![]()

CHAPTER 1

Obtaining the Best Ideas

Innovation is the central issue in economic prosperity.

Michael Porter

THE COST OF WASTED IDEAS

In any organization, every employee possesses a unique viewpoint. These viewpoints create a tremendous opportunity. Under Toyota’s production system, which is seen as world class, not utilizing these employee ideas is actually seen as a form of waste (Ohno, 1988). This waste is placed in the same category as using more raw materials than are required, or the inefficiency of having to repeat a process due to a poor quality outcome. Thinking of failure to act on employee ideas as a form of waste helps to define the opportunity for more effective portfolio management.

Employees have many ideas for improvement of the work that impacts them. Some of these may be raised in the form of questions to the manager. Why do we do it this way? Some may occur over lunch, in hallway conversations, or while the employee is performing routine tasks. Many of these improvements can be made by employees on their own without the need for additional resources. Some of these ideas might entail 20 minutes of work to implement; some might require a 20-year effort. Some ideas might not merit any action when compared with other business options that meet the same need.

Although there is clearly no shortage of ideas within an organization, unfortunately, these ideas are seldom captured in most organizations, except in the few cases where a handful of employees are sufficiently entrepreneurial to drive their own ideas through to implementation. This can happen in spite of the organization, rather than because of it. Organizations are effective at focusing employees on their daily tasks, roles, and responsibilities. Organizations are far less effective at capturing the other output of that process: the ideas and observations that result from it. It is important to remember that these ideas can be more valuable than an employee’s routine work. Putting in an effective process for capturing ideas provides an opportunity for organizations to leverage a resource they already have, already pay for, but fail to capture the full benefit of—namely, employee creativity.

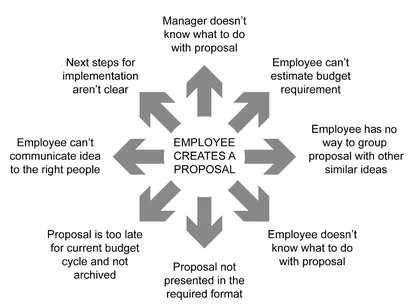

To assume that the best ideas will somehow rise to the top, without formal means to capture them in the first place, is too optimistic. Figure 1.1 identifies the risks of such a process. This Darwinian view of the process, or of organizations, may work for a subset of ideas, but many of the ideas lost along the way have significant merit and do not get implemented for other reasons, primarily because the junior employee has no easy way to communicate an idea to the broader organization. Also, to borrow another idea from the natural sciences, rejected project ideas may be useful in the future as the starting point for new and innovative project ideas. If they are not captured, this cross-pollinating between different ideas cannot occur. Organizations must drive innovation to remain competitive, yet they often fail to take advantage of the resources they have to make that happen.

Historically, capturing, ranking, and processing these ideas in a simple way across a broad network of employees would have been a major undertaking. But today with simple, portal-based solutions combined with portfolio management tools, setting up a process for doing this is low-effort and low-cost. Yet, the results are dramatic.

FIGURE 1.1 Risks of Informal Idea Capture Processes

PROJECTS AND INNOVATION

Innovation is a high priority for most organizations looking to differentiate themselves from the competition. For many organizations, sustainable organic growth is the strategic Holy Grail. Yet organizations frequently achieve far greater success with incremental improvements than innovations and consistently lament their ability to innovate. This should not be a surprise because genuine innovation is much harder to deliver consistently than incremental improvements. For example, in the field of electricity, it is easier to improve the efficiency of a steam turbine incrementally than to develop radically new, less-carbon-intensive energy sources. It is easier to make a better scalpel than it is to develop keyhole surgery. Generally, innovation requires forecasting or shaping of future trends, which is notoriously difficult, often because a combination of different trends must come together to make the idea viable. It also requires changes in organizational alignment that differ from the current organizational structure. Today’s product may be contained in a single division of the organization; tomorrow’s product may require multiple divisions to work together on different aspects of an innovation, while at the same time working on something that potentially threatens in-market products.

