![]()

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION TO BLENDED LEARNING

As blended learning emerges as perhaps the most prominent delivery mechanism in higher education, business, government, and military settings, it is vital to define it, as well as explain where it is useful and why it is important. This part, with chapters by Charles R. Graham, Elliott Masie, Jennifer Hofmann, and Ellen D. Wagner, does just that. These authors discuss the elements that are important to consider in blended learning while also touching on some of the emerging trends and issues.

In Chapter One, Charles R. Graham describes the historical emergence of blended learning as the convergence between traditional face-to-face learning environments and computer-mediated (or distributed) learning environments. He discusses four critical dimensions to interactions that occur in both of these environments (space, time, fidelity, and humanness) and presents a working definition for blended learning systems. This chapter also addresses current trends seen in both corporate and higher education, including blends that focus on enabling access and flexibility, enhancing current teaching and learning practices, and transforming the way individuals learn. The chapter ends with six important issues relevant to the design of blended learning systems, followed by some directions for the future.

In Chapter Two, Elliott Masie presents a brief and provocative perspective on blended learning. The central theme of his chapter is that all great learning is blended. In the predigital age, combinations of different learning contexts were used. Similarly, learning environments increasingly will incorporate “e elements” into varied instructional contexts. Masie outlines compelling reasons for why blending has been popular and will continue to be so.

In Chapter Three, Jennifer Hofmann addresses several of the typical challenges facing those who are attempting to implement blended solutions. She notes some of the common mistakes designers make: assuming that it will take less time to redesign an existing program than it would to design a blended program from scratch, putting too much emphasis on the “live” components of a training situation, and assuming that traditional facilitators are the best choices for managing a blended version of the training. An emphasis is placed on the importance of training the design team as well as the trainers. In addition, she outlines an example of a blended train-the-trainer course.

In Chapter Four, Ellen D. Wagner shares a vision for the next generation of blended learning. She addresses the impact that personal and mobile devices are likely to have on emerging models of blended learning and suggests that interaction strategies offer a useful means for enhancing individualization, personalization, and relevancy. She discusses current models of interaction and shares eleven ways that interaction can be used to focus on performance outcomes.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

BLENDED LEARNING SYSTEMS

Definition, Current Trends, and Future Directions

Charles R. Graham

The term blended learning is being used with increased frequency in both academic and corporate circles. In 2003, the American Society for Training and Development identified blended learning as one of the top ten trends to emerge in the knowledge delivery industry (Rooney, 2003). In 2002, the Chronicle of Higher Education quoted the president of Pennsylvania State University as saying that the convergence between online and residential instruction was “the single-greatest unrecognized trend in higher education today” (Young, 2002, p. A33). Also quoted in that article was the editor of the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, who predicted a dramatic increase in the number of hybrid (that is, blended) courses in higher education, possibly to include as many as 80 to 90 percent of all courses (Young, 2002).

So what is this blended learning that everyone is talking about? This chapter provides a basic introduction to blended learning systems and shares some trends and issues that are highly relevant to those who are implementing such systems. To accomplish these goals, the chapter addresses five important questions related to blended learning systems:

- What is blended learning?

- Why blend?

- What current blended learning models exist?

- What issues and challenges are faced when blending?

- What are the future directions of blended learning systems?

Background and Definitions

The first question asked by most people when hearing about blended learning is, “What is blended learning?” Although blended learning has become somewhat of a buzzword in corporate and higher education settings, there is still quite a bit of ambiguity about what it means (see Jones, Chapter Thirteen, this volume). How is blended learning different from other terms in our vernacular, such as distributed learning, e-learning, open and flexible learning, and hybrid courses? Some define the term so broadly that one would be hard pressed to find any learning system that was not blended (Masie, Chapter Two, this volume; Ross and Gage, Chapter Eleven, this volume). Others challenge the very assumptions behind blending as holding on to relics of an old paradigm of learning (Offerman and Tassava, Chapter Seventeen, this volume). In the first section of this chapter, I articulate a practical working definition for the term blended learning and provide a historical context for its emergence.

What Is Being Blended?

One frequent question asked when one hears about blended learning (BL) is, “What is being blended?” Although there is a wide variety of responses to this question (Driscoll, 2002), most of the definitions are just variations of a few common themes. The three most commonly mentioned definitions, documented by Graham, Allen, and Ure (2003), are:

- Combining instructional modalities (or delivery media) (Bersin & Associates, 2003; Orey, 2002a, 2002b; Singh & Reed, 2001; Thomson, 2002)

- Combining instructional methods (Driscoll, 2002; House, 2002; Rossett, 2002)

- Combining online and face-to-face instruction (Reay, 2001; Rooney, 2003; Sands, 2002; Ward & LaBranche, 2003; Young, 2002)

The first two positions reflect the debate on the influences of media versus method on learning (Clark, 1983, 1994a, 1994b; Kozma, 1991, 1994). Both of these positions suffer from the problem that they define BL so broadly that they encompass virtually all learning systems. One would be hard-pressed to find any learning system that did not involve multiple instructional methods and multiple delivery media. So defining BL in either of these two ways waters down the definition and does not get at the essence of what blended learning is and why it is exciting to so many people. The third position more accurately reflects the historical emergence of blended learning systems and is the foundation of the author’s working definition (see Figure 1.1).

