- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Kellogg on Advertising and Media, members of the world's leading marketing faculty explain the revolutionized world of advertising. The star faculty of the Kellogg School of Management reveal the biggest challenges facing marketers today- including the loss of mass audiences, the decline of broadcast television advertising, and the role of online advertising- and show you how to advertise successfully in this new reality. Based on the latest research and case studies, this book shows you how to find and engage audiences in a chaotic media climate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kellogg on Advertising and Media by Bobby J. Calder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Media Engagement and Advertising Effectiveness

In an era of extreme advertising clutter and consumer avoidance, perhaps no other recent concept has captured more interest from marketers than engagement. This interest is symptomatic of changes in the field. Traditionally, marketers have thought about advertising as a process of translating a brand, expressed as a benefit, a promise to the consumer, a value proposition, or a positioning in the consumer’s mind into a message that is delivered to the consumer through some medium. This advertising will be effective to the extent that the consumer values the brand idea and the message does a good job creatively of communicating the idea. Two things are critical, the quality of the brand and the quality of the message. The media used is more of a tactical matter of achieving the desired reach and frequency against the consumer target group. The present interest in engagement brings something new to this picture.

You can think about engagement in two ways. One way, and the focus here, is on engagement with the advertising medium. If the journalistic or entertainment content of a medium engages consumers, this engagement may affect reactions to the ad. In the past, the medium was thought of as being only a vehicle for the ad, a matter of buying time or space to place the ad to expose the audience to it—a matter of buying eyeballs. But this ignores the fact that the medium provides a context for the ad. If the media content engages consumers, this in turn can make the ad more effective. Another way of thinking about engagement is in terms of engagement with the advertised brand itself. We return to this at the end of the chapter; the focus here is on how engagement with the medium affects advertising effectiveness.

The Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) defines engagement as follows: “Engagement is turning on a prospect to a brand idea enhanced by the surrounding media context” (ARF 2006). This definition highlights the synergy between the brand idea and media context as the key issue for marketers. What is not clear from the definition is what engagement is, as opposed to what it might do.

What Is Engagement?

We all know what engagement feels like. It embodies a sense of involvement. If a person is engaged with a TV program, he or she is connected with it and relates to it. But the concept is hard to pin down beyond this. Ultimately, we need not only to pin it down but also to measure it.

Let’s start with what engagement is not. Our conceptualization of engagement is different from others who often characterize it in ways that we regard as the consequences of engagement. Marc (1966), for example, defines engagement as “how disappointed someone would be if a magazine were no longer published.” Syndicated market research often asks whether a publication is “one of your favorites,” whether a respondent would “recommend it to a friend” or is “attentive.” Many equate engagement with behavioral usage. That is, they define engaged viewers or readers as those who spend substantial time viewing or who read frequently.

While all of these outcomes are important, we argue that they are consequences of engagement rather than engagement itself. It is engagement with a TV program that causes someone to want to watch it, to be attentive to it, to recommend it to a friend, or to be disappointed if it were no longer on the air. Likewise, it is the absence of engagement that will likely cause these outcomes not to occur. But, while these outcomes may reflect engagement, many other things can produce the same outcomes as well. A person may watch a TV program for many reasons. Your spouse may watch it with you to be companionable. Someone in the household gets a magazine so you look at it in spare moments because it is on the coffee table. You like the local newspaper and even recommend it to people moving into the area, but you do not have time to read it yourself. All of these outcomes or consequences are due to something else besides engagement. They should not be confused with engagement. Moreover, to the extent that an outcome is due to engagement, the outcome still does not tell us what engagement actually is.

To think about what engagement really means, come back to engagement as a sense of involvement, of being connected with something. This intuition is essentially correct. It needs elaboration to be useful, but it is correct in that it captures a fundamental insight—engagement comes from experiencing something like a magazine or TV program in a certain way. To understand engagement, we need to be able to understand the experiences consumers have with media content.

The notion of focusing on consumer experiences has itself become a hot topic in marketing, and the question that follows is: What is an experience? A simple answer is that an experience is something that the consumer is conscious of happening in his or her life. The philosopher John Dewey (1934/1980) captured the nuances of experience best:

. . . we have an experience when the material experienced runs its course to fulfillment. Then and then only is it integrated within and demarcated in the general stream of experience from other experiences. . . is so rounded out that its close is a consummation and not a cessation. Such an experience is a whole and carries with it its own individualizing quality and self-sufficiency. It is an experience. (p. 35)

There is always experience, but Dewey points out that much of it is “so slack and discursive that it is not an experience” (p. 40). Much of what we do has, in Dewey’s words, an “anesthetic” quality of merely drifting along. An experience is the sense of doing something in life that leads somewhere. Experiences can be profound but typically they just stand out from the ordinary in the stream of experience.

Experiences are inherently qualitative. That is, they are composed of the stuff of consciousness. They can be described in terms of the thoughts and feelings consumers have about what is happening when they are doing something. As such they are primarily accessible through qualitative research that attempts to “experience the experience” of the consumer (for more on this view of qualitative research, see Calder 1977, 1994, 2000). Thus, we can seek to capture the qualitative experience of, for instance, reading a magazine. This experience will have a holistic or unitary quality but can be broken down into constitutive experiences that have their own holistic quality. As we will see, one such experience for magazines has to do with consumers building social relationships by talking about and sharing what they read with others, the Talking About and Sharing experience. You have undoubtedly had the experience of reading something then using it in conversation with others. To the extent that this experience stands out in the ordinary stream of experience, it constitutes a form of engagement with the magazine.

