eBook - ePub

Biophilic Design

The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biophilic Design

The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life

About this book

"When nature inspires our architecture-not just how it looks but how buildings and communities actually function-we will have made great strides as a society. Biophilic Design provides us with tremendous insight into the 'why,' then builds us a road map for what is sure to be the next great design journey of our times."

-Rick Fedrizzi, President, CEO and Founding Chairman, U.S. Green Building Council

"Having seen firsthand in my company the power of biomimicry to stimulate a wellspring of profitable innovation, I can say unequivocably that biophilic design is the real deal. Kellert, Heerwagen, and Mador have compiled the wisdom of world-renowned experts to produce this exquisite book; it is must reading for scientists, philosophers, engineers, architects and designers, and-most especially-businesspeople. Anyone looking for the key to a new type of prosperity that respects the earth should start here."

-Ray C. Anderson, founder and Chair, Interface, Inc.

The groundbreaking guide to the emerging practice of biophilic design

This book offers a paradigm shift in how we design and build our buildings and our communities, one that recognizes that the positive experience of natural systems and processes in our buildings and constructed landscapes is critical to human health, performance, and well-being. Biophilic design is about humanity's place in nature and the natural world's place in human society, where mutuality, respect, and enriching relationships can and should exist at all levels and should emerge as the norm rather than the exception.

Written for architects, landscape architects, planners,developers, environmental designers, as well as building owners, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life is a guide to the theory, science, and practice of biophilic design. Twenty-three original and timely essays by world-renowned scientists, designers, and practitioners, including Edward O. Wilson, Howard Frumkin, David Orr, Grant Hildebrand, Stephen Kieran, Tim Beatley, Jonathan Rose, Janine Benyus, Roger Ulrich, Bert Gregory, Robert Berkebile, William Browning, and Vivian Loftness, among others, address:

*

The basic concepts of biophilia, its expression in the built environment, and how biophilic design connects to human biology, evolution, and development.

*

The science and benefits of biophilic design on human health, childhood development, healthcare, and more.

*

The practice of biophilic design-how to implement biophilic design strategies to create buildings that connect people with nature and provide comfortable and productive places for people, in which they can live, work, and study.

Biophilic design at any scale-from buildings to cities-begins with a few simple questions: How does the built environment affect the natural environment? How will nature affect human experience and aspiration? Most of all, how can we achieve sustained and reciprocal benefits between the two?

This prescient, groundbreaking book provides the answers.

-Rick Fedrizzi, President, CEO and Founding Chairman, U.S. Green Building Council

"Having seen firsthand in my company the power of biomimicry to stimulate a wellspring of profitable innovation, I can say unequivocably that biophilic design is the real deal. Kellert, Heerwagen, and Mador have compiled the wisdom of world-renowned experts to produce this exquisite book; it is must reading for scientists, philosophers, engineers, architects and designers, and-most especially-businesspeople. Anyone looking for the key to a new type of prosperity that respects the earth should start here."

-Ray C. Anderson, founder and Chair, Interface, Inc.

The groundbreaking guide to the emerging practice of biophilic design

This book offers a paradigm shift in how we design and build our buildings and our communities, one that recognizes that the positive experience of natural systems and processes in our buildings and constructed landscapes is critical to human health, performance, and well-being. Biophilic design is about humanity's place in nature and the natural world's place in human society, where mutuality, respect, and enriching relationships can and should exist at all levels and should emerge as the norm rather than the exception.

Written for architects, landscape architects, planners,developers, environmental designers, as well as building owners, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life is a guide to the theory, science, and practice of biophilic design. Twenty-three original and timely essays by world-renowned scientists, designers, and practitioners, including Edward O. Wilson, Howard Frumkin, David Orr, Grant Hildebrand, Stephen Kieran, Tim Beatley, Jonathan Rose, Janine Benyus, Roger Ulrich, Bert Gregory, Robert Berkebile, William Browning, and Vivian Loftness, among others, address:

*

The basic concepts of biophilia, its expression in the built environment, and how biophilic design connects to human biology, evolution, and development.

*

The science and benefits of biophilic design on human health, childhood development, healthcare, and more.

*

The practice of biophilic design-how to implement biophilic design strategies to create buildings that connect people with nature and provide comfortable and productive places for people, in which they can live, work, and study.

Biophilic design at any scale-from buildings to cities-begins with a few simple questions: How does the built environment affect the natural environment? How will nature affect human experience and aspiration? Most of all, how can we achieve sustained and reciprocal benefits between the two?

This prescient, groundbreaking book provides the answers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biophilic Design by Stephen R. Kellert,Judith Heerwagen,Martin Mador in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Theory of Biophilic Design

Chapter 1

Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design

Biophilic design is the deliberate attempt to translate an understanding of the inherent human affinity to affiliate with natural systems and processes—known as biophilia (Wilson 1984, Kellert and Wilson 1993)—into the design of the built environment. This relatively straightforward objective is, however, extraordinarily difficult to achieve, given both the limitations of our understanding of the biology of the human inclination to attach value to nature, and the limitations of our ability to transfer this understanding into specific approaches for designing the built environment. This chapter provides some perspective on the notion of biophilia and its importance to human well-being, as well as some specific guidance regarding dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design that planners and developers can employ to achieve this objective in the modern, especially urban, built environment.