The working definition in Figure 1.1 reflects the idea that BL is the combination of instruction from two historically separate models of teaching and learning: traditional face-to-face learning systems and distributed learning systems. It also emphasizes the central role of computer-based technologies in blended learning.

Past, Present, and Future

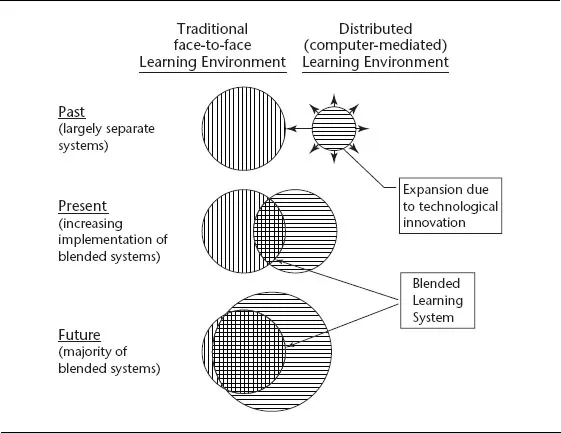

BL is part of the ongoing convergence of two archetypal learning environments. On the one hand, we have the traditional face-to-face learning environment that has been around for centuries. On the other hand, we have distributed learning environments that have begun to grow and expand in exponential ways as new technologies have expanded the possibilities for distributed communication and interaction.

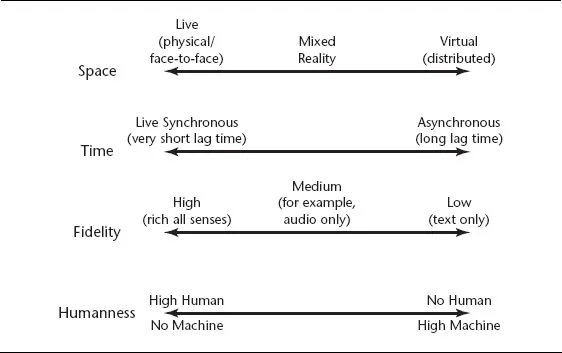

In the past, these two learning environments have remained largely separate because they have used different media and method combinations and have addressed the needs of different audiences (see Figure 1.2). For example, traditional face-to-face learning typically occurred in a teacher-directed environment with person-to-person interaction in a live synchronous, high-fidelity environment. On the other hand, distance learning systems emphasized self-paced learning and learning materials interactions that typically occurred in an asynchronous, low-fidelity (text only) environment.

Figure 1.3 shows the continuum for four critical dimensions of interactions that occur in both of these environments. Historically, face-to-face learning has operated at the left-hand side of each of these dimensions, and distributed learning has operated at the right of each of these dimensions. To a large degree, the media available placed constraints on the nature of the instructional methods that could be used in each environment. For example, it was not possible to have synchronous or high-fidelity interactions in the distributed environment. Because of these constraints, distributed learning environments placed emphasis on learner-material interactions, while face-to-face learning environments tended to place priority on the human-human interaction.

The rapid emergence of technological innovations over the past half-century (particularly digital technologies) has had a huge impact on the possibilities for learning in the distributed environment. In fact, if you look at the four dimensions, distributed learning environments are increasingly encroaching on instructional territory that was once possible only in face-to-face environments. For example, in the time and fidelity dimensions, communication technologies now allow us to have synchronous distributed interactions that occur in real time with close to the same levels of fidelity as in the face-to-face environment. In the humanness dimension, there is an increasing focus on facilitating human interaction in the form of computer-supported collaboration, virtual communities, instant messaging, and blogging. In addition, there is ongoing research investigating how to make machines and computer interfaces more social and human (the work with automated agents and virtual worlds, for example). Even in the space dimension, there are some interesting things happening with mixed reality environments (see Kirkley and Kirkley, Chapter Thirty-Eight, this volume) and environments that simultaneously facilitate both distributed and face-to-face interactions (see Wisher, Chapter Thirty-Seven, this volume).

The widespread adoption and availability of digital learning technologies has led to increased levels of integration of computer-mediated instructional elements into the traditional face-to-face learning experience. From the distributed learning perspective, we see evidence of the convergence in face-to-face residency requirements (Offerman and Tassava, Chapter Seventeen, this volume; Pease, Chapter Eighteen, this volume) and limited face-to-face events, such as orientations and final presentations (Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume). In addition, there is greater emphasis on person-to-person interaction, and increasing use of synchronous and high-fidelity technologies to mediate those interactions. Figure 1.2 depicts the rapid growth of distributed learning environments and its convergence with face-to-face learning environments. The intersection of the two archetypes depicts where blended learning systems are emerging.

Although it is impossible to see entirely what the future holds, we can be pretty certain that the trend toward blended learning systems will increase. It may even become so ubiquitous that we will eventually drop the word blended and just call it learning, as both Masie (see Chapter Two, this volume) and Massy (see Chapter Thirty, this volume) predict. But regardless of what we decide to call blended learning in the future, it is clear that it is here to stay. Therefore, it is imperative that we understand how to create effective blended learning experiences that incorporate both face-to-face and computer-mediated (...