![]()

Chapter 1

The Claw Will Take Your Money

“10 − 2 = 8”

“We live in a great and free country,” I told my 8-year-old son Kevin, as we sat eye-to-eye at the kitchen table one day in what I hoped was one of those father/son bonding moments. I continued by explaining that we are so prosperous because of a beautiful thing called capitalism. And that one of the benefits of capitalism is that if we don’t spend all of the money we have, we can invest it in companies. “Our money will actually grow,” I said, miming a tree growing with all the dramatic flair a CPA can muster.

“How fast will it grow?” asked Kevin. I estimated that owning stocks has resulted in about a 10 percent annual growth, meaning that every dollar invested would be worth $2 in 7 years, $4 in 14 years and almost $7.50 in 21 years.

Kevin was amazed and excitedly blurted out, “If I invest all the money from my grandparents, I can buy anything I want when I’m older!” I’d hooked him.

At this point, I had to clue him in on one more thing. I explained that in order to see their money grow, most people who invest pay about 2 percent per year to helpers. That means instead of $7.50 in 21 years, he’d only have about $5.00, I told him.

“What do the helpers do?” asked Kevin.

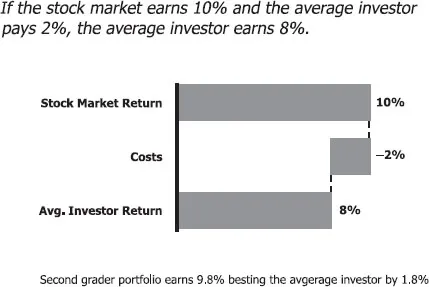

The answer, of course, was absolutely nothing. If the stock market earned 10 percent and the average investor paid Wall Street 2 percent, that left only 8 percent for investors. This is simple arithmetic any second grader can do.

Upon hearing this news, Kevin looked a little less excited. If there’s one thing every second grader has a clear grasp of, it’s what is and isn’t fair. Being a second grader and therefore one of the “go-to” guys in determining fairness, Kevin decreed, “That doesn’t sound fair.” He astutely noted that if he didn’t have to pay the 2 percent, then he could keep the entire 10 percent, affirming we really were from the same gene pool.

I then explained to him that we always have to pay something to invest, but we could cut that 2 percent down to 0.2 percent. Realizing that he would get to keep nearly the entire 10 percent that his money would grow, Kevin perked up again—although he still wondered aloud, “Why do people pay two percent when they don’t have to? That sounds like ‘the claw’ to me.”

Kevin was referring to an arcade machine where you put a quarter in and direct the claw scooper over a bunch of prizes in the hopes that it will pick up the prize you’re aiming for. (See Exhibit 1.1.) After all, snagging some cool stuffed animal for only a quarter was virtually irresistible. For a few weeks, Kevin would spend a portion of his allowance trying for his grand prize. He got nothing. After feeding it a few dollars, Kevin had an aha! moment. “This game is a ripoff!”1 he said, as he came to the painful realization that he wasn’t going to get that prize he had repeatedly aimed for. He hasn’t played the claw game since.

I’ve often wondered why adults keep feeding quarters to Wall Street. In response to his question, I could have launched into some scaled-down explanation of the efficient market hypothesis, but instead I just thought of Charley Ellis’s timeless investing book, Winning the Loser’s Game (McGraw-Hill, 3rd ed., 1998) and recited the book’s famous message (with a small tweak to appeal to Kevin):

The Common Sense of Kevin’s Math

If you have any investing experience, you may be thinking that I’ve just skipped the whole debate between active and passive investing.

Active management refers to the use of a human element—such as a single manager, co-managers, or a team of managers—to actively manage a stock portfolio. Active managers rely on analytical research, forecasts, and their own judgment and experience in making investment decisions on what securities to buy, hold, and sell. Warren Buffett and Bill Miller, for example, have long-term track records of beating the market.

Passive management is an investment theory that states that it is impossible to “beat the market” because stock market efficiency causes existing share prices to always incorporate and reflect all relevant information. People who ascribe to this are generally followers of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). According to the EMH, this means that stocks always trade at their estimated fair value on stock exchanges, making luck responsible for investors either purchasing undervalued stocks or selling stocks for inflated prices. Burton Malkiel’s famous book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street, advocates passive management.

Can I just make the assumption that the expenses associated with active investing (the 2 percent I mentioned earlier) don’t add any value? As you’ll see, we don’t actually need to explore this active-versus-passive debate, because the answer is merely dependent on second-grade arithmetic. There are countless papers, books, and experts all around us that claim to beat the market. After all, they state, it’s not about the lowest cost; it’s about getting the highest return. The arguments for active management have two things in common:

1. They are emotionally appealing.

2. They fly in the face of simple mathematics.

Sticking with the theme of simple math, let’s examine the simple 10 − 2 = 8 equation by looking at the U.S. stock market.

The U.S. Stock Market

The U.S. stock market is comprised of roughly 7,000 individual stocks with a total value (market capitalization) of roughly $17.5 trillion. Wall Street revenue from the services it provides is roughly $350 billion2 (which just happens to be about the size of the U.S. deficit3). The Wall Street take is about 2 percent of the value of the U.S. market.

