![]()

1

Introduction

Energy is the single most important problem facing humanity today

–Richard Smalley (1996 Nobel laureate in Chemistry [SMA04])

Humankind currently uses 410 × 1018 joules of commercially traded energy per annum. This is equivalent to the energy content of over 90 000 billion litres of oil. We are addicted to energy, and as most of this comes from oil, gas and coal, it can be said that we are addicted to fossil fuels. There is a logical reason for the first addiction: without a large energy input, much of modern society would not be possible. We would have few lights, no cars, less warmth in winter and no division of labour. Our society would mirror any pre-industrial society, with the majority of us being subsistence farmers. Much of the world population no longer lives like this, and few would be willing to turn back the clock. Unfortunately our second addiction, that to fossil fuels, is proving to have severe consequences for both humankind and the planet’s flora and fauna. The problem is climate change (often termed global warming) caused by a build-up of carbon dioxide and other gases in the atmosphere. The majority of these pollutants emanate from our use of carbon-based fossil fuels. This book is about breaking the second addiction, without compromising the first.

As has been reported in the world’s media for over 10 years, there is clear evidence that we need to move away from fossil fuels. The last decade has been the warmest since records began: mean global temperature is up 0.6 °C since 1900; sea levels are rising by 1–2mmper annum; summer arctic sea ice has thinned by 40per cent since 1960 [ROT99, VIN99]; and the Thames barrier (which protects London from flooding) is now being raised on average six times a year, rather than the once every two years of the 1980s. In addition, carbon dioxide emissions are still rising and will rise faster as the developing world develops, suggesting climate change will accelerate as the century progresses. The added costs of flood defences and building damage caused by more extreme weather are likely to be extensive within the developed nations. The human costs of agricultural failures, water shortages and possibly political destabilization within the developing world could be much greater.

It has been estimated [ROY00] that the developed world needs to cut its emissions of carbon dioxide by 60 per cent if carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere are to remain below 550 parts per million (ppm) – beyond which point irreversible damage will have been done. Changing technologies and changing the way we live to achieve this is likely to cost developed nations around one per cent of their gross domestic product (GDP) per annum by 2050 [AEA03]. Economic growth will mean that GDP will probably have tripled by then, suggesting that this sum is affordable. In addition, much of this cost will be offset by reductions in costs associated with increased flooding etc. However, the pre-industrial atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide was approximately 280 ppm; it is now around 370 ppm (a level not witnessed for over a million years) and rising at more than half of one per cent per annum. As we are already starting to see the effects of climate change, the changes found at 550 ppm might well be considered unacceptable, implying greater cuts are necessary – possibly of the order of 90 per cent. This will require us to develop and deploy a whole new sustainable energy infrastructure.

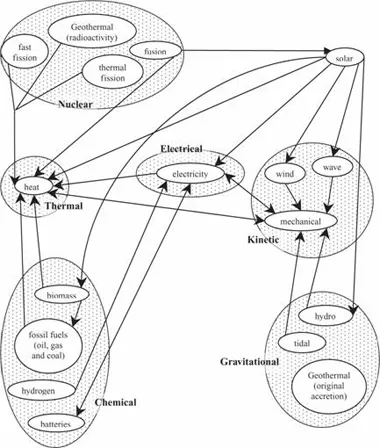

Figure 1.1 shows the major energy transformations, fuels and groupings studied in this book. It is clear that there are many sources of energy from which we can choose. In Parts II and IV we will define some of these as unsustainable and others as sustainable and examine technologies for their exploitation, but clearly there are many alternatives to fossil fuels.

The central question is: why haven’t we already made the switch to non-carbon fuels? There would seem to be two fundamental problems. Firstly, fossil fuels are cheap (crude has until recently traded at the same price as it did in 1880), and secondly, such fuels are highly energy dense. The first of these problems could in theory be solved by reducing income tax and other taxes, and taxing carbon instead. However, this might not find favour with voters, who are notoriously suspicious of new taxes, and it would also create difficulties for business unless the approach was adopted worldwide. Much more acceptable is probably the state subsidy of non-carbon alternatives and the pump priming of sustainable technologies to the point where they can compete with fossil fuels. In much of the developed world all three approaches are being applied to varying degrees and the cost of energy from alternative sources is falling rapidly. At the same time concern over climate change is growing. Together these signify a turning point both in the economic cost of renewables and the public’s concern about the future of the planet. This makes it an extremely exciting time to be involved in, or studying, energy and its impact upon the environment. No longer is the use of alternative energy a theoretical opportunity; it is an imperative. It is also happening all around us in the form of wind turbines, hybrid motor vehicles and the introduction of energy efficient technologies.

