- 189 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The supply chain is a complex system of numerous, integrated stakeholders. These stakeholders are responsible for the transportation, storage, documentation, and handling of material goods and cargo. Each entity has its own unique relationship with and role within the chain as well as its own unique security requirements. The challenge of trying to

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

WHAT IS SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY?

1

WHAT IS A SUPPLY CHAIN?

For the purposes of this publication, we will need to define what it is that commonly comprises a supply chain and how all the links are interconnected through the lens of security. There are other versions for other applications, which can be similar. As we move ahead in our discussion of supply chain security, we need a benchmark, or at least a reference point, on what we mean by supply chain, including its components and relationships.

A supply chain is just that. It is a chain of interconnected links that facilitates the movement of supplies, or in other words, cargo, goods, material, products, etc. This chain can be very short with only a few links and handoffs, or it can be lengthy, far reaching, and complex, with dozens of links and handoffs. In the field of supply chain security, it is very important to have an understanding of the elements of a supply chain, both on academic and on practical levels. This is important, as in any serious endeavor. This way we can effectively understand what it is that is expected and what is the correct function or application of the link. We can then recognize what might be misaligned or askew and what can be done to correct the issue and protect it moving forward.

We will start at the beginning, otherwise termed as the origin. Then we will progress through the traditional links of the supply chain and then talk about how to best secure those portions. There is no one overall security panacea for the protection of the supply chain. To be truly effective, each link and handoff has to be examined, understood, and protected.

1.1 Origin

As mentioned previously, we need to understand what it is that we are looking at and have a common agreement as to its use, function, and how we can apply a security program. Be careful to know how participants using that portion of the chain define the term. Even the term origin has to be examined, and an agreement needs to be in place for you to fully appreciate what it is that will be required and what risks, even liability, exist within that link.

Origin generally means where the material is first introduced into the supply chain. Many security risks to material exist prior to being introduced into the chain. If you are responsible for the security of this portion, you will need to be sure if you are also responsible for the material prior to being added to your link. Very often, customers will indicate what they require or what you will need to provide by way of security for the material starting at origin. You must clearly research what the customer/client expects and how you might be held liable. We will talk more about this later, but you always should keep in mind the potential liability from both a security-program and a risk-management angle. A failure, theft, pilferage, or penetration will focus on a security breach, and someone will be liable for the monetary cost of the loss.

1.2 Manufacturing/Suppliers

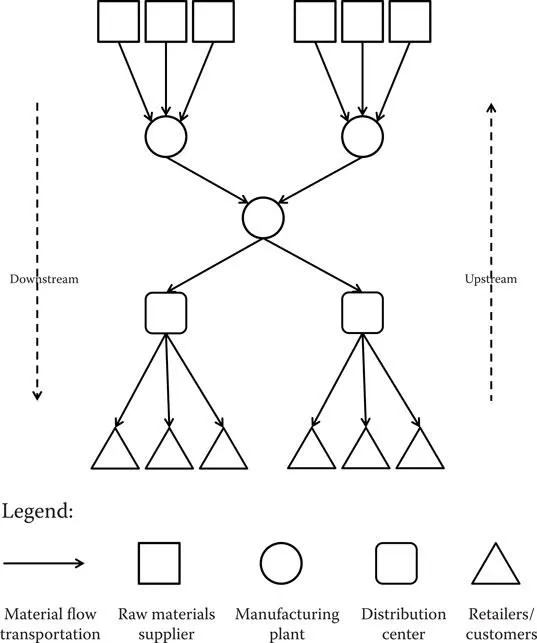

Many clients have or own their own plants, mills, etc., and ship to their own places of manufacture or assembly, or ship to their customers who utilize that material. Others procure material from other suppliers and then manufacture or distribute them for their own use or to others. You might be called upon to secure from that initial point of acquirement, or possibly from the time when they are ready to send out manufactured goods to distribution centers (DCs) or customers (see Figure 1.1).

In any event, this is usually the beginning of the supply chain. Goods are brought together, packaged for shipment, and then sent on their way through the chain to an expected end point. In some cases, logistics providers are hired to consolidate the materials from manufacturers/suppliers and to develop and apply appropriate packing for transportation and delivery.

1.3 Handoffs

This is usually the point of transfer to a service provider in the movement of the material. These transfers are known as handoffs. The client hands off or passes the material from their own possession, or from the possession of one of their agents or suppliers, to another for handling and possible transportation. Go back and look at Figure 1.1. A handoff occurs each time one function touches another.

This handoff is important, as there is also an exchange of paperwork that in most cases describes the material, manifests, packing slips, invoices, the current packing configurations, dimensions (DIMs—weight/height/length/width), condition of the material, and in some cases, values and government tax and tariff documents.

On the receiving end of the handoff is the custody portion of the transaction. Whoever is accepting this material is now in a custodial position until they complete their portion and hand it off to another.

1.4 Initial Service Provider

Along the chain there can be many providers of a variety of modes, but initially the first providers are generally ground transports from the site of manufacture to another destination for use by the client. These ground transportation providers can move from distances of short city streets to full cross-country long hauls.

1.5 Service Providers

As described previously, the first provider is usually ground transportation, or trucking. In some bulk instances, material is handed off directly to a rail provider using a rail siding or spur on the client’s property.

1.6 Trucking

Trucking operations are used in all corners of the globe, and all have similar uses and issues as well as similar security concerns. For the purposes of this discussion about understanding the security of the supply chain, we will look at two major methods of trucking: line haul and hub and spoke (see Figure 1.2).

