![]()

1 Dual-Route Theories of Reading Aloud

Max Coltheart

At the 1971 meeting of the International Neuropsychology Symposium in Engelberg, Switzerland, John Marshall and Freda Newcombe described six people who had suffered brain damage that had affected their ability to read – six case of acquired dyslexia. These six people fell into three different categories, since the pattern of reading symptoms they showed differed qualitatively as a function of which category they were assigned to. The three categories of acquired dyslexia were named ‘deep dyslexia’, ‘surface dyslexia’ and ‘visual dyslexia’.

The publication of this work two years later (Marshall & Newcombe, 1973) initiated a major research field – the cognitive neuropsychology of reading. It did this not so much because it emphasized that there are different subtypes of acquired dyslexia – though this was a very important thing to demonstrate – but because the authors offered an explicit information-processing model of reading aloud and suggested how each of the three forms of acquired dyslexia could be understood as generated by three different patterns of impairment of that model.

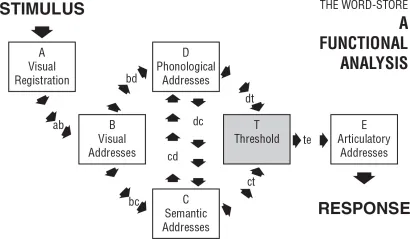

Their model is shown in Figure 1.1. It is a dual-route model of reading aloud (though Marshall and Newcombe did not use the term ‘dual route’) because there are two processing routes from print (the stimulus) to speech (the response). One route is via Visual Addresses through Semantic Addresses to articulation. This route can only be used with those letter strings that possess semantic addresses – that is, only with words. The route cannot produce reading-aloud responses for nonwords.

Figure 1.1 The dual-route model of reading proposed by Marshall and Newcombe (1973). With kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Figure 1 of Marshall, J.C., & Newcombe, F. (1973). Patterns of paralexia: A psycholinguistic approach. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 2, 175–199.

How Marshall and Newcombe conceived of the second route for reading aloud (the A→B→D→T→F route) is not entirely clear from the Figure 1.1 diagram; but it is perfectly clear from their paper: ‘If . . . as a consequence of brain damage, the functional pathway bc (Fig. 1) is usually unavailable, the subject will have no option other than attempting to read via putative grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules (pathway bd)’ (Marshall & Newcombe, 1973, p. 191).

A processing route that translates print to speech by application of grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules will be able to read letter strings that are not words. However, by definition it will fail for letter strings whose pronunciations differs from the pronunciations generated by the grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules of the language: the so-called irregular or exception words1 of the language. Marshall and Newcombe did not quite make this point about irregular words and the second reading route, but they clearly had it in mind: ‘a recent formalism . . . proposes 166 correspondence rules in an analysis of children’s reading books. These rules only account for 90% of the data, leaving 10% of quite common words provided with an incorrect pronunciation’ (Marshall & Newcombe, 1973, p. 191).

The dual-route model of reading aloud was proposed independently in the same year by Forster and Chambers (1973).

The pronunciation of a visually-presented word involves assigning to a sequence of letters some kind of acoustic or articulatory coding. There are presumably two alternative ways in which this coding can be assigned. First, the pronunciation could be computed by application of a set of grapheme-phoneme or letter-sound correspondence rules. This coding can be carried out independently of any consideration of the meaning or familiarity of the letter sequence, as in the pronunciation of previously unencountered sequences, such as flitch, mantiness, and streep. Alternatively, the pronunciation may be determined by searching long-term memory for stored information about how to pronounce familiar letter sequences, obtaining the necessary information by a direct dictionary look-up, instead of rule-application. Obviously this procedure would only work for familiar words.

(Forster & Chambers, 1973, p. 627)

These authors did not raise the issue of irregular words (words whose pronunciations disobey grapheme-phoneme rules and so could not be correctly read aloud using the grapheme-phoneme rule route).

After this dual introduction of the dual-route model of reading aloud, the idea spread rapidly, for example:

We can . . . distinguish between an orthographic mechanism, which makes use of such general and productive relationships between letter patterns and sounds as exist, and a lexical mechanism, which relies instead upon specific knowledge of pronunciations of particular words or morphemes, that is, a lexicon of pronunciations (if not meanings as well) . . . It seems that both of the mechanisms we have suggested, the orthographic and lexical mechanisms, are used for pronouncing printed words.

(Baron & Strawson, 1976, pp. 386, 391)

Naming can be accomplished either by orthographic-phonemic translation, or by reference to the internal lexicon.

(Frederiksen & Kroll, 1976, p. 378)

Given the central role played by the concept of irregularity of grapheme-phoneme correspondence in the dual-route approach, what was clearly needed next was empirical investigation of the influence of such irregularity on the reading aloud of words. If regular words (those which obey the correspondence rules) can be read aloud correctly via the rule route and also by the dictionary lookup route, while irregular words can only be read aloud correctly by the dictionary lookup route, one might expect this to result in reading-aloud latencies being shorter for regular words than for irregular words. This was first investigated by Baron and Strawson (1976), who did indeed find that reading aloud was slower for irregular words than for regular words.

