- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Commercially used for food flavorings, toiletry products, cosmetics, and perfumes, among others, citrus essential oil has recently been applied physiologically, like for chemoprevention against cancer and in aromatherapy. Citrus Essential Oils: Flavor and Fragrance presents an overview of citrus essential oils, covering the basics, methodology, and applications involved in recent topics of citrus essential oils research. The concepts, analytical methods, and properties of these oils are described and the chapters detail techniques for oil extraction, compositional analysis, functional properties, and industrial uses. This book is an unparalleled resource for food and flavor scientists and chemists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Citrus Essential Oils by Masayoshi Sawamura in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Lebensmittelwissenschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

There are a great number of Citrus varieties widely distributed in the world. It is said that the Citrus genus originated near Assam in India about 30 or 40 million years ago (Iwamasa, 1976). The Citrus fruits that spread to the West migrated to the Middle East and the Mediterranean, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and finally reached America via the West Indies. Others, spreading to the East, migrated to Thailand, Malaysia, China and other Southeast Asian countries. Nowadays, most citrus fruits are grown extensively in the temperate and tropical zones of the northern and southern hemispheres.

Citrus can be propagated and new varieties can be produced by asexual nuclear or chance seedlings, by crossing, and by mutation. In addition to these natural forms of propagation, many new artificially crossed cultivars have been created by Citrus breeders. The classification of this expanding family is complex and is becoming confused. The best-known taxonomies of genus Citrus are those of Swingle (1943) and Tanaka (1969a,b). These two taxonomies differ greatly in the number of species admitted: Swingle identified 16 species, Tanaka 159. Although the basic concept underlying the two taxonomies is different, assignment is almost the same.

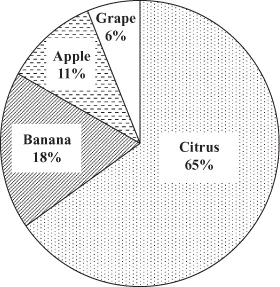

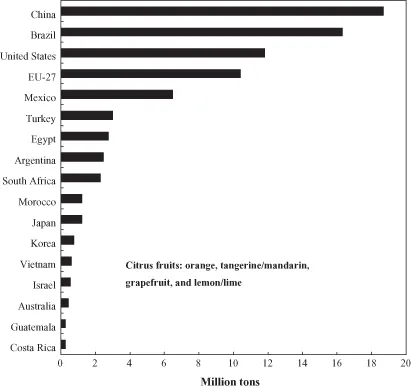

The four major fruit types commercially produced worldwide are citrus fruit, bananas, apples and grapes, followed by pears, peaches, and plums. Citrus fruit finally replaced grapes as the world’s most-produced fruit in 1991. The recent production volume of major fruits is shown in Figure 1.1. The production of citrus fruit accounts for more than 65% of fruits produced. The total world production of citrus fruit in 2008 was about 79.6 million tons; major citrus-producing countries are shown in Figure 1.2. The greatest producer is China, followed by Brazil, the United States, the EU, Mexico, and Turkey. Citrus essential oils have also long been the most popular source of perfume and fragrance essences. There are four reasons why citrus fruit is the most popular fruit in the world: (1) good sour and sweet tastes; (2) pleasant, refreshing aroma; (3) good source of vitamin C; and (4) extensive growing areas worldwide. There are two categories of citrus fruit in terms of food chemistry: sweet citrus fruit, with a sugar/acid ratio of approximately 10, and sour citrus fruit, with a ratio of less than 1. Sweet citrus fruit such as orange, grapefruit, Satsuma mandarin, and pummelo are popular varieties. Sour citrus fruit, on the other hand, such as lemon, lime, bergamot, and yuzu, are less produced, but they are popular in culinary materials such as fruit juice vinegar, and their essential oils are also frequently used in flavoring, cosmetics, and perfume.

Figure 1.1. Worldwide production of major fruits.

Figure 1.2. Major citrus fruits production in 2007.

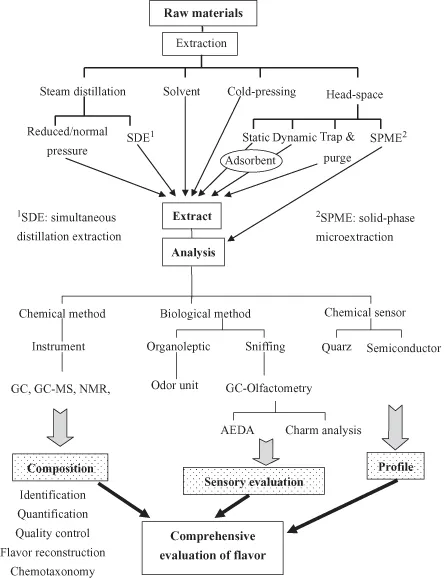

The aim of flavor or aroma research is to determine a fruit’s composition, aroma characteristics, functionality, and industrial or commercial value. The concept of flavor research is outlined in Figure 1.3. First, essential oil is extracted from raw material such as citrus fruits. Then, aroma samples are analyzed using modern instruments, organoleptic procedures, and/or mechanical sensors. The resulting information can give a detailed understanding of the fruit and can be used in further studies of aroma or flavor.

