![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Laws of the Laws

Laws are like cobwebs, which may catch small flies, but let wasps and hornets break through.

—Jonathan Swift, “A Critical Essay upon the Faculties of the Mind,” 1709

The time is far in the future. A commercial space towing ship, the Nostromo,

makes an unscheduled stop at a remote planet, where one of the crew members is attacked by a parasite. A horrible scene in which the parasite bursts through his chest sets up the rest of the story in which each crew member meets a horrible death until only one remains. As it turns out, the encounter was intentional. The creature, a perfect killing machine, was known to authorities months before and they wanted to use the ship’s crew to bring one of them back so it could be weaponized. The crew, of course, had no idea.

—Synopsis of the movie

Alien

The lesson we can learn from Alien is profound and has many aspects. One lesson, perhaps, is that if you find yourself in an unknown situation, assume the worst case and don’t get too close to the unknown danger. Another is that if you don’t know your real mission, disaster is likely to follow. Alien is all about risk, the unknown single point of failure, and the consequences of operating in an undefined environment. The movie should be required watching in every organization and in every business school.

Have you ever considered the possibility that the premise on which you built your organization might not be valid anymore? It is a profound suggestion not only because the answer might startle you, but because the question does not occur to many of us. Poor Ripley, the sole survivor in Alien, thought she was towing ore and had no idea that she was really set up as bait for the perfect killing machine alien creature. And like the movie itself, the lessons have a lot to say about the nature of risk in today’s organization.

Risk is a parasite that resides in every process.

We have lost the association of risk as a threat or even as a negative. Risk itself has become meaningless. Terms like “risk management” and “risk expert” have normalized the concept of risk as a parasite and as a very real threat, not only to profitability and brand but often to an organization’s ability to survive. Much new risk has been introduced—threats once not relevant now impact global supply chains with greater frequency and consequences. Thanks to globalization, the risk parasite can quickly weave its way through the logistics, sourcing, and production processes that support these long tailed supply chains. The parasite can lie dormant in these processes, undetected by the organization. Then an event unleashes the parasite, creating a single point of failure, a broken link in the chain. The catastrophic outcomes can affect any stakeholder in the supply chain regardless of geographical or organizational boundaries. The trigger, large or small, can result in the same outcome. No longer can we distinguish between low probability /high impact events and everyday incidents. Whether an explosion at a natural gas plant or the availability of a single part, today’s interdependent and lean supply chains as well as a fiercely competitive global marketplace leave little space, or time, for error.

Consider, for example, that an explosion in western Australia in the summer of 2008 to an Apache Energy gas line significantly threatened global commodities supplies because Rio Tinto and Alcoa, two major miners in the region, lost power to their mines. Or, in another case, the shortage of components for windmills (which have 8,000 components) and solar panels has been hampering the growth of alternative energy. Even the failure of a single ingredient, such as osteoblast milk protein (melamine), in the food and dairy supply chain, can be far reaching. In a recent case, melamine was added to the product and allegedly killed eleven; sickened another 296,000; bankrupted Sanlu Group, a major Chinese dairy company; and caused significant negative global media attention to Fonterra Co-operative Group Ltd, a joint partner of Sanlu Group and a major contributor to the global dairy supply chain. The parasite was released; as a result, globally interconnected supply chains were idled. The release of the parasite is not limited to natural hazards or events that affect only physical assets. In June 2009, the Venezuelan government ordered Coca-Cola Company to withdraw its Coke Zero beverage from the country, citing unspecified health risks.1 No organization is exempt from the parasite and most have experienced its wrath—ExxonMobil Corporation, Fonterra Co-operative Group Limited, Rio Tinto Group, Gazprom, Cadbury Schweppes plc, Apache Energy, Wal-Mart, General Motors Corporation, Baxter, Intel, Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Microsoft, Toyota, and Mattel—to name only a few.

I think of the risk parasite as a metaphor to remind me how to address existing vulnerabilities and anticipate future challenges throughout the supply chain before they become catastrophic. The risk parasite knows no boundaries. It resides in every resource and attaches to every process flow. However, often an organization divides its supply chain risk defenses against the threat of a parasite by organizational functions. A security issue is treated by the Security Management group, an environmental issue by the Environmental, Health and Safety group, and an IT risk issue by the IT Risk group. Each function has its own assessment techniques and standards for measurement, as well as its own turf. However, the risk parasite does not distinguish between functions and locations. When the parasite is attached to the process, it can take on any form and easily travel up- and downstream in the supply chain. Unlike each of these groups, this invasive parasite has freedom of movement.

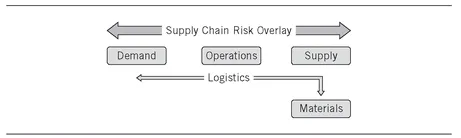

But risk management is not separate and distinct; the effective approach is to think of the supply chain risk management process as part of the supply chain network. It is an overlay to the major processes of the network: sourcing (material requisition, third-party management), logistics (transportation, distribution, warehousing, inventory management, IT/ERP), and production (manufacturing, assembly, subassembly). Refer to Exhibit I.1 in the Introduction. Simply stated, an effective supply chain risk strategy is one that is holistic and mirrors the supply chain network design and cash, information, and product flows, not just the functional design. The risk strategy is discussed further in later sections.