At this point, it is necessary to say something more, by way of definition, about the concept of regularity and also about another concept, consistency, which also became important in reading research from the late 1970s onwards.

The Concepts of Regularity and Consistency

To produce perfectly clear terminology here, we need some definitions. To define the irregular/regular distinction, we first need to define the term grapheme. Relationships between spellings and pronunciations are often referred to as being governed by letter–sound rules, but that’s incorrect. The word THIGH has five letters. So if it were literally letters that were being translated to sounds (phonemes), this word would have five phonemes; but it doesn’t, it has only two. So the orthographic units that are being mapped onto phonemes here are not letters: they are orthographic units that are the written representations of phonemes. The definition of ‘grapheme’ is: the written representation of a phoneme. Thus the graphemes of THIGH are <TH> and <IGH>. Hence the correct term for the mappings of spellings to sounds is ‘grapheme-phoneme correspondences’ (GPCs). And the translation of the letter sequence THIGH to the grapheme sequence <TH> + <IGH> is referred to as ‘graphemic parsing’.

For most of the graphemes of English, the grapheme can correspond to different phonemes in different words: consider the grapheme <OO> in BLOOD, GOOD, and FOOD, for example. If there is a set of GPC rules for English, what phoneme is to be associated with the grapheme <OO> in this set of rules? A commonly adopted approach is to choose, as the phoneme for any particular grapheme, the phoneme that is associated with that grapheme in the largest number of words containing that grapheme. For <OO>, this is the phoneme /u:/, as in FOOD. So the GPC rule for <OO> is <OO> → /u:/. Alternative approaches are possible. For example, instead of using the type frequency of phonemes to decide what phoneme should be associated with a particular grapheme one could use token frequency. Of the words containing the grapheme <TH>, there are more words which have the unvoiced phoneme as in THICK than have the voiced phoneme as in THAT, but the summed frequency of the words which have the unvoiced phoneme is lower than the summed frequency of the words than have the voiced phoneme. So the GPC for the grapheme <TH> would have the unvoiced phoneme if type frequency were used as the criterion, but the voiced phoneme if token frequency were used as the criterion.

Once a set of GPC rules is assembled in this way for all the graphemes of English, one can inspect each word of English to determine whether application of this set of rules generates its pronunciation correctly. When this does occur, the word is classified as regular (e.g. FOOD). When in contrast the rule-generated pronunciation of a word differs from the word’s dictionary pronunciation (as in e.g. BLOOD or GOOD), the word is classified as irregular. Note that this means that one cannot speak of nonwords as regular or irregular, since nonwords don’t have dictionary pronunciations; so the terms ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ apply only to words. And these terms denote an all-or-none distinction: on this approach, there are not gradations of regularity (unlike consistency, which, as we will see shortly, can be thought of as graded).

Next we need to define the consistent/inconsistent distinction. Here again we need first to define a particular term: the term body. The body of a pronounceable monosyllabic letter string is the sequence of letters from the initial vowel to the end of the string. A pronounceable letter string (which may be a word or a nonword) is body-consistent if all the words that contain that body rhyme i.e. have the same pronunciation of that body. If in the set of words containing that body there is more than one pronunciation of the body, any letter-string containing that body is body-inconsistent. The concept of consistency can be applied to orthographic components other than the body (e.g. the orthographic onset), but this has rarely been done. So almost all work on consistency has been work on body-consistency, and so when I use the term ‘consistency’ I will just be referring to body-consistency, and will not consider other kinds of consistency in this chapter.

One can treat the consistent/inconsistent distinction as all-or-none; or one can think of degrees of consistency, as measured, for example, by the proportion of words containing a particular body that share the same pronunciation of that body.

Glushko’s Work

The next important event in the history of the dual-route theory of reading was the paper by Glushko (1979). Glushko discussed both of the distinctions that I have just defined: irregular2 versus regular, and inconsistent versus consistent. He would have liked there to be only three categories here: irregular, regular-inconsistent and regular-consistent. But that would amount to the claim that there are no irregular words that are consistent and as he says (Glushko, 1979, p. 684, footnote 3) this is not the case: he acknowledges, with evident disappointment, that there are irregular words which must be classified as consistent since they have no neighbours which fail to rhyme with them. Examples of such consistent irregular words are WALK, PALM, WEALTH, and LEARN. So there are four categories here, not three: there is a two-by-two classification, regular/irregular versus consistent/inconsistent, not a single continuum.

Experiment 1 of Glushko (1979) reported that reading-aloud reaction times (RTs) were 29 ms slower for inconsistent nonwords such as HEAF than for consistent nonwords such as HEAN, and also that that reading-aloud RTs were 29 ms slower for irregular words such as DEAF than for regular words such as DEAN. Since the nonword effect might have arisen because of the presence of irregular words similar to the nonwords and this might have produced some priming effect, Experiment 2 used only the nonwords from Experiment 1: here incon...