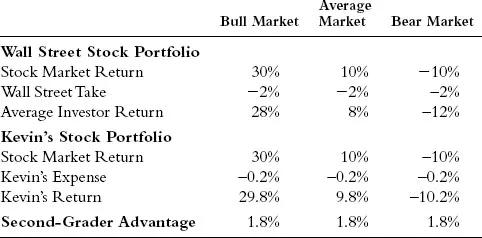

While Kevin won’t have the lessons to construct the whole portfolio until Chapter 2, let’s take a look at how Kevin’s total U.S. stock index fund will perform in a year with a bull market return, average market return, and bear market return with an expense ratio of 0.2 percent, and compare it to the professionally managed Wall Street U.S. portfolio. Exhibit 1.2 illustrates the return of the Wall Street portfolio versus Kevin’s portfolio in an up year in the market.

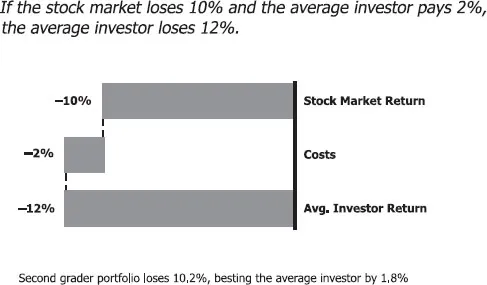

Kevin also earned the 10 percent of the U.S. market but only paid 0.2 percent in expenses (to Vanguard). Thus, he earned 9.8 percent, which is a full 1.8 percent more than the average investor earned. Will this work in a down market as well? The answer is an unequivocal yes! In a year where the stock market loses 10 percent, the average investor will lose 12 percent. Because Kevin pays 1.8 percent less than the average investor, he again earns 1.8 percent more. See Exhibit 1.3.

What does this extra 1.8 percent in annual earnings mean? Let me put it a couple of different ways:

1. At an 8 percent annual return, Kevin’s dollar invested would be worth over $21 in 40 years, when he’s his old man’s age. At 9.8 percent, however, it will be worth over $42. In other words, that extra 1.8 percent of annual return nearly doubles his portfolio’s final value.

2. We adults may not have as many years to benefit from the power of compounding as Kevin does, but I’ve found that my average clients can reach their financial goals by a year sooner for every 0.25 percent they can lower expenses in their portfolio. This means that 1.8 percent is worth about seven years to us adults. And, as you will soon learn, most adults can boost return by far more than this 1.8 percent, thus reaching our goals that much sooner.

An important item to note is that Kevin’s advantage isn’t dependent on whether the market goes up or down; it’s dependent only on the difference in expenses that he is paying versus the Wall Street average expense.

A second important item is that this argument of simple arithmetic is not dependent on the efficient market hypothesis. It doesn’t matter one iota whether stocks are efficiently priced or wildly misvalued. The only thing that matters is that all investors—you and me—cannot be above average and that 10 − 2 must equal 8! So, forget the debate about the efficient market hypothesis and remember the second-grader hypothesis that 10 − 2 = 8. Of course, this is adapted from Jack Bogle’s cost matters hypothesis.

The International Stock Market

The same simple arithmetic of investing that worked for the U.S. stock market must work in the international stock markets as well, right? International markets have their versions of helpers who get their take of the action. The argument that international markets are less efficient than the U.S. market happens to fly in the face of contrary data. According to Morningstar, the Vanguard Total U.S. Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) has bested 77 percent of its peers over the past five years. That’s pretty impressive, but the Vanguard Total International Index Fund (VGTSX) bested 86 percent of its peers.4

Granted, we could debate the point of whether international markets are less efficient, but the argument also happens to be irrelevant. The world stock market has a total value of roughly $40 trillion and, while coming up with the total fees charged by the worldwide helpers is more difficult, there is no reason to believe it should be any less than 2 percent. So, the concept remains the same. If Kevin owns the international markets at the lowest costs, he must beat the average professionally managed global portfolio that has higher costs. See Exhibit 1.4.

The Bond Market

I’ll explain a bit later in the book why everyone needs some fixed-income investments (bonds)—even a second grader with a very long investment horizon. For now, let me say that every argument made for keeping fees low in the stock market applies just as stringently in the bond market. That is, the average bond investor will get the average bond return before expenses. Thus, owning the entire bond market at the lowest costs must yield a return that beats the more expensive professionally managed portfolios.

The Arithmetic of Active Management

As much as I’d like to claim that this simple mathematics is the brainchild of Kevin’s and my brilliance, it isn’t. A fellow by the name of William Sharpe, the winner of the 1990 Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote a famous paper called “The Arithmetic of Active Management.”5 In it Sharpe states, “Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs.” He also notes that the proof is “embarrassingly simple.”

It’s simple enough that an 8-year-old can understand it, yet somehow very difficult for us adults to grasp. We adults seem to buy into the expectation that our active manager is really good, so we will be among the few who beat the market. Of course, if my manager is so good that he can beat all the other managers, then why isn’t he working for the billion-dollar investors?

Can My Professional Really Beat Yours?

One reason that ignoring simple mathematics seems preferable to most adults is that we strongly resist thinking of ourselves as average. And if by some wild chance we are average, can’t we just find a money manager who is above average? Whether we are in the casino or playing the stock market, it’s virtually impossible to resist thinking of ourselves as a Doyle Brunson or a Warren Buffett.

It se...