Exhibit 1.1 Supply Chain Risk Overlay

The strategic supply chain risk overlay shown in Exhibit 1.1 identifies and minimizes the impact of potential single points of failure, improves quality, protects critical data, and makes the supply chain more efficient. The risk parasite is a negative but realistic metaphor; the solution is to manage the whole body of the supply chain by identifying and removing, containing/isolating, or reducing the effects of the risk parasite.

Laws of the Laws

This book is organized into a series of laws that apply to everyone along the extended supply chain. However, before proceeding, I want to provide you with a brief set of questions about the nature of your business network, the value your organization creates, the supply chain relationship, and a definition of risk.

Questions to ask yourself before you proceed:

• How does my business create value and what role does the supply chain play in that process? Can I visualize the risk, worst-case scenarios, and impact at various points throughout the supply chain, as well as identify the point of maximum impact (i.e., maximum exposure)?

• How do my customers, investors, business partners, and other key stakeholders view and define supply chain risk, if at all? What are their expectations? How do they measure success and failure? Do they even consider these critical issues?

• What impact does my ability to manage supply chain risk have on protecting brand, ensuring margins, moving cash, and generating revenue to assure long-term growth?

• Who in my organization is responsible for the management of supply chain risk? Who at my third-party providers is responsible?

A good starting point for any challenge is to understand the context in which the solutions must be implemented. What are the practical realities of the culture, behaviors, and intangibles that cause the solution to succeed or fail? Most people know these unwritten rules, whether they are budgeting an expansion program, introducing a new product, eliminating manufacturing defects, or heading up a quality control team. This premise leads to four specific precepts that I call the Laws of the Laws. These specific points are articulated below and reflect how most of them successfully attack the parasite based on the unique culture of your organization. The ten laws of the supply chain risk process you find in the following chapters all have to address these four basic precepts on some level, and often on several levels.

Risk Management Defined

Before getting to these precepts, I have to start with the basic definition of risk management itself. There are many definitions in use and the meaning varies depending on your role. During my travels through Singapore, I ran into Rajeev Kadam, Vice President of Olam International Ltd., a global leader in the supply chain management of agricultural products and food ingredients. Rajeev articulated a simple but concise definition of risk.2

Risk has two essential components:

1. Uncertainty

2. Exposure to uncertainty

We face risk when both uncertainty and exposure are present.

Consider an example: A man jumps from a sixty-story sky-scraper. According to our definition above, there would be no uncertainty if the man were to jump off the building without a parachute. His chance of survival would be zero. However, if the man were to jump with a parachute, then there would be some degree of uncertainty about whether the man would live or die. The jumper faces risk because he is personally exposed to the uncertainty of the parachute failing to open. We could begin to calculate this uncertainty.

Suppose you are watching this event as a bystander from the pavement below this tall building. Are you facing any risk even if there is uncertainty in this event? The answer is no, because you are not personally exposed—unless the jumper is your relative, or has borrowed money from you, or you have a coffee shop on the pavement where he may crash land.

We could continue with this example but I am sure you understand the point. Uncertainty can be difficult to calculate, especially when the exposure is not understood or realized. This, by far, is the most fundamental challenge of supply chain risk management—organizations not knowing or understanding how exposed their supply chains are to uncertainty, or to how much.

You need to define exposure to uncertainty in terms of impact: the cost of the loss, and what that loss means in terms of stakeholders, your brand and reputation, and even to the basic ability to provide your goods and services to your customers. With this definition in hand, I can now introduce the practical realities, or the Laws of the Laws, to guide you with the execution of your own supply chain risk management. Consider these four precepts.

Law of the Laws #1: Everyone, without exception, is part of a supply chain.

Law of the Laws #2: No risk strategy is a substitute for bad decisions and a lack of risk consciousness.

Law of the Laws #3: It’s all in the details.

Law of the Laws #4: People always operate from self-interest.

The following will expand on these four precepts.

Law of the Laws #1: Everyone, without Exception, Is Part of a Supply Chain

It was a revolutionary innovation in assembly line automobile production when a major manufacturer decided to give any individual on the line the power to stop the process if he or she saw a flaw. Before that, without the vested interest, the theme “It’s not my job” allowed visible flaws to proceed through the line even though dozens of assembly line workers saw the flaws. Because “It’s not my job” was the cultural rule, several points prevented diligence on the assembly line:

• Pointing out quality and safety defects was seen as criticizing a fellow line worker.

• Delaying the process reduced shift output and was seen as a negative.

• Pay was based on units produced and not on quality.

All of these flaws added to supply chain problems rather than solving them. In the 1980s, Toyota Motors first employed jidoka, the concept of empowering workers to stop an assembly line to prevent defects. The goal was to make it possible for everyone, at all critical points, to understand their role in the greater goal of supply chain value creation and, when appropriate, participate. Th...