eBook - ePub

The Science of Reading

A Handbook

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Science of Reading

A Handbook

About this book

The Science of Reading: A Handbook brings together state-of-the-art reviews of reading research from leading names in the field, to create a highly authoritative, multidisciplinary overview of contemporary knowledge about reading and related skills.

- Provides comprehensive coverage of the subject, including theoretical approaches, reading processes, stage models of reading, cross-linguistic studies of reading, reading difficulties, the biology of reading, and reading instruction

- Divided into seven sections:Word Recognition Processes in Reading; Learning to Read and Spell; Reading Comprehension; Reading in Different Languages; Disorders of Reading and Spelling; Biological Bases of Reading; Teaching Reading

- Edited by well-respected senior figures in the field

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Reading by Margaret J. Snowling, Charles Hulme, Margaret J. Snowling,Charles Hulme in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Word Recognition Processes in Reading

Editorial Part I

Word recognition is the foundation of reading; all other processes are dependent on it. If word recognition processes do not operate fluently and efficiently, reading will be at best highly inefficient. The study of word recognition processes is one of the oldest areas of research in the whole of experimental psychology (Cattell, 1886). The chapters in this section of the Handbook present an overview of current theories, methods, and findings in the study of word recognition processes in reading.

What do we mean by recognition here? Recognition involves accessing information stored in memory. In the case of visual word recognition this typically involves retrieving information about a word’s spoken form and meaning from its printed form. The first two chapters, by Coltheart and Plaut, outline the two most influential theoretical frameworks for studies of visual word recognition.

Coltheart outlines the history and evolution of dual-route models of reading aloud (i.e., how the pronunciation of a printed word is generated). These dual-route models posit that there are two routes from print to speech: a lexical and nonlexical route. Broadly the lexical route involves looking up the pronunciation of a word stored in a lexicon or mental dictionary. In contrast, the nonlexical route involves translating the graphemes (letters or letter groups) into phonemes and assembling the pronunciation of a word from this sequence of phonemes. Such a process should work just as well for nonwords as for words, just so long as the word follows the spelling pattern of the language (a nonlexical reading of YACHT, will not yield the pronunciation for a kind of boat with a sail on it). This idea is embodied in an explicit computational model (the DRC model) that Coltheart describes in detail. It may be worth emphasizing that this highly influential model is a model of how adults read aloud; it is not concerned with how the knowledge allowing this to happen is acquired. A major focus of the model is how different disorders of reading aloud, which arise after brain damage in adults, can be accounted for.

Plaut gives an overview of a different class of models of reading aloud that employ connectionist architectures (models that learn to pronounce words by training associations between distributed representations of orthography and phonology). One particularly influential model of this type is the so-called triangle model (Plaut, McClelland, Seidenberg, & Patterson, 1996; Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989). This model abandons the distinction between a lexical and nonlexical procedure for translating visual words into pronunciations; instead the same mechanism is used to convert words and nonwords into pronunciations, based on patterns of connections between orthographic inputs and phonological outputs. One other critical difference between the triangle model and the DRC model is that the triangle model explicitly embodies a learning procedure and thus can be considered a model of both adult reading and reading development. It is clear that these are very different conceptions of how the mind reads single words. Both approaches deal with a wide range of evidence. Arguably, the DRC model is more successful in dealing with the detailed form of reading impairments observed after brain damage in adults, while the ability to think about development and adult performance together in the triangle model is a considerable attraction. There is no doubt that differences between these models will be a source of intense interest in the coming years.

Lupker’s chapter moves on to review a huge body of experimental evidence concerned with how adults recognize printed words. Many of these experiments investigate what is a remarkably rapid and accurate process in most adults, by measuring reaction time, or by impairing performance by using masking (preventing participants from seeing a word clearly by superimposing another stimulus immediately after the word has been presented). Any complete model of word recognition ultimately will have many phenomena from such experiments to explain. These include the fact that people perceive letters more efficiently when they are embedded in words, that high-frequency (i.e., more familiar) words are recognized easier than less familiar words, and that recognition of words is influenced by previously presented words (seeing a prior word that is related in form or meaning helps us to recognize a word that follows it). One conclusion that emerges powerfully from Lupker’s review is the need for interactive models in which activation of orthographic and phonological information reciprocally influence each other. This is an issue that Van Orden and Kloos take up in detail, presenting a wealth of evidence that converges on the idea that there is intimate and perpetual interaction between representations of orthography and phonology (spelling and sound) during the process of recognizing a printed word.

