eBook - ePub

Dyslexia, Speech and Language

A Practitioner's Handbook

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dyslexia, Speech and Language

A Practitioner's Handbook

About this book

This authoritative handbook presents current ideas on the relationship between spoken and written language difficulties. It provides clinical and educational perspectives on the assessment and management of children's reading and spelling problems. The book begins with a theoretical overview.

The second edition continues the theme of linking theory and practice. It is aimed at practitioners in the fields of education, speech and language therapy, and psychology. All original chapters have been updated and new chapters are added to reflect current developments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dyslexia, Speech and Language by Margaret J. Snowling, Joy Stackhouse, Margaret J. Snowling,Joy Stackhouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Learning Disabilities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Language skills and learning to read: the dyslexia spectrum

Children vary in the age at which they first start to talk. For many families, late talking might go unnoticed, particularly if the child in question is the first born of the family and no comparisons can be made. Later in the preschool years, children may be difficult to understand; they might have a large repertoire of their ‘own words’ that others find unintelligible. Such utterances are often endearing, the source of family amusement, and no one worries much because an older sibling can translate. But speech or language delay can be the first sign of reading difficulties, difficulties that will come to the fore only when the child starts school; a key issue therefore is when is ‘late talking’ a concern, and when is it just part of typical variation?

Language is a complex system that requires the coordinated action of four interacting subsystems. Phonology is the system that maps speech sounds on to meanings, and meanings are part of the semantic system. Grammar is concerned with syntax and morphology (the way in which words and word parts are combined to convey different meanings), and pragmatics is concerned with language use. An assumption of our educational system is that by the time children start school, the majority are competent users of their native language. This is a reasonable assumption, but those who are not ‘very good with words’ start out at a disadvantage, not only in speaking and listening skills, but also, as this book will demonstrate, in learning to read.

Thus, oral language abilities are the foundation for later developing literacy skills. It is, however, important to distinguish speech skills from language abilities when considering literacy development. Learning to read in an alphabetic system, such as English, requires the development of mappings between speech sounds and letters – the so-called alphabetic principle – and this depends on speech skills. Wider language skills are required to understand the meanings of words and sentences, to integrate these into texts and to make inferences that go beyond the printed words. Before examining evidence concerning how language difficulties compromise literacy in dyslexia and related disorders, we begin with a short historical review of the concept of dyslexia.

The concept of dyslexia

Arguably, the scientific study of dyslexia first came to prominence in the late 1960s when one of the main issues of debate was whether ‘dyslexia’ was different from plain poor reading. Studies of whole-child populations, notably the epidemiological studies of Rutter and his colleagues, provided data about what differentiated children with specific reading problems (dyslexia) from those who were slow in reading but for whom reading was in line with general cognitive ability (Rutter and Yule, 1975). The results of these studies were not good for proponents of the ‘special’ condition of dyslexia. In fact, there were relatively few differences in aetiology between children with specific reading difficulty and the group they described as generally ‘backward readers’. The group differences that were found included a higher preponderance of males among children with specific reading difficulties and more specific delays and difficulties with speech and language development. On the other side of the coin, the generally backward group showed more hard signs of brain damage, for example cerebral palsy and epilepsy. Important at the time, the two groups differed in the progress they had made at a 2 year follow-up. Contrary to what might have been expected on the basis of their IQ, the children with specific reading difficulties (who had a higher IQ) made less progress in reading than the generally backward readers. This finding suggested that their problems were intransigent, perhaps because of some rather specific cognitive deficit. Note, however, that this differential progress rate has not been replicated in more recent studies (Shaywitz et al., 1992), perhaps because advances in knowledge have led to better interventions (see Snowling, 2000, for a review).

Following on from these large-scale studies, the use of the term ‘dyslexia’ became something of a taboo in educational circles. Instead, children were described as having specific reading difficulties or specific learning disability if there was a discrepancy between their expected attainment in reading, as predicted by age and IQ, and their actual reading attainment. The use of IQ as part of the definition of ‘dyslexia’ has, however, fallen from favour. First, IQ is not strongly related to reading. Indeed, many children with a low IQ can read perfectly well even though they may encounter reading comprehension difficulties. Second, and perhaps more importantly, measures of verbal IQ may underestimate cognitive ability among poor readers who have mild language impairments. As a result, adherence to the ‘discrepancy definition’ of dyslexia can disadvantage those children with the most severe problems whose apparently low verbal IQ may obscure the ‘specificity’ of the reading problem.

Another problem with the discrepancy definition of dyslexia is that it cannot be used to identify younger children who are too young yet to show a discrepancy. In fact, many children who fail to fulfil diagnostic criteria at one age may do so later in the school years (Snowling, Bishop and Stothard, 2000). Moreover, the definition is silent with regard to the ‘risk’ signs for dyslexia, and how to diagnose dyslexia in young people who may have overcome basic literacy difficulties. What is needed to get around these difficulties is a set of positive diagnostic criteria for dyslexia. It is just such criteria that have been sought by psychologists working in the field of reading disabilities.