To further clarify what is unique about the engagement concept, it is useful to distinguish experiences that are closely related to engagement from other experiences. For this, we turn to some ideas from psychology.

Engagement and Experiences

Although much of our work is anchored in qualitative research on experiences, a theoretical model proposed by Columbia University psychologist Tory Higgins (2005, 2006) provides a useful framework for thinking about the relationship of engagement and experience. We follow Higgins and a long tradition in psychology of conceptualizing experience as either approach toward something or avoidance of something. Experiencing something positively means feeling attracted toward it; experiencing something negatively means feeling repulsion away from it. This holistic experience of approach or avoidance is what we want to understand.

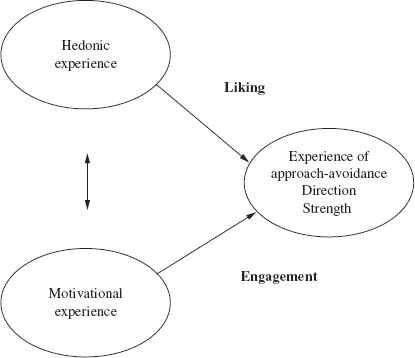

Figure 1.1 presents a model of the approach-avoidance experience. One factor affecting the experience is the hedonic value associated with the object of the experience—what is desirable or undesirable about it, the pleasure/displeasure taken in it. This factor, call it liking, primarily affects the direction of the experience toward approach or toward avoidance. The second factor affecting the experience is engagement. Engagement is thus one of two components of experience, and it is different from the liking component of experience. I may like the local newspaper, but not be particularly engaged with it. Or, I may be engaged with it, but not particularly like it.

Figure 1.1 Engagement as Motivational Experience

Adapted from Higgins (2006).

Engagement stems from the underlying motivational component of the experience. According to Higgins (2006), it is a second source of experience that:

does not involve the hedonic experience of pleasure or pain per se but rather involves the experience of a motivational force to make something happen (experienced as a force of attraction) or make something not happen (experienced as a force of repulsion). Although the hedonic experience and the motivational force experience often are experienced holistically, conceptually they are distinct from one another. (p. 441)

It is thus useful to separate the hedonic side of the experience from the motivational side and to view engagement as the motivational side of the experience.

Media engagement is to be distinguished from liking, that is, the experience of the desirable or undesirable features of a particular magazine, program, or site. In contrast, engagement is about how the magazine or other media product is experienced motivationally in terms of making something happen (or not happen) in the consumer’s life. Note that the magazine experience we described earlier, consumers building social relationships by talking about and sharing what they read with others, is just this sort of experience. It is more about what the content does for the consumer than what the consumer likes about it per se.

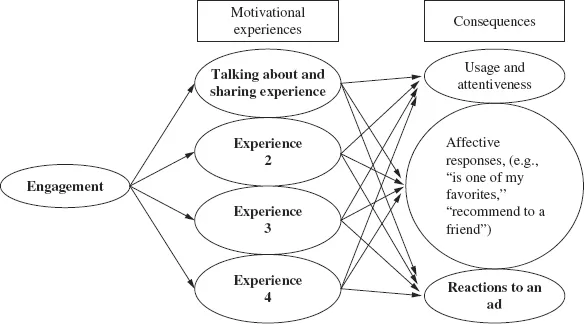

These considerations lead us to view engagement as the sum of the motivational experiences consumers have with the media product. The individual experiences contribute more or less to an overall level of engagement. We therefore analyze engagement in the way shown in Figure 1.2. Separate motivational experiences underlie an overall level of engagement. One of these might be the Talking About and Sharing experience. It is this overall level of media engagement and its constitutive experiences that could affect responses to an ad in the medium. Engagement and experiences may also affect things like usage of the media product, but this should be viewed as a consequence or side effect.

Figure 1.2 Analysis of Engagement and Experiences

Besides providing some conceptual clarity for thinking about engagement, this discussion also points up the reason why media engagement may be important to marketing. All things being equal, it is probably a good idea to place ads in m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Media Engagement and Advertising Effectiveness

- Chapter 2: Making TV a Two-Way Street: Changing Viewer Engagement through Interaction

- Chapter 3: Advertising in the World of New Media

- Chapter 4: Reinvention of TV Advertising

- Chapter 5: Developments in Audience Measurement and Research 123

- Chapter 6: Rethinking Message Strategies: The Difference between Thin and Thick Slicing

- Chapter 7: Managing the Unthinkable: What to Do When a Scandal Hits Your Brand

- Chapter 8: Managing Public Reputation

- Chapter 9: The Contribution of Public Relations in the Future

- Chapter 10: Using THREE I Media in Business-to-Business Marketing

- Chapter 11: Communicating with Customers

- Chapter 12: Changing the Company

- Chapter 13: The Integration of Advertising and Media Content: Ethical and Practical Considerations

- About the Contributors

- Index