The second problem, the question of energy density, will be harder to solve. Filling a car’s petrol (gasoline) tank takes around one minute. This is a power transfer1 of 35 million watts (MW). (For comparison a typical domestic light bulb draws 100 watts.) To charge an electric car with this much energy would take around eight days through a domestic socket. It also means that a large filling station capable of simultaneously recharging 30 electric vehicles in one minute would draw 30 × 35 MW = 1050 MW, approximately the output of a nuclear power station. Other estimates lead to equally depressing conclusions. It would take a land area of around 940 000 km2 to grow energy crops capable of replacing all the UK’s fossil fuel use, close to four times the country’s total land area [CIA04a]. From this we can conclude that energy efficiency will have a major role in the energy policy of the future, but it is also likely that energy production will require larger land areas and be much more visible than it has been for many generations. It is worth noting that in 1900 the USA used one quarter of its arable land for the growing of energy crops for the transportation and work systems of the day – horses [SMI94, p91]. Today sustainable generation is likely to meet stiff resistance unless such technologies are conceived to fit within the landscape or are placed out of sight: for example roof-mounted solar panels or sub-surface tidal stream generators.

Possibly we will simply have to accept change. In the early nineteenth century there were around 10 000windmills operating in England [DEZ78]. An equivalent number of modern wind turbines each with a rated output of 2MWwould have a capacity equal to nearly 30 per cent of the UK’s power stations. We could therefore take this number as a historical minimum that the landscape is capable of holding without undue degradation. This would also return us to the idea of large-scale embedded generation where there is less geographic separation between generation and use. This could be described as the re-democratization of supply since we would all experience both the benefits and the consequences of energy supply.

It would appear that it will be far more cost effective to make reductions in carbon emissions early [AEA03, p44], even though the costs of sustainable technologies are probably at their greatest due to their infancy and low production volumes. The main reason for this is that if we delay our reductions, then to have achieved the same total carbon emissions over any fixed period we will have to make much larger cuts. This point is worth emphasising. It is the total cumulative amount of carbon (and other greenhouse gases) emitted that is key. Therefore the later we leave it the greater the required reductions will need to be, and beyond a certain date we will face the reality of either making cuts of over 100 per cent, which is clearly impossible2, or face a great degree of warming.

Unfortunately, environmental concerns often clash not just with our desire to minimize cost in the short term, but also with each other. The use of diesel as a fuel is common in buses and other public transport systems and it is used in great quantities within cities, creating a potential problem with local air quality. Its greater efficiency as a fuel though does mean its carbon dioxide emissions per km driven are typically lower. Its widespread adoption in private vehicles would therefore be beneficial in the fight against climate change, but would degrade local air quality. This is an example of an environmental dichotomy. We have a pair of options, neither of which is environmentally benign and, because they have differing environmental effects, it is very difficult to compare the relative magnitudes of the impacts. In this case the dichotomy is deepened because the impacts affect different groups. Changes in local air quality are largely ‘democratic’, in that those affected either own cars themselves, or derive wealth from the use of transport within the economy in which they live. However, the majority of greenhouse gas emissions are from more developed economies, whereas the majority of the future victims of climate change are likely to live in less developed economies. Climate change can therefore be seen as highly ‘undemocratic’. This reduces the pressure for change.

In the industrialized countries, around two thirds of carbon dioxide emissions are from the energy used for transport (mostly the private car), and heating and lighting homes. This implies that climate change and the need to switch energy systems is not a problem created by industry, but is the responsibility of all of us. No faceless commercial giant is accountable for these emissions, but you and I.

There is also the problem of resource depletion. We are accustomed to plentiful supplies of our most valued hydrocarbons, oil and gas. Yet given the rate of use, reserves of such fuels may only last a further 40 years, and as much of it lies in geopolitically unstable locations, there are concerns over the security of supply3. There are fortunately much greater reserves of coal, shale oil and tar sands, all capable of being converted to oil and gas, but at a price. We will not run out of carbon for a long time. It could indeed be argued that it is our overwhelming wealth in carbon that is the problem, in that it is creating a stop to innovation. Even those most sceptical about whether manmade climate change is upon us would probably agree that we simply can not afford the risk of releasing all this carbon to the atmosphere. Clearly there are challenges ahead. Is it not surprising that in the twenty first century we still make the majority of our electricity – our most valued fuel – by essentially setting fire to a pile of coal, or other fossil product, using the heat from this to boil water, then using the steam to blow a giant fan around?

Rather than other important local pollution issues, the energy-related problems we will be concentrating upon in this book are global in nature. In particular we are interested in climate change. If climate change is to be tackled seriously then the whole international community will need to be involved. To emphasize the global nature of the problem and the spirit of international co-operation required in finding a solution, this book has tried to present an international view of energy and its use. Where possible, resource estimates and historic trends are given for the whole world; detailed, national figures then being used to illustrate various specifics. We also present example applications of technologies from around the world, and ask the reader to solve problems centred on a variety of countries.