Biophilia and Human Well-Being

As noted, biophilia is the inherent human inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes, especially life and life-like features of the nonhuman environment. This tendency became biologically encoded because it proved instrumental in enhancing human physical, emotional, and intellectual fitness during the long course of human evolution. People's dependence on contact with nature reflects the reality of having evolved in a largely natural, not artificial or constructed, world. In other words, the evolutionary context for the development of the human mind and body was a mainly sensory world dominated by critical environmental features such as light, sound, odor, wind, weather, water, vegetation, animals, and landscapes.

The emergence during the past roughly 5,000 years of large-scale agriculture, fabrication, technology, industrial production, engineering, and the modern city constitutes a small fraction of human history, a period that has not substituted for the benefits of adaptively responding to a largely natural environment. Most of our emotional, problem-solving, critical-thinking, and constructive abilities continue to reflect skills and aptitudes learned in close association with natural systems and processes that remain critical in human health, maturation, and productivity. The assumption that human progress and civilization is measured by our separation from if not transcendence of nature is an erroneous and dangerous illusion. People's physical and mental well-being remains highly contingent on contact with the natural environment, which is a necessity rather than a luxury for achieving lives of fitness and satisfaction even in our modern urban society.

Biophilia is nonetheless a “weak” biological tendency that is reliant on adequate learning, experience, and sociocultural support for it to become functionally robust. As a weak biological tendency, biophilic values can be highly variable and subject to human choice and free will, but the adaptive value of these choices is ultimately bound by biology. Thus, if our biophilic tendencies are insufficiently stimulated and nurtured, they will remain latent, atrophied, and dysfunctional. Humans possess extraordinary capacities for creativity and construction in responding to weak biological tendencies, and this ability constitutes in a sense the “genius” of humanity. Yet, this innovative capacity is a two-edged sword, carrying with it the potential for distinctive individual and cultural expression, as well as the potential for self-defeating expression through either insufficient or exaggerated expression of inherent tendencies. Thus, our creative constructions of the human built environment can be either a positive facilitator or a harmful impediment to the biophilic need for ongoing contact with natural systems and processes.

Looking at biophilic needs as an adaptive product of human biology relevant today rather than as a vestige of a now-irrelevant past, we can argue that the satisfaction of our biophilic urges is related to human health, productivity, and well-being. What is the evidence to support this contention? The data is sparse and diverse, but a growing body of knowledge supports the role of contact with nature in human health and productivity This topic is extensively discussed elsewhere, such as in chapters in this book by Ulrich, Hartig, Frumkin, and others. Still, the following findings are worth noting (summarized in Kellert 2005):

- Contact with nature has been found to enhance healing and recovery from illness and major surgical procedures, including direct contact (e.g., natural lighting, vegetation), as well as representational and symbolic depictions of nature (e.g., pictures).

- People living in proximity to open spaces report fewer health and social problems, and this has been identified independent of rural and urban residence, level of education, and income. Even the presence of limited amounts of vegetation such as grass and a few trees has been correlated with enhanced coping and adaptive behavior.

- Office settings with natural lighting, natural ventilation, and other environmental features result in improved worker performance, lower stress, and greater motivation.

- Contact with nature has been linked to cognitive functioning on tasks requiring concentration and memory.

- Healthy childhood maturation and development has been correlated with contact with natural features and settings.

- The human brain responds functionally to sensory patterns and cues emanating from the natural environment.

- Communities with higher-quality environments reveal more positive valuations of nature, superior quality of life, greater neighborliness, and a stronger sense of place than communities of lower environmental quality. These findings also occur in poor urban as well as more affluent and suburban neighborhoods.

These studies provide scientific support for the ancient assumption that contact with nature is critical to human functioning, health, and well-being. As the psychiatrist Harold Searles concluded some years ago (1960, 117): “The nonhuman environment, far from being of little or no account to human [health and] personality development, constitutes one of the most basically important ingredients of human existence.”

Restorative Environmental and Biophilic Design

Unfortunately, the prevailing approach to design of the modern urban built environment has encouraged the massive transformation and degradation of natural systems and increasing human separation from the natural world. This design paradigm has resulted in unsustainable energy and resource consumption, major biodiversity loss, widespread chemical pollution and contamination, extensive atmospheric degradation and climate change, and human alienation from nature. This result is, however, not an inevitable by-product of modern urban life, but rather a fundamental design flaw. We designed ourselves into this predicament and theoretically can design ourselves out of it, but only by adopting a radically different paradigm for development of the modern built environment that seeks reconciliation if not harmonization with nature.