Cognitive deficits in dyslexia

At about the same time as the first epidemiological studies were being conducted, cognitive psychologists began comparing groups of normal readers and readers with dyslexia using a range of experimental paradigms. In a landmark review, Vellutino (1979) synthesized the extant evidence to propose the verbal deficit hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, children with dyslexia are subject to problems centring on the verbal coding of information that create specific problems for learning to read in an alphabetic script. Arguably, since that time, the most widely accepted view of dyslexia has been that it can be considered to be part of the continuum of language disorders. There has, however, been a gradual shift from the verbal deficit hypothesis to a more specific theory: that dyslexia is characterized by phonological processing difficulties (see Vellutino et al., 2004, for an updated review).

Children with dyslexia typically have difficulties that primarily affect the phonological domain; the most consistently reported phonological difficulties are limitations of verbal short-term memory and, more directly related to their reading problems, problems with phonological awareness. There is also evidence that children with dyslexia have trouble with long-term verbal learning. This problem may account for many classroom difficulties, including problems memorizing the days of the week or the months of the year, mastering multiplication tables and learning a foreign language. In a similar vein, this problem may be responsible for the word-finding difficulties and poor vocabulary development often observed in children with dyslexia.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that a number of authors have argued that difficulties with phonological awareness are not a universal phenomenon in dyslexia. Instead, children learning to read in more regular or transparent orthographies than English, in which the relationships between spellings and their sounds are consistent (e.g. German, Italian, Spanish or Greek), learn to decode quickly, while at the same time rapidly acquiring an awareness of the phonemic structure of spoken words (Ziegler and Goswami, 2005). It follows that, in these languages, deficits in phonological awareness are less good markers of dyslexia. Instead, impairments of phonological processing, such as rapid naming or poor verbal memory, are more sensitive diagnostic signs in these writing systems. Notwithstanding this proviso, the strength of the evidence pointing to the phonological deficits associated with dyslexia has led Stanovich and his colleagues to propose that dyslexia should be defined as a core phonological deficit. Importantly, within the phonological core-variable difference model of dyslexia (Stanovich and Siegel, 1994), poor phonology is related to poor reading performance irrespective of IQ and also, it seems, irrespective of language background (Caravolas, 2005; Goulandris, 2003).

Phonological representations, learning to read and dyslexia

Although the role of visual deficits in dyslexia continues to be debated (Stein and Talcott, 1999), the best candidate for the cause of dyslexia is an underlying phonological deficit. A useful way in which to think about this is that children with dyslexia come to the task of learning to read with poorly specified phonological representations – the way in which their brain codes phonology is less efficient than that of normally developing readers. As we have seen, this problem at the level of phonological representation causes a range of typical symptoms, such as those described above. It is, however, important to understand why a deficit in spoken language should affect the acquisition of written language.

Studies of normal reading development offer a framework for considering the role of phonological representations in learning to read and for understanding the problems of dyslexia. At the basic level, learning to read requires the child to establish a set of mappings between the letters (graphemes) of printed words and the speech sounds (phonemes) of spoken words. These mappings between orthography and phonology allow novel words to be decoded and provide a foundation for the acquisition of later and more automatic reading skills. In English, they also provide a scaffold for learning multi-letter (e.g. ‘ough’, ‘igh’), morphemic (‘-tion’, ‘-cian’) and inconsistent (‘-ea’) spelling–sound correspondences. Indeed, the early developing ability of the child to ‘invent’ spellings that are primitive phonetic transcriptions of spoken words (e.g. <LEVNT> for ELEPHANT) is one of the best predictors of later reading and spelling success (Caravolas, Hulme and Snowling, 2001). More broadly, there are strong relationships between phonological skills and reading ability throughout development and into adulthood, when the phonological deficits of people with dyslexia persist (Bruck, 1992).

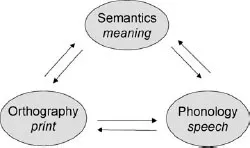

More formally, the relationship between oral and written language skills has been simulated in computational models of the reading process. In the triangle model of Plaut and colleagues (shown in Figure 1.1), reading is conceptualized as the interaction of a phonological pathway mapping between letters and sounds and a semantic pathway mapping between letters and sounds via meanings (Plaut et al., 1996). In the early stages of learning to read, children’s attention is devoted to establishing the phonological pathway (‘phonics’). Later, children begin to rely increasingly on word meanings to gain fluency in their reading. We can think of this as an increase in the role of the semantic pathway, something which is particularly important for reading exception words in English, such as YACHT and PINT, words that cannot be processed efficiently by the phonological pathway. Arguably, however, this model is limited for considering the risk of reading difficulties among children with spoken language impairments; the model is of single-word reading, but most reading takes place in context. Language skills that encompass grammar and pragmatics are needed for making use of context. Children with dyslexia do not typically have problems with these processes, but children with wider language difficulties almost certainly do.