Figure 1.3. Flowchart of flavor research.

The Citrus genus is said to have more than 10,000 varieties and to be produced more than any other kind of fruit in the world. Citrus essential oils account for the largest proportion of commercial natural flavors and fragrances. Essential oils from citrus peel are natural flavoring materials of commercial importance. They have been used in beverages, confectioneries, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and perfumes. The quality, freshness, and uniqueness of citrus oils are major factors contributing to their value and application. Citrus fruits, with their unique and attractive individual aromas, are popularly accepted worldwide, and citrus essential oils are a large and important aroma resource. Quantitative data concerning the volatile components of a number of citrus essential oils (Shaw, 1979; Sawamura, 2000) and their wide commercial use are presented in this book.

The twenty-first century has been referred to as “the era of fragrance.” We live in an atmosphere greatly enriched by aromas and fragrances. Everyday items such as fresh and cooked foods, perfumes, cosmetic and toiletry goods, medicines, and insecticides contain natural or artificial fragrances. Aroma commonly gives us a strong impact in trace amounts. The characteristic odor of an individual substance is composed of roughly a thousand compounds. It is almost impossible to blend every compound of an odor in the exact proportion required to reconstruct the original. It has been determined, however, that there are usually one or two or a few key compounds that can accurately simulate the original odor. One goal of flavor research is to elucidate key aroma compounds by means of a combination of instrumental and organoleptic analyses. Many flavor researchers have tried to find the key aroma compounds of various kinds of citrus. Gas chromatography–olfactomery (GC-O) is a superior method for such studies (Acree, 1993).

Aroma is one of the functional properties of food because aroma compounds stimulate us physically and physiologically (this is referred to as organoleptic effects). A great number of aroma compounds have been identified in a variety of foods to date. Such studies have been a major theme in flavor research. Aroma compounds have a number of properties other than odor production, including antibiotic, deodorant, and blood vessel stimulation. Aromatherapeutic effect also falls into this category. Antioxidants have been investigated most intensively as constituents preventing diseases associated with oxidative damage, and decreasing lipid oxidation during the processing and storage of seafood (Pisano, 1986). Synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), and propyl gallate (PG) are used as food additives to inhibit the actions of toxic and carcinogenic substances (Chang et al., 1977). Natural antioxidants from natural foods such as herbs (Boyd et al., 1993; Pizzocaro et al., 1994), vegetables (Tsushida et al., 1994; Vinson et al., 1998), fruits (Nogata et al., 1996), oilseeds (Medina et al., 1999), spices (Shahidi et al., 1994), green tea (Amarowicz and Shahidi, 1996), and cereals (Hendelman et al., 1999) have been studied, and some of them, such as ascorbate and tocopherols, are currently used in a variety of food products. In recent reports much attention has been given to citrus components, since they present various pharmaceutical activities including anticarcinogenicity, antimutagenicity, antioxidative activity, antiaging, and radical-scavenging (Nogata et al., 1996; Rapisarda et al., 1999; Choi et al., 2000; Sawamura et al., 1999, 2005). Grapefruit oil and lemon extracts have been suggested as effective natural antioxidative compounds (Tokoro, 1997). It has been recently discovered that some foods or foodstuffs serve to inhibit the formation of carcinogens. Essential oils containing terpenoids are well known to have some physiological and pharmaceutical effects, and it is known that citrus essential oils have antimicrobiological (Griffin et al., 1999) and chemopreventive properties (Crowell, 1997; Gould, 1997; Kawaii et al., 1999). The major component of citrus essential oils is terpenes, whose basic structure is isoprenoid (C5H8). The most typical terpenes are limonene, citrus-like odor; γ-terpinene, waxy; terpinolene, green; α-pinene and β-pinene, pine-like. These compounds have been reported to inhibit the growth of cancer cells. One carcinogen, nitrosodimethylamine, which is formed with dimethylamine and nitrite in an acidic condition, has been noted in this regard. Dimethylamine and nitrite are commonly present in meats and vegetables, respectively. It was suggested that some foods or foodstuffs might contain cancer-inhibitory and -preventive compounds as well as cancer-inducing substances (Sawamura et al., 1999, 2005).