Hub and spoke is just as it sounds. Trucks bring material into a center point or hub, and then transfer cargo to other trucks going to other destinations, like spokes in a wheel. The hub and spoke is a distribution type of network. Trucks that pick up material at a variety of locations in their assigned territories then bring these materials to a central facility that services a number of spokes or territories. These trucks are considered LTLs (less than full trailer loads). This means that the trailer is not loaded with the intent to deliver to only one destination. Some trucking facilities might fill a trailer at only one stop, but the intent is to bring all that material to a hub where it can be broken down, or redistributed, to other destinations. This creates efficiency for the trucking firms instead of having a truck drive to multiple destinations that can be at long distances or using complicated and time- and resource-consuming routes. Hub-and-spoke operations are points of handoff and pose a concern for the security professional. The material is off-loaded, separated by destination, and moved to other parts of the operation, to be placed with other materials from other sources and then set upon other trucks for other destinations.

Once the material is sorted, it is loaded onto a truck destined for another region where the client wishes the material to be delivered or passed to another mode, or type, of provider. In some instances, the spoke destination is another hub in a far-reaching location. This usually occurs when that hub services a nearby region or another service provider. At the same time, any accompanying paperwork must follow the material to comply with the client’s business and government transportation regulations. Each pickup, spoke, hub, handoff, and destination is a security threat and needs to be examined.

Line-haul (sometimes referred to as long haul) moves are different in that they take a load usually of one type of material or material from one client in an FTL (full trailer load) capacity to a single destination in another region, state, or even another country. This destination could be a distribution center or a direct delivery to a customer or a provider.

The handoffs for a line haul are limited. Usually it is done once at the origin location, then once at the destination. When finished, that particular trucking provider is released. There is no re-sorting, handling, etc., of concern to the provider.

1.7 Ocean Shipping

Providers who transport material via the high seas are the ocean providers. Container ships of many types embark and disembark material of all types using shipping lanes that crisscross the oceans between the continents. The speed of the ships can be, on average, 25 knots, or approximately 28 mph, over water. Depending upon the size, load, capacity, and weather, a shipment, moving from a North Atlantic port to a port on the west shore of Latin America could take anywhere from seven to eleven weeks (see Figure 1.3).

The relationship of an ocean provider to the supply chain is as a service provider who has been handed material, via either trucking or rail, and then moves this material to another port to be handed off to another provider for ground transport via either rail or trucking. Many ports around the world have railheads on their properties that have ocean box containers already loaded onto their rail cars, which are off-loaded directly to ocean port staging areas. The converse is also true.

There are number of handoff procedures that take place for ocean shipping. They generally involve receiving a loaded ocean container that is then loaded and off-loaded as requested. Port authorities, both local and national, have regulations that impact ocean shipping. Some of these address security, but they do not cover everything that can place material at a security vulnerability or risk.

Many ocean ports have their own internal form of trucking. These allow for the movement of the ocean containers as needed for staging, inspection, etc. They also move containers in and out of off-port property-holding yards to help in reducing congestion within the confines of the shipyards. This is another security concern that we will look at later.

Once the loaded ship reaches the desired destination port for the client material, the box is handed off to another trucking provider. This provider could take it to an end point or another handoff to a distribution center. This could be done by line haul or moving within another hub-and-spoke network.

Ocean carriers are often chosen to transport material because they can haul great loads of raw material like oil or grain from source continents to consumer or manufacturing continents. Also, used as container shipping, goods can be shipped for far less cost than shipping by air. The ocean cargo delivery times are, of course, more spread out, but when these time frames are calculated, they fit easily into client delivery and production schedules.

1.8 Airlines

Airlines, as a supply chain link, handle great volumes of cargo and material. Of course, they are also passenger carriers (which you often see coded as PAX). There is an entire segment of this industry, known as all-cargo or freighters, that is dedicated only to cargo and material (see Figure 1.4).

Airlines are utilized for any number of reasons. The most common are speed and material condition. The first, speed, is important due to the ability to deliver material quickly over large distances. Client production or contractual obligations may dictate the material needs to arrive on a specified point in time when the material origin is far removed from the destination. The other is the criticality of maintaining the material’s condition, as in the case of pharmaceuticals, which can be sensitive to variations in time and temperature. The faster they are packaged and delivered, the less risk to their certifications or spoilage factors. It stands to reason that a load of fresh flowers needs to be received by the customer as fast as possible. Time in transit is critical for some materials coming from producers in Latin America that are being distributed to many global points.

The different types of air transportation—PAX or all cargo—handle cargo in a similar fashion. However, when developing a security plan for client cargo using an airline, it will be very important to know how they each handle the cargo and what differences exist. Many passenger airlines are dependent upon the revenues they gain from moving cargo along with passengers and baggage. The netted crates and/or aluminum containers you see being loaded and off-loaded at passenger terminals is cargo material (see Figures 1.5 and 1.6). Passenger flights provide a wide choice of scheduling selection, since they are based on passenger routes and schedules. All-cargo flights are scheduled only two or three times a week, since they only move cargo.

There is another offering by the all-cargo industry called charter flights, and these present several options for the use of charters by clients. Primarily, these involve the volume of cargo being moved by a client. So...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF FIGURES

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I WHAT IS SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY?

- PART II DEVELOPING A SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY PROGRAM

- PART III REGULATION AND RESOURCE

- PART IV CASE STUDIES

- PART V APPENDICES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Supply Chain Security by Arthur G. Arway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Opérations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.