Innovation requires taking significant risk, fostering a creative mind-set, and collaborating across organizational boundaries. None of which is simple to do. In combination, these challenges appear daunting. Indeed, true innovation is likely to be proceeded by many apparent failures (Farson, 1970). Conventional project management systems must share some of the blame for the lack of innovation. Application of consistent metrics across all projects may hamper innovative activity. Innovations will fail far more often than typical improvement projects. Indeed, for innovations, a 10 percent success rate is good and 20 percent is spectacular. Success rates of 20 percent or less would be viewed as a disaster for any project portfolio targeted at incremental improvement. To drive real innovation, more ideas must be captured, ideas must be allowed to feed off each other to create more ideas, and metrics for success must be relatively soft during the early stage of the process.

WHY A LONG LIST OF PROPOSALS IS NECESSARY

Many organizations I speak with have a list of projects only about as long as they can execute. This makes it almost impossible for that portfolio to be strategic. “The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do” (Porter, 2008). If your list of projects is about as long as you can execute, then clearly there is not much you’re not doing. Of course, those organizations with a meager list of proposals might argue that there are many ideas that do not become proposals because they run into one impediment or another along the way. That may be true, but that sort of informal process is far from robust portfolio selection. Impediments are quite different from well-thought-out decisions. Putting in place a simple but consistent mechanism for idea capture can help dramatically increase the number of ideas that could become projects within the portfolio and magnify the portfolio’s effectiveness.

Regardless of the differing levels of rigor applied to projects, if there are only a handful of formal proposals, then any idea that is given serious consideration by management is implemented. There may be some modifications to the proposal based on feedback but, nonetheless, most submitted proposals will be implemented. Sometimes, the idea list might be only slightly longer than can be executed, but this deficit might only be realized several months into portfolio execution. This is costly because even though some level of selection is occurring, there is a clear cost of starting projects only to quickly replace them when a better idea comes along.

THE RISK OF INFORMAL PROCESSES

Informal processes risk generating inconsistent outcomes. Sometimes proposals are written up and analyzed in excessive detail. Yet, in other situations, only a cursory analysis is done before committing a major investment of resources. It is also frustrating to those submitting the proposals if there is no transparency or consistent rationale as to why their projects are not selected. Without feedback, it is hard for participants to improve their proposals or even remain engaged in the process. Another problem is that sometimes the level of influence of the project champion can be more important than the quality of the project proposal itself.

A simple, transparent process is important because, in order to collect a large number of strong proposals, idea submission must be encouraged by building faith in the proposal system. Without it, there will be a reluctance to submit proposals in the first place. Greater formalization of the process can also be encouraged by including an element of employee compensation. There is an opportunity to tie employee compensation to successful proposals, whether through patent filings or a portion of the cost savings generated. Such compensation will encourage submission.

Without grouping proposals together and analyzing them, it is a leap of faith to believe that the organization has naturally developed a process to get the best ideas onto the table without anyone consciously taking any explicit action or making any decision at the aggregate level. The ad hoc process is likely to be inefficient and more time consuming than a more structured portfolio selection process. Portfolio selection offers the opportunity to analyze proposals en masse, which can make it easier to calibrate across the group and can create efficiencies through economies of scale.

To take an extreme example, batch prioritization might require one meeting for 100 projects, as opposed to 100 ad hoc meetings if each project were considered individually. Therefore, it is key not just to have more ideas but to group those ideas together to ensure meaningful prioritization that is efficient from a time-management perspective. The grouping together of ideas is also helpful because it provides the opportunity to group similar proposals together into larger, richer proposals, and for the combination of proposals to spur new thinking and proposals. If proposals are considered in smaller sets—or worse, on an ad hoc basis as each proposal comes in—much of this cross-fertilization may not occur and an opportunity for further innovation is lost.