Aromatherapy, a medical treatment intended to stimulate or calm the mind, is an applied therapy using the functional properties of essential oils. A variety of vegetable essential oils have been widely used in aromatherapy. Essential oils are extracted from the flowers, leaves, stems, roots, and fruits of various plants and purified for commercial use. Aromatherapy originated in Europe in the eighteenth century and has grown popular in many countries recently, but the most famous essential oil products are still produced in Europe. There are currently seven kinds of commercial citrus essential oils used in aromatherapy: orange, mandarin, lemon, lime, bergamot, grapefruit, and neroli. Yuzu (Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka), a typical Japanese sour citrus fruit, has attracted the interest of aroma therapists over the past ten years. Recently, the effect of yuzu essential oil on the autonomic nervous system has been studied (Sawamura et al., 2009). It is expected that yuzu essential oil will soon be adopted for use in aromatherapy. One obstacle to such application for aromatherapy is that the composition of essential oils changes readily. It has been pointed out that the composition of yuzu (Njoroge et al., 1996) and lemon essential oils (Sawamura et al., 2004) can change considerably under different storage conditions. It is important to carefully consider quality change in commercial essential oil products intended for therapeutic use. This book presents a few attractive studies of functional citrus properties, including aromatherapy.

Recently, food safety or reliability has been a prominent concern, along with food quality. All Japanese foods and products, for example, are controlled under standards such as the European Union regulations regarding food safety and traceability, Japanese Agricultural Standard (JAS), and other regulations governing responsibility to consumers and manufacturers in the United States, Canada, Australia, and England. However, there are few methods for discriminating as to the quality and characteristics of crops from various producing districts. One of the most reliable methods is isotope analysis of food constituents by mass spectrometry. In nature, the isotopes of each element are distributed in a fixed ratio. Plants on the earth first convert solar energy into biochemical energy; the food chain begins with plants. Higher plants fix CO2 by the Calvin-Benson cycle to biosynthesize various organic compounds for their constituents. It is known that the enzyme ribulose-1,5-diphosphate carboxylase differentiates a small mass difference between 12CO2 and 13CO2, when it fixes CO2 in the atmosphere (O’Leary, 1981). This function is referred to as the isotope effect. It is thought that the isotope effect could occur in every enzyme involved in biosynthetic and metabolic pathways. Thus, we can see that this effect should also be applicable to the essential oils comprising terpene compounds. Every species, variety, or strain of a plant has some substantially distinct characteristics. Even among the same cultivars, different growing conditions such as annual atmosphere and moisture, or soil and fertilizers, can bring about small but appreciable differences in composition. Several researchers (Faber et al., 1995; Faulharber et al., 1997; Sawamura et al., 2001; Thao et al., 2007) have tried to distinguish these isotope differences of biological constituents. Some sections of this book discuss methods of verifying the genuineness of food.

Finally, fundamental and academic information about citrus essential oils have contributed to commercial development. In the references section on this chapter, several experts present the reader with attractive topics regarding the wide utilization of citrus essential oils.

REFERENCES

Acree, T.E. (1993). Bioassays for flavor. In: Acree, T.E., Teranishi, R. (eds.), Flavor science. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, pp. 1–18.

Amarowicz, R., Shahidi, F. (1996). A rapid chromatographic method for separation of individual catechins from green tea. Food Research International 29: 71–76.

Boyd, L.C., Green, D.P., Giesbrecht, F.B., King, M.F. (1993). Inhibition of oxidative rancidity in frozen cooked fish flakes by tert-butylhydroquinone and rosemary extract. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 61: 87–93.

Chang, S.S., Ostric-Matijasevic, B., Hsieh, O.A., Chang, C.L. (1977). Natural antioxidants from rosemary and sage. Journal of Food Science 42: 1102–1106.

Choi, H.S., Song, H.S., Ukeda, H., Sawamura, M. (2000). Radical-scavenging activities of citrus essential oils and their components: Detection using 1,1-diphenyl-2- picrylhydrazyl. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

- 2 TECHNIQUES FOR OIL EXTRACTION

- 3 COMPOSITIONAL ANALYSIS

- 4 ENANTIOMERIC AND STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS

- 5 GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY–OLFACTOMETRY AND AROMA-ACTIVE COMPONENTS IN CITRUS ESSENTIAL OILS

- 6 FUNCTIONAL PROPERTIES

- 7 AROMATHERAPY

- 8 INDUSTRIAL VIEW

- Index