This new design paradigm is called here “restorative environmental design,” an approach that aims at both a low-environmental-impact strategy that minimizes and mitigates adverse impacts on the natural environment, and a positive environmental impact or biophilic design approach that fosters beneficial contact between people and nature in modern buildings and landscapes.

Recognition of how much the modern built environment has degraded and depleted the health and productivity of the natural environment prompted the development of the modern sustainable or green design movement, and years of hard work has started to yield significant change in design and construction practices. Unfortunately, the prevailing approach to sustainable design has almost exclusively focused on the low-environmental-impact objectives of avoiding and minimizing harm to natural systems (e.g., Mendler et al. 2006). While necessary and commendable, this focus is ultimately insufficient, largely ignoring the importance of achieving long-term sustainability of restoring and enhancing people's positive relationship to nature in the built environment, what is called here biophilic design. Low-environmental-impact design results in little net benefit to productivity, health, and well-being. Buildings and landscapes, therefore, will rarely be sustainable over time, lacking significant benefits derived from our ongoing experience of nature. Cutting-edge low-environmental-impact technology inevitably becomes obsolete, and when this occurs, will people be motivated to renew and restore these structures? Sustainability is as much about keeping buildings in existence as it is about constructing new low-impact efficient designs. Without positive benefits and associated attachment to buildings and places, people rarely exercise responsibility or stewardship to keep them in existence over the long run.

Biophilic design is, thus, viewed as the largely missing link in prevailing approaches to sustainable design. Low-environmental-impact and biophilic design must, therefore, work in complementary relation to achieve true and lasting sustainability. The major objectives of low-environmental-impact design have been effectively delineated, focusing on goals such as energy and resource efficiency, sustainable products and materials, safe waste generation and disposal, pollution abatement, biodiversity protection, and indoor environmental quality. Moreover, the detailed specification of design strategies to achieve these goals has been incorporated into certification systems such as the U.S. Green Building Council's LEED rating approach.

In contrast, a detailed understanding of biophilic design remains meager (Kellert 2005, Heerwagen 2001). For the remainder of this chapter, therefore, dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design will be described to partially address this need. The following description identifies two basic dimensions of biophilic design, followed by six biophilic design elements, which in turn are related to some 70 biophilic design attributes. This specification can assist designers and developers in pursuing the practical application of biophilic design in the built environment.

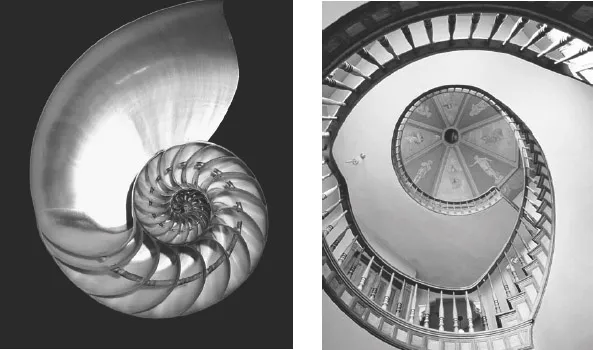

The first basic dimension of biophilic design is an organic or naturalistic dimension, defined as shapes and forms in the built environment that directly, indirectly, or symbolically reflect the inherent human affinity for nature. Direct experience refers to relatively unstructured contact with self-sustaining features of the natural environment such as daylight, plants, animals, natural habitats, and ecosystems. Indirect experience involves contact with nature that requires ongoing human input to survive such as a potted plant, water fountain, or aquarium. Symbolic or vicarious experience involves no actual contact with real nature, but rather the representation of the natural world through image, picture, video, metaphor, and more.

The second basic dimension of biophilic design is a place-based or vernacular dimension, defined as buildings and landscapes that connect to the culture and ecology of a locality or geographic area. This dimension includes what has been called a sense or, better, spirit of place, underscoring how buildings and landscapes of meaning to people become integral to their individual and collective identities, metaphorically transforming inanimate matter into something that feels lifelike and often sustains life. As René Dubos (1980, 110) argued:

People want to experience the sensory, emotional, and spiritual satisfactions that can be obtained only from an intimate interplay, indeed from an identification with the places in which [they] live. This interplay and identification generate the spirit of the place. The environment acquires the attributes of a place through the fusion of the natural and human order.

People are rarely sufficiently motivated to act as responsible stewards of the built environment unless they have a strong attachment to the culture and ecology of place. As Wendell Berry (1972, 68) remarked: “Without a complex knowledge of one's place, and without the faithfulness to one's place on which such knowledge depends, it is inevitable that the place will be used carelessly and eventually destroyed.” A tendency to affiliate with place reflects the human territorial proclivity developed over evolutionary time that has proven instrumental in securing resources, attaining safety and security, and avoiding ris...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: In Retrospect

- Part I: The Theory of Biophilic Design

- Part II: The Science and Benefits of Biophilic Design

- PART III: The Practice of Biophilic Design

- Contributors

- Image Credits

- Color Insert

- Index

- A WILEY BOOK ON Sustainable Design