Moving on from the recognition of isolated words, Rayner, Juhasz, and Pollatsek discuss eye movements in reading. Eye movements provide a fascinating window on how word recognition processes operate in the more natural context of reading continuous text. It appears that the pattern of eye movements in reading is heavily influenced by the cognitive processes subserving both word recognition and text comprehension. The majority of words in text are directly fixated (usually somewhere in the first half of the word). For readers of English the area of text processed during a fixation (the perceptual span) is about 3 or 4 letters to the left of fixation and some 14 or 15 letters to the right of fixation. This limit seems to be a basic one determined by acuity limitations, and useful information about letter identity is extracted only from a smaller area, perhaps 7 or 8 letters to the right of the fixation point. It appears that only short, frequent, or highly predictable words are identified prior to being fixated (so that they can be skipped). However, partial information (about a word’s orthography and phonology but typically not its meaning) about the word following the fixation point often is extracted and combined with information subsequently extracted when the word is directly fixated. These studies are consistent with the view that the speed and efficiency of word recognition processes (as well as higher-level text-based processes) place fundamental constraints on how quickly even skilled readers read text.

Arguably the central question in the study of word recognition in reading is the role of phonology. All of the chapters in Part I address this issue explicitly. It appears that a consensus has been reached: phonological coding is central to word recognition, though opinions are divided on many details of how phonology is accessed and its possible importance in providing access to semantic information.

1

Modeling Reading: The Dual-Route Approach

Reading is information-processing: transforming print to speech, or print to meaning. Anyone who has successfully learned to read has acquired a mental information-processing system that can accomplish such transformations. If we are to understand reading, we will have to understand the nature of that system. What are its individual information-processing components? What are the pathways of communication between these components?

Most research on reading since 1970 has investigated reading aloud and so sought to learn about the parts of the reading system that are particularly involved in transforming print to speech. A broad theoretical consensus has been reached: whether theories are connectionist (e.g., Seidenberg & McClelland, 1989; Plaut, this volume) or nonconnectionist (e.g., Coltheart, Curtis, Atkins & Haller, 1993), it is agreed that within the reading system there are two different procedures accomplishing this transformation – there are dual routes from print to speech. (The distinction between connectionist and nonconnectionist theories of cognition is discussed later in this chapter.)

In the Beginning…

The dual-route conception of reading seems first to have been enunciated by de Saussure (1922; translated 1983, p. 34):

there is also the question of reading. We read in two ways; the new or unknown word is scanned letter after letter, but a common or familiar word is taken in at a glance, without bothering about the individual letters: its visual shape functions like an ideogram.

However, it was not until the 1970s that this conception achieved wide currency. A clear and explicit expression of the dual-route idea was offered by Forster and Chambers (1973):

The pronunciation of a visually presented word involves assigning to a sequence of letters some kind of acoustic or articulatory coding. There are presumably two alternative ways in which this coding can be assigned. First, the pronunciation could be computed by application of a set of grapheme–phoneme rules, or letter-sound correspondence rules. This coding can be carried out independently of any consideration of the meaning or familiarity of the letter sequence, as in the pronunciation of previously unencountered sequences, such as flitch, mantiness and streep. Alternatively, the pronunciation may be determined by searching long-term memory for stored information about how to pronounce familiar letter sequences, obtaining the necessary information by a direct dictionary look-up, instead of rule application. Obviously, this procedure would work only for familiar words. (Forster & Chambers, 1973, p. 627)

Subjects always begin computing pronunciations from scratch at the same time as they begin lexical search. Whichever process is completed first controls the output generated. (Forster & Chambers, 1973, p. 632)

In the same year, Marshall and Newcombe (1973) advanced a similar idea within a box-and arrow diagram. The text of their paper indicates that one of the routes in that model consists of reading “via putative grapheme–phoneme correspondence rules” (Marshall & Newcombe, 1973, p. 191). Since the other route in the model they proposed involves reading via semantics, and is thus available only for familiar words, their conception would seem to have been exactly the same as that of Forster and Chambers (1973).