Within this model of reading development, deficits at the level of phonological representation constrain the reading development of children with dyslexia (Snowling, 2000). A consequence is that although such children may learn to read words by rote (possibly relying heavily on context), they have difficulty generalizing this knowledge. For English readers with dyslexia, a notable consequence is poor non-word reading (Rack, Snowling and Olson, 1992). In contrast, the semantic skills of readers with dyslexia are, by definition, within the normal range, and these can be used to facilitate the development of word reading (Nation and Snowling, 1998a).

Figure 1.1 Triangle model of reading (after Seidenberg and McClelland, 1989). In this model, the mappings between orthography to phonology comprise the phonological pathway; mappings between orthography and phonology via semantics comprise the semantic pathway.

In short, learning to read is an interactive process to which the child brings all of his or her linguistic resources. It is, however, phonological processing that is most strongly related to the development of reading and the source of most dyslexic problems in reading and spelling. The phonological representations hypothesis therefore provides a parsimonious explanation of the disparate symptoms of dyslexia that persist through school to adulthood. It also makes contact with theories of normal reading development and with scientific studies of intervention. Here, the consensus view is that interventions that promote phonological awareness in the context of a highly structured approach to the teaching of reading have a positive effect in both preventing reading failure and ameliorating dyslexic reading difficulties (see Chapter 9 in this volume; Troia, 1999). There is also biological evidence in support of the theory.

Biological evidence in support of the phonological deficit hypothesis

It has been known for many years that poor reading tends to run in families, and there is now conclusive evidence that dyslexia is heritable. Gene markers have been identified on chromosomes 6, 15 and 18, but we are still a long way from understanding the precise genetic mechanisms involved. What we do know is there is as much as a 50 per cent probability of a boy becoming dyslexic if his father is dyslexic (about 40 per cent if his mother is affected) and a somewhat lower probability of a girl developing dyslexia. What is inherited is not of course reading disability per se but the risk of reading problems, mediated via speech and language delays and difficulties. The results of large-scale twin studies suggest that there is heritability of the phonological (‘phonic’) aspects of reading and that phonological awareness shares heritable variance with this (Olson, Forsberg and Wise, 1994).

Studies of readers with dyslexia using brain imaging techniques also supply a piece in the jigsaw (see Chapter 3 in this volume). In one such study, we investigated differences in brain function between dyslexic and normal readers while they performed two phonological processing tasks (Paulesu et al., 1996). This study involved five young adults with a well-documented history of dyslexia; all of these people had overcome their reading difficulties, but they had residual problems with phonological awareness. Under positron emission tomography scanning, they completed two sets of parallel tasks. The phonological tasks were a rhyme judgement and a verbal short-term memory task; the visual tasks were visual similarity judgement and visual short-term memory. Although these adults with dyslexia performed as well as controls on the experimental tasks, they showed different patterns of left hemisphere brain activation from controls during performance on the phonological processing tasks. The brain regions associated with reduced activity were those involved in the transmission of language and, plausibly, allowed the translation between the perception and the production of speech. It is therefore possible to speculate that this area may be the ‘seat’ of the problems viewed at the cognitive level, as a difficulty in setting up phonological representations.

Individual differences in dyslexia

A significant issue for the phonological representation view is that of individual differences. The phonological deficit theory has no difficulty explaining the problems of a child with poor word attack skills, who cannot read non-words and whose spelling is dysphonetic (Snowling, Stackhouse and Rack, 1986). There are also, however, children with dyslexia who appear to have mastered alphabetic skills. Such children have been referred to as dev...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Contributors

- CHAPTER 1: Language skills and learning to read: the dyslexia spectrum

- CHAPTER 2: Speech and spelling difficulties: what to look for

- CHAPTER 3: The dyslexic brain

- CHAPTER 4: The prediction and screening of children’s reading difficulties

- CHAPTER 5: Assessing speech and language skills in the school-age child

- CHAPTER 6: Assessing reading and spelling skills

- CHAPTER 7: Assessing children’s reading comprehension

- CHAPTER 8: Short-term memory: assessment and intervention

- CHAPTER 9: Phonological awareness and reading intervention

- CHAPTER 10: Spelling: challenges and strategies for the dyslexic learner and the teacher

- CHAPTER 11: Developing handwriting skills

- CHAPTER 12: Managing the needs of pupils with dyslexia in mainstream classrooms

- CHAPTER 13: The assessment and management of psychosocial aspects of reading and language impairments

- CHAPTER 14: Supporting language and literacy in the early years: interdisciplinary training

- CHAPTER 15: Current themes and future directions

- References

- Author index

- Subject index