![]()

CHAPTER 1

Size Is Not a Strategy

In the past 20 years, no marketing concept has captured the collective business imagination more than “branding.” Every year, several important new books are written on the subject. And professional service firms from business consultancies to advertising agencies are advising clients on how to “brand” their offering.

Given the billions invested in this effort, it’s worth stepping back to examine the nature and value of brands. In answer to the question, “Why is a strong brand important?” one might say that it creates customer preference, lifts sales, or even makes the sales force’s job easier. But the most important answer to this question is that a brand commands a higher price. And the stronger the brand, the higher the price.

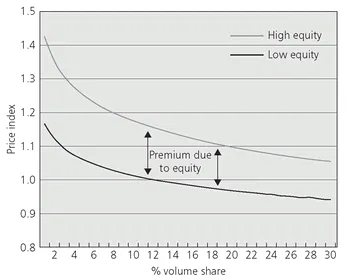

This phenomenon is indisputable; it’s been demonstrated numerous times by research and brand consultancies the world over. In one such recent study, international research firm Millward Brown looked at a variety of brands of differing sizes and indexed their price against the category. What they found, not surprisingly, is that “it is abundantly clear that brands with higher equity have a price premium over lower equity brands”1 (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The High-Equity Price Differential

Source: Adapted from “Brand Equity and the Bottom Line,” by Peter Walshe and Helen Fearn, Admap, March 2008.

Now consider the seemingly naïve question, “What’s the value of a higher price?” The answer is higher profits for the company that markets the brand.

Profit is the reason companies are in business—not sales, not revenues, not growth, but profit. And one thing trumps all others in the business mix when it comes to profitability: the pricing integrity of the brand.

MAINTAINING PRICING INTEGRITY

The investment companies make in “branding” is not just to sell more, but ultimately to decrease customers’ sensitivity to price. In fact, it could be argued that the default purpose of marketing is not to increase sales but rather to increase profits. More than anything else, profit is a direct result of protecting pricing integrity through powerful brand differentiation.

Even marketing programs that don’t do much to boost revenues can increase margins by differentiating brands and thus allowing companies to raise prices. In other words, while brand-building efforts may not always increase revenues in the short term, they produce the important result of allowing the brand to charge higher prices over the long term.

The value of premium pricing is significant. A study by McKinsey shows that reducing costs improves a company’s profits only marginally, whereas increasing the brand’s price improves profits dramatically. A 5 percent improvement in price can result in as much as a 50 percent improvement in profits.2

Says the author of Priceless, an exploration of the power of pricing, “Because profit margins are small to begin with, adding a percent or two can boost profits immensely. Very few interventions can have such an effect on the bottom line.”3

Nothing can improve a company’s bottom line better than protecting and enhancing its ability to command a higher price. This means that revenues are not the key metric of your firm’s success; profits are. Profit is driven mostly by price. Price is driven mostly by brand perception. This makes brand building an activity central to the success of every professional firm.

BETTER TO BE A PROFIT LEADER THAN A MARKET LEADER

Sadly, growth for the sake of growth has become enshrined as the goal of business. Wall Street wants its growth projections, and any company that is not consistently increasing market share is seen as an investment risk.

There are, of course, different kinds of growth: growth in sales, growth in market share, growth in market penetration, and so on. However, the only growth that really matters is growth in profitability. It’s easy to grow sales and market share and still be unprofitable. Companies—not just some, but most companies, including professional firms—routinely “buy” sales and market share by discounting. That kind of growth isn’t growth at all; it’s merely a form of unhealthy enlargement.

“Fixating on market share instead of profits actually tends to decrease profitability,” says Wharton’s J. Scott Armstrong. Former Wall Street Journal editor Richard Miniter argues that market share is “the fool’s gold of business.”4 A lot of commonly accepted assumptions about bigness are simply not true. A few of them are shown in Table 1.1.

What moral can be learned from this comparison of the assumptions versus the reality? Companies should be concerned with profit leadership, not market share leadership.