This idea spread rapidly:

We can… distinguish between an orthographic mechanism, which makes use of such general and productive relationships between letter patterns and sounds as exist, and a lexical mechanism, which relies instead upon specific knowledge of pronunciations of particular words or morphemes, that is, a lexicon of pronunciations (if not meanings as well). (Baron & Strawson, 1976, p. 386)

It seems that both of the mechanisms we have suggested, the orthographic and lexical mechanisms, are used for pronouncing printed words. (Baron & Strawson, 1976, p. 391)

Naming can be accomplished either by orthographic-phonemic translation, or by reference to the internal lexicon. (Frederiksen & Kroll, 1976, p. 378)

In these first explications of the dual route idea, a contrast was typically drawn between words (which can be read by the lexical route) and nonwords (which cannot, and so require the nonlexical route). Baron and Strawson (1976) were the first to see that, within the context of dual-route models, this is not quite the right contrast to be making (at least for English):

The main idea behind Experiment 1 was to compare the times taken to read three different kinds of stimuli: (a) regular words, which follow the “rules” of English orthography, (b) exception words, which break these rules, and (c) nonsense words, which can only be pronounced by the rules, since they are not words. (Baron & Strawson, 1976, p. 387)

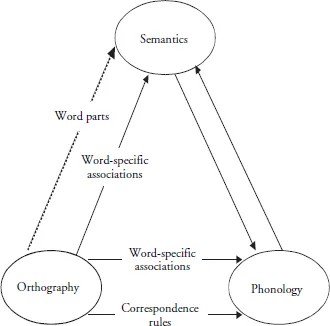

Figure 1.1 An architecture of the reading system (redrawn from Baron, 1977).

Baron (1977) was the first to express these ideas in a completely explicit box-and-arrow model of reading, which is shown in figure 1.1. This model has some remarkably modern features: for example, it has a lexical-nonsemantic route for reading aloud (a route that is available only for words yet does not proceed via the semantic system) and it envisages the possibility of a route from orthography to semantics that uses word parts (Baron had in mind prefixes and suffixes here) as well as one that uses whole words.

Even more importantly, the diagram in figure 1.1 involves two different uses of the dual-route conception. The work previously cited in this chapter all concerned a dualroute account of reading aloud; but Baron’s model also offered a dual-route account of reading comprehension:

we may get from print to meaning either directly – as when we use pictures or maps, and possibly when we read a sentence like I saw the son – or indirectly, through sound, as when we first read a word we have only heard before. (Baron, 1977, p. 176)

Two different strategies are available to readers of English for identifying a printed word. The phonemic strategy involves first translating the word into a full phonemic (auditory and/or articulatory) representation, and then using this representation to retrieve the meaning of the word. This second step relies on the same knowledge used in identifying words in spoken language. This strategy must be used when we encounter for the first time a word we have heard but not seen. The visual strategy involves using the visual information itself (or possibly some derivative of it which is not formally equivalent to overt pronunciation) to retrieve the meaning. It must be used to distinguish homophones when the context is insufficient, for example, in the sentence, “Give me a pair (pear).” (Baron & McKillop, 1975, p. 91)

The dual-route theory of reading aloud and the dual-route theory of reading comprehension are logically independent: the correctness of one says nothing about the correctness of the other. Further discussion of these two dual-route theories may be found in Coltheart (2000). The present chapter considers just the dual-route approach to reading aloud.

A final point worth making re Baron’s chapter has to do with the analogy he used to illustrate why two routes might be better than one (even when one is imperfect – the nonlexical route with irregular words, for example):

A third – and to me most satisfying – explanation of the use of the indirect path… is that it is used in parallel with the direct path. If this is the case, we can expect it to be useful even if it is usually slower than the direct path in providing information about meaning. If we imagine the two paths as hoses that can be used to fill up a bucket with information about meaning, we can see that addition of a second hose can speed up filling the bucket even if it provides less water than the first. (Baron, 1977, p. 203)

An analogy commonly used to describe the relationship between the two routes in dual-route models has been the horse race: the lexical and nonlexical routes race, and whichever finishes first is responsible for output. But this analogy is wrong. In the reading aloud of irregular words, on those occasions where the nonlexical route wins, according to the horse race analogy the response will be wrong: it will be a regularization error. But what is typically seen in experiments on the regularity effect in reading aloud is that responses to irregular words are correct but slow. The horse race analogy cannot capture that typical result, whereas Baron’s hose-and-bucket analogy can. The latter analogy is equally apt in the case of the dual-route model of reading comprehension.