The text is organized into four parts. Part I asks the question: what is energy? We then discuss the size of natural energy flows such as winds and tides that might become sources of sustainable energy and introduce the central environmental concerns that arise from how we currently provide our energy. Part II describes each of the current major energy technologies in turn, from coal to nuclear power. Part III returns to climate change to see what the future may hold for us and describes the work of the international community in trying to find agreement over carbon emissions. Part IV introduces the new sustainable energy technologies that will hopefully form the basis of future energy production, including solar, wind and wave power.

Throughout the book you will come across many problems within the text. It is strongly recommended that you try and complete each of these before moving on. They have been designed to encourage you to engage with the material and to practice accessing tables, manipulating important data and concepts and analysing the results of simple calculations. With the confidence such practice brings, it is hoped that you will try to rationalize and debunk some of the articles that are often published in newspapers and other media. Frequently, this can have amusing results, quite at odds with what the journalists were trying to say. The use of only approximate values for any data is encouraged. The idea is to show that back-of-the-envelope style calculations often allow one to answer important questions. If you don’t know the values for some of the data, just guess. The same goes for how to actually answer the questions; just start manipulating the data you do know and the answer may just drop out.

As an example of the approach required, imagine one of the questions asks you to estimate the number of individuals who die in China (population 1.3 billion [CIA04b]) each year. Note we are not asking whether you already know the answer to this question, but to work it out using approximate methods. So, if the population is 1.3 billion and we assume most people die when they are, say, 70 years old then the answer is 1 300 000 000/70 ≈ 19 million per annum. If we had assumed that average age at death was 60 or 80, the answer would have been 22 or 16 million, respectively. Either way it probably doesn’t matter in the context in which the question is likely to be asked: it’s a very large number of people. Some students find such questions relatively easy; others find it difficult to work approximately. It is the author’s opinion that such simple calculations have a pedagogical role, in that they reinforce the learning process by helping students remember concepts, data and results.

Answers are given in an appendix, but please try to attempt each one before looking the answers up, or moving on.

The student exercises at the end of each chapter are a mix of numerical and essay-based ones, and are designed to test whether students have understood qualitative and quantitative concepts. Those wishing for additional quantitative exercises should extract and adapt relevant in-text problems.

![]()

PART I

Energy: concepts, history and problems

“Shame on us if 100 or 200 years from now our grandchildren and great-grandchildren are living on a planet that has been irreparably damaged by global warming, and they ask, ‘How could those who came before us, who saw this coming, have let this happen?’ ”

–Joe Lieberman

In this first part we will ask the question, what is energy? Despite being a concept central to the teaching of science in schools and universities, the concept of energy will prove to be difficult to tie down with a single satisfactory definition. We will then move on to discuss some of the environmental problems caused by the way we currently meet our energy needs. Central to this will be an introduction to climate change (often termed global warming), but other topics such as air pollution, acid rain and sustainability will also be covered.

The possibility of meeting all our energy requirements from sustainable renewable sources has been a dream of many for a long time. By reviewing the natural energy inputs to which the planet is exposed, we will see that there is in theory no reason why this cannot be achieved.

Another question that needs to be asked is: how important is energy to the functioning of society? In the past energy use was much lower, and only by considering how the evolution of society is connected to the development of new sources of energy will we realize the importance of the link. By appreciating the connection between energy use, wealth and development, we can see why poorer nations will, and must be allowed to, substantially expand their demand for energy. This connection is also possibly why many of the world’s politicians have shied away from the issue of climate change. Without a change to the way we derive our energy, this expansion will have significant implications for the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Finally we will examine some of the physical limits to the efficiency with which we can supply energy (or work). This will lead to an analysis of how our most valued form of energy – electricity – is generated and distributed.

![]()

2

Energy

“Our planet… consists largely of lumps of fall-out from a star-sized hydrogen bomb… Within our bodies, no less than three million atoms rendered unstable in that event still erupt every minute, releasing a tiny fraction of the energy stored from that fierce fire of long ago.”

–James Lovelock, Gaia

Before embarking on our journey through current and future energy systems and the problems that their use might cause, we need to achieve a firm understanding of what energy is in all its guises, its units and any fundamental constraints that exist in transforming it from one form to another.

2.1 What is energy?

So, what is energy? If you have a background in physics or engineering this might seem rather a strange question to ask. Using terms such as potential energy and kinetic energy might almost seem second nature to you now, but pause for a moment and ask yourself the question, what actually is energy?

We know from common experience that a rotating wheel, a hot cup of tea, the current flowing through a wire or a crashing wave are all objects or systems di...