Table 1.1 The Myths of Bigness

| The Assumption | The Reality |

|---|

| Size creates pricing power. | The largest companies in the category are usually the first both to lower and match prices of competitors. They are also the most likely to use discounting and couponing as a tactic to buy more (unprofitable) market share. The bigger the company, the bigger the losses resulting from price wars. As most executives have learned, in a price war nobody wins. The only way a large company can create pricing power is the same way small companies do it: by creating and nurturing a highly differentiated brand. |

| The largest companies benefit from higher economies of scale. | Because of overdiversification, most large companies actually experience “diseconomies” of scale. It typically costs much more to serve the needs of a broad, mass market than it does a narrow, focused market. Larger companies also tend to have larger hierarchies that create significantly more overhead. The fallacy of the “efficiency” argument also applies to professional services. How many professional firms achieve twice the efficiencies with twice as many associates? |

| The largest companies attract and keep the best management talent. | The largest public companies almost always have the lowest return on assets, not the highest. They are also the most likely to be saddled with debt from unsuccessful mergers and acquisitions, usually resulting from an unhealthy obsession with being the biggest company in the category. |

| Size leads to profitability. | Actually, three times out of four the most profitable firm is not the one with the largest slice of the market. |

WHY BIGNESS DOESN’T LEAD TO GREATNESS

Jim Collins describes the stages through which successful companies pass on the way to their downfall. Second on the list: the undisciplined pursuit of more.5 Growth through acquisition—pursuing more for the sake of more—is usually an unsuccessful strategy. The majority of mergers and acquisitions fail, and sometimes spectacularly so (think DaimlerChrysler and AOL/TimeWarner). While some of these attempted partnerships build the CEO’s ego, they usually erode shareholder value.

Most business books feature examples of publicly owned companies, which largely have shaped the collective consciousness of the business community. We have come to accept business axioms (such as “grow or die”) that apply mostly to companies that are in a constant quest to satisfy shareholders. But privately held companies—which actually make up the majority of businesses—can and usually do operate under a different set of principles.6

The most exceptional private companies have chosen not to focus on revenue growth but rather to be the best at what they do. Many in fact place significant limits on their growth, choosing instead to focus on doing great work, providing great service, and creating a great place to work.

In professional services, the largest firm is seldom if ever the best. In the advertising world, one of the firm’s with the best reputation, the best pricing power, and the best work is far from being the largest. Crispin Porter + Bogusky employs fewer than 1,000 people (compared with the multinational agencies that employ tens of thousands), yet repeatedly has been named “Agency of the Year” by leading trade publications and business organizations. As is so often the case, the best firm in the category isn’t marginally better, but significantly outperforms other firms in the industry. In a recent annual compilation of worldwide creative awards, CP+B earned almost twice as many awards as the second-place firm. The gulf between the best and the rest is reflected in the observation of admen Jonathan Bond and Richard Kirshenbaum, who believe that “there are perhaps as few as 40 or 50 agencies in the United States that can actually manufacture a good campaign, and possibly 10 that do it consistently.”7

HIRED TO BE EFFECTIVE, NOT EFFICIENT

Advertising Age observes, “The list of great brands that have been damaged, even ruined, as they’ve been milked for growth rather than managed for profit is a long one—and it grows every year.”8

The unbridled quest for growth has played out in very visible ways in the marketing communications industry. Today, just five holding companies control 85 percent of the advertising expenditures in the world. In addition to creating leverage when negotiating media contracts, this roll up of marketing communications companies also was expected to produce significant economies of scale. It didn’t. What was the total “savings” resulting from consolidating the operations of thousands of agencies? It was less than .025 percent.9

The goal of professional knowledge firms should not be efficiency, but rather effectiveness. Can you imagine choosing a doctor based on efficiency instead of effectiveness? Tax advisors, lawyers, and marketing consultants are (or should be) hired for the same reasons. What’s ultimately important isn’t how hard you try or how many hours you spend, but rather whether you win the case, successfully keep a client out of tax trouble, or create more equity for your client’s brand.

Bad Clients Drive Out Good Clients

If the goal is greatness, not bigness, it follows that what professional firms need is not more business, but better business. My colleague Ron Baker has coined a truth he calls “Baker’s law”: Bad clients drive out good clients.

What is a “bad client?” A bad client is a low-value client, one that doesn’t add any value to the firm’s bottom line, professional satisfaction, or reputation.

• Low-value clients are unprofitable. There is simply no rational argument for keeping an unprofitable client. Look at your firm’s financials and you’ll likely see Pareto’s law in effect: 20 percent of your clients generate 80 percent of your income and profit. Generally speaking, about one-third of a firm’s clients actually cost the firm money.

• Low-value clients usually run your team ragged because they’re poorly organized, have unreasonable approval processes, and constantly change direction because they’re not focus...