“Lexical” and “Nonlexical” Reading Routes

This use of the terms “lexical” and “nonlexical” for referring to the two reading routes seems to have originated with Coltheart (1980). Reading via the lexical route involves looking up a word in a mental lexicon containing knowledge about the spellings and pronunciations of letter strings that are real words (and so are present in the lexicon); reading via the nonlexical route makes no reference to this lexicon, but instead involves making use of rules relating segments of orthography to segments of phonology. The quotation from de Saussure with which this chapter began suggested that the orthographic segments used by the nonlexical route are single letters, but, as discussed by Coltheart (1978), that cannot be right, since in most alphabetically written languages single phonemes are frequently represented by sequences of letters rather than single letters. Coltheart (1978) used the term “grapheme” to refer to any letter or letter sequence that represents a single phoneme, so that TH and IGH are the two graphemes of the two-phoneme word THIGH. He suggested that the rules used by the nonlexical reading route are, specifically, grapheme–phoneme correspondence rules such as TH → /θ/ and IGH → /ai/.

Phenomena Explained via the Dual-Route Model

This model was meant to explain data not only from normal reading, but also facts about disorders of reading, both acquired and developmental.

Reaction times in reading-aloud experiments are longer for irregular words than regular words, and the dual-route model attributed this to that fact that the two routes generate conflicting information at the phoneme level when a word is irregular, but not when a word is regular: resolution of that conflict takes time, and that is responsible for the regularity effect in speeded reading aloud. Frequency effects on reading aloud were explained by proposing that access to entries for high-frequency words in the mental lexicon was faster than access for low-frequency words. From that it follows, according to the dualroute model, that low-frequency words will show a larger regularity effect, since lexical processing will be relatively slow for such words and there will be more time for the conflicting information from the nonlexical route to affect reading; and this interaction of frequency with regularity was observed.

Suppose brain damage in a previously literate person selectively impaired the operation of the lexical route for reading aloud while leaving the nonlexical route intact. What would such a person’s reading be like? Well, nonwords and regular words would still be read with normal accuracy because the nonlexical route can do this job; but irregular words will suffer, because for correct reading they require the lexical route. If it fails with an irregular word, then the response will just come from the nonlexical route, and so will be wrong: island will be read as “iz-land,” yacht to rhyme with “matched,” and have to rhyme with “cave.” Exactly this pattern is seen in some people whose reading has been impaired by brain damage; it is called surface dyslexia, and two particularly clear cases are those reported by McCarthy and Warrington (1986) and Behrmann and Bub (1992). The occurrence of surface dyslexia is good evidence that the reading system contains lexical and nonlexical routes for reading aloud, since this reading disorder is exactly what would be expected if the lexical route is damaged and the nonlexical route is spared.

Suppose instead that brain damage in a previously literate person selectively impaired the operation of the nonlexical route for reading aloud while leaving the lexical route intact. What would such a person’s reading be like? Well, irregular words and regular words would still be read with normal accuracy because the lexical route can do this job; but nonwords will suffer, because for correct reading they require the nonlexical route. Exactly this pattern – good reading of words with poor reading of nonwords – is seen in some people whose reading has been impaired by brain damage; it is called phonological dyslexia (see Coltheart, 1996, for a review of such studies). This too is good evidence for a dual-route conception of the reading system.

The reading disorders just discussed are called acquired dyslexias because they are acquired as a result of brain damage in people who were previously literate. The term “developmental dyslexia,” in contrast, refers to people who have had difficulty in learning to read in the first place, and have never attained a normal level of reading skill. Just as brain damage can selectively affect the lexical or the nonlexical reading route, perhaps also learning these two routes is subject to such selective influence. This is so. There are children who are very poor for their age at reading irregular words but normal for their age at reading regular words (e.g., Castles & Coltheart, 1996); this is developmental surface dyslexia. And there are children who are very poor for their age at reading nonwords but normal for their age at reading regular words and irregular words (e.g., Stothard, Snowling, & Hulme, 1996); this is developmental phonological dyslexia. Since it appears that difficulties in learning just the lexical and or just the nonlexical route can be observed, these different patterns of developmental dyslexia are also good evidence for the dual-route model of reading.

Computational Modeling of Reading

We have seen that the dual-route conception, applied both to reading aloud and to reading comprehension, was well established by the mid-1970s. A major next step in the study of reading was computational modeling.

A computational model of some form of cognitive processing is a computer program which not only executes that particular form of processing, but does so in a way that the modeler believes to be also the way in which human beings perform the cognitive task in question. Various virtues of computational modeling are g...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- PART I: Word Recognition Processes in Reading

- PART II: Learning to Read and Spell

- PART III: Reading Comprehension

- PART IV: Reading in Different Languages

- PART V: Disorders of Reading and Spelling

- PART VI: The Biological Bases of Reading

- PART VII: Teaching Reading

- Glossary of Terms

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index