power, Passion, and Patrons

- Bibliography

- Index