![]()

Part I: Introduction

Chapter 1

What Is Project Portfolio Management?

INTRODUCTION

“I don’t understand, why aren’t these projects delivering as they promised?”

This familiar cry has been heard from business leaders and project managers for some time now. Thousands of books and articles offer answers to this question, but the frustration continues. An idea that is gaining ever more traction in answering this question is Project Portfolio Management—the concept of focusing on the selection and management of a set of projects to meet specific business objectives. But when business leaders and project managers review this concept of PPM, their response is often: “This portfolio management stuff sounds way too simple. It just can’t be the answer!”

However, this response itself begs a question. If PPM is so simple and self-evident, why does it have such limited traction in organizations that are apparently so in need of its help? The logic of simply reviewing all projects underway in an organization, making sure they meet business needs, align with strategy, and provide real value does seem self-evident. Practice and observation tells us that PPM does work, when properly implemented. Unfortunately, what our experience tells us is that a lot of the time, it’s the implementation of PPM that leaves much to be desired and results in responses such as:

- “This process is too complex.”

- “We don’t have time to go through all this business case stuff—we need to get to work!”

- “This process is really needed for our organization’s business projects, but mine are different and don’t need to go through all those steps.”

Apparently PPM isn’t so self-evident after all. So what do we do?

Business leaders want the business to be successful. They want sound business processes they can depend upon. Project managers want their projects to be successful, so the company will be successful. So it sounds like we’re all on the same page, right? Wrong. Here’s where the age-old dilemma rears its ugly head for the business leader and project manager alike—there are limited resources, lots of ideas and projects, only so much time in a day and … oh yes, things keep changing.

This is when it becomes important for us to be able to make tough decisions: which projects do we invest in (and over what timeframe) to be successful? This requires good facts to make the right decisions. We need to be able to examine the facts when changes and issues arise that require a decision be made and acted upon. And these facts need to be weighed against our gut feel for the situation (sometimes called “experience”)—by both business leaders and project managers—and then a decision made. This, too, may seem to be self-evident, but is it really? So, how do we get the facts and data we need? And how do we know we’re making the right decisions?

This is where the power of PPM comes into the picture. PPM forces us to think strategically: what we want our organizations to be, and what we should be doing to get there. But it’s not an easy fix. When implemented properly, PPM often requires organizational change across the business, and that can be very difficult to carry through. However, as this book demonstrates, the potential benefits for the business can be immense.

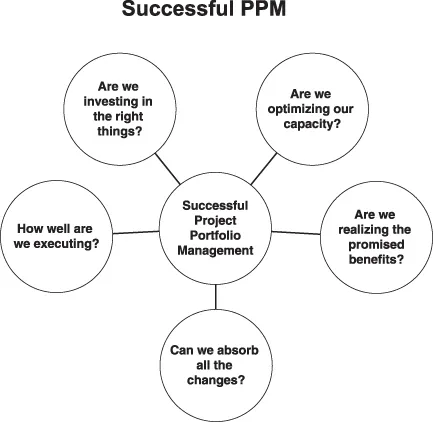

SUCCESSFUL PPM

PPM invariably changes the culture of the business because it demands we ask the hard questions. Five such questions rise to the top of the list and will be explored in depth in the chapters that follow (see Figure 1.1). Your ability to answer these questions accurately will determine how well you’ve implemented PPM in your organization:

1. Are we investing in the right things?

2. Are we optimizing our capacity?

3. How well are we executing?

4. Can we absorb all the changes?

5. Are we realizing the promised benefits?

THE FIVE QUESTIONS IN BRIEF

Let’s take a brief look at the five questions we will explore in depth later.

“Are we investing in the right things?”

Any task, activity, project, or program requires either money, equipment, material, people’s time, or some combination of these. And when you look at it, the equipment, material, and even people’s time can be readily converted to a common unit of measure: money. Therefore, since PPM is looking at these things as a whole, and they all take money in some form, then it only makes sense to view them as “investments.” If our projects are investments, then doesn’t it make sense to ask whether we’re actually spending our money and time on the right things? And, so, we have the first question: “Are we investing in the right things?”

A sound PPM capability requires, at a minimum, four things: informed managers, involved participants (including the right level of executive sponsorship), good facilitation, and appropriate processes, systems, and tools. (Okay, that may technically be six things—we just view processes, systems, and tools as a single, integrated item—but you get the picture).

Since money is very much a limited resource, we must figure out a way to invest in the right things. This is a balancing act between the desire to fulfill the business strategies, the limited money we have to invest, and knowing when is the right time to start a project. Along with deciding which new projects deserve investment, we need to monitor the progress of active projects so that, if they’re not reaping the expected benefits, they can be closed down, and their allocated capital can be recovered to apply to more beneficial projects.

However, this is not all. Businesses operate in a dynamic environment that shifts strategic objectives over time. Projects that are strategically aligned today may not be tomorrow. So PPM must also be a dynamic process. Ideally, the portfolio would be optimized in real-time (or near real-time). Also, since not all good projects can be approved immediately, what is “right” for the portfolio may not be optimal for all the potential projects competing for funding.

Foundational Tool

The Business Case

Along the way to successfully implementing PPM, we discovered that there is a foundational, and essential, tool that is often overlooked. This tool is the Business Case. It provides the necessary facts and data for understanding the value, cost, and benefit of implementing a project. It also lists the assumptions used to reach the touted conclusions, the various options considered, and the required cash flow for implementing the project.

Ultimately, the business case elicits a decision about the project, and you’re given one of three choices:

One of the keys to making the best decision is understanding the criteria used to judge and prioritize projects. The company already has projects under way, and usually has a list of possible projects to add to that inventory. So how do you decide which ones to add, and when to add them? The business case is your fundamental tool for providing facts and data about each decision criterion to enable apples-to-apples comparisons to be made among projects in determining which ones should become part of the portfolio.

Lesson Learned

Even “mandatory” projects have options.

Let us share one invaluable lesson we have learned the hard way: even “mandatory” projects have options (“mandatory” projects are ...