Another level of rigor can be applied to particularly risky or critically important projects. Here, proposals can be held in reserve to be executed, should the primary project fail or go irretrievably off course—as will likely occur across a large portfolio. For example, new problems may arise that need addressing, or compelling new ideas may arise based on customer feedback or market and competitive analysis. Although these ideas are healthy and often superior to project proposals being executed, this can disrupt the process, since the attempt to configure the portfolio on the fly is unlikely to lead to an optimal outcome. Resources on a canceled project will have been wasted, and recalibrating the project portfolio too frequently as new ideas come up may not be an effective use of time and resources. Managing this balance is critical; altering the portfolio creates adjustment costs, but reacting to changing market conditions rapidly and effectively can differentiate an organization from its competition.

It is rare that organizations are able to develop a broad and extensive list of projects to truly prioritize explicitly. Nonetheless, it is a complete list that enables strategic alignment in project selection. Without an extensive list of options, how can you arrive at the best permutation? As Napoleon said, “To govern is to choose.” But how can you choose without options? The best ideas do not come from you. The best ideas emerge from within your organization, given the unique perspectives of the different divisions and functional roles. These ideas must then be consistently reviewed so that you can meaningfully rank them against each other. It is clear that any attempt to prioritize ideas must start with an effective mechanism for capturing a large number of potential project ideas. This must occur even before the formal project proposal stage.

LOWERING THE BAR FOR IDEA SUBMISSION

The main reason for a lack of good project ideas within most organizations is simply that it is hard for employees to know what to do with their ideas. Ideas are not asked for explicitly from a broad enough set of people, in a transparent enough fashion, and on a regular enough basis. Idea generation typically is something that is seen as being valuable, but until recently, the technology has not been available for broad and simple idea capture, and the significant implementation costs have made most organizations reluctant to explore the area. Executives are receptive to new project ideas and would like to hear more of them—especially within a streamlined, simple process—but often the process for submitting project ideas is too complex or, worse, not defined. If all ideas must be justified by a 20-page analytical report listing the expected financial benefits and strategic rationale, then the number of ideas submitted will be low and, indeed, very similar to the set of ideas management already sees.

Often, the person able to come up with the spark of a new idea may not have the skills to perform a full analysis to justify or flesh it out in rigorous fashion. However, others must do that analysis in order to ensure that the best ideas are executed, or at least reach the stage where that analysis can be done. Therefore, more important than having a process is making sure that the process is simple and available to all within the organization.

Case Study: Managing a New Product Portfolio

Scott is managing a portfolio of new product launches. The goal is to extend an existing international consumer products company into new geographies and markets. Scott is “aiming toward incrementality” and “trying to be very efficient with his spend.” As there are many existing competitors in the market, there are a lot of analogs to existing products that could be introduced, Scott says, “We could not invent for 5 years and still bring out new product.” However, Scott takes a “core-satellite” approach to the portfolio, first targeting higher-volume productsto lead well in new markets and build relationships with partners, and then focusing on innovation, particularly in markets where innovation is expected by consumers such as Japan.

Scott’s process is fairly dynamic, built around monthly reviews with core stakeholders and quarterly reviews with all the international partner teams. In addition, the CEO will periodically contribute ideas into the pipeline based on market and competitive observations so the set of ideas under consideration is constantly expanding. It is easy to introduce a feasibility study for any product, but the amount of effort required to build the full business case, including financial estimates, can vary depending on how established the category is. As such, business cases are living documents. Testing is conducted to minimize risk. Concepts are tested online or via focus groups to generate more information that can feed into financial assessments. However, there is no mandated process for testing; the overall goal is to reduce financial risk through reducing uncertainty. “I don’t mind some uncertainty if the finance stakes are low,” he says. In cases where financial estimates are more uncertain, more testing will be performed; in areas where financial uncertainty is less, testing phases will be skipped to lower cost and increase speed to market.

Projects are ranked systematically across four core criteria:

1. Supply chain issues (cost, manufacturing feasibility, shelf life, etc.)

2. Market opportunity (customer demand, value proposition, incrementality)

3. Brand (degree of alignment with brand positioning)

4. Compete (competitive...