![]()

CHAPTER 1

ERYTHROCYTES

Charles W. Brockus, DVM, PhD

BASIC CONCEPTS OF ERYTHROCYTE FUNCTION, METABOLISM, PRODUCTION, AND BREAKDOWN

I. THE ERYTHRON

A. This widely dispersed mass of erythroid cells includes circulating erythrocytes and bone marrow precursor, progenitor, and stem cells.

B. Its function is oxygen transport, which is mediated by hemoglobin.

C. Hemoglobin is transported in erythrocytes whose membrane, shape, cytoskeleton, and metabolic processes ensure survival of the cell against the stresses of circulation and various injurious substances.

D. Hemoglobin consists of heme and globin, and each complete hemoglobin molecule is a tetramer.

1. Each heme moiety contains an iron atom in the 2+ valence state (Fe2+).

2. A globin chain of specific amino acid sequence is attached to each heme group.

3. The complete hemoglobin molecule is a tetramer, containing four heme units and four globin chains. The globin chains are identical pairs (dimers), designated as α-chains or δ-chains.

II. HEME SYNTHESIS

A. Heme synthesis is unidirectional and irreversible. It is controlled at the first step by the enzyme δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase, whose synthesis is controlled by negative feedback from heme concentration within the erythrocyte.

1. Lead inhibits most of the steps in heme synthesis to some degree. Lead also inhibits the delivery of iron to the site of ferrochelatase activity.

2. Chloramphenicol may inhibit heme synthesis.

B. Porphyrins and their precursors are the intermediates of heme biosynthesis.

1. Certain enzyme deficiencies in the synthetic pathway can lead to excessive accumulation of porphyrins and their precursors.

2. These excesses of porphyrins and their precursors are called porphyrias.

3. Porphyrias vary in the intermediate products that accumulate and in their clinical manifestations.

4. These excess porphyrins escape the erythrocyte and may be deposited in the tissues or excreted in the urine and other body fluids.

C. After formation of protoporphyrin, iron is inserted into the molecule by ferrochelatase, and heme is formed.

III. GLOBIN SYNTHESIS

A. Each hemoglobin molecule is comprised of four globin chains, each of which binds to a heme group.

1. The hemoglobin type depends on the type of globin chains, which are determined by amino acid sequences.

a. Embryonic, fetal, and adult hemoglobins are found in various animals.

b. The presence and number of each hemoglobin type vary with the species.

2. Heme and globin synthesis are balanced (increase in one results in an increase in the other).

B. Abnormalities in globin synthesis (i.e., hemoglobinopathies) have not been described in domestic animals.

IV. IRON METABOLISM

Body iron metabolism/content is based on an extremely efficient system of conservation and recycling that is regulated by the rate of duodenal absorption rather than excretion. Hepcidin is a recently identified 25 amino acid peptide (bioactive form) produced within the liver and transported within the blood by α-2-macroglobulin. It has been found to play a key role in mediation of iron metabolism. In short, increased hepcidin is accompanied by a decrease in iron availability, whereas decreased Hepcidin is associated with an increase in iron availability. Hepcidin is a component of the type II acute phase response induced by interleukin-6 and controls plasma iron concentration by inhibiting iron export by ferroportin from enterocytes and macrophages. Absorption is regulated by the amount of storage iron (large iron stores decrease absorption) and rate of erythropoiesis (accelerated erythropoiesis increases absorption). Less than 0.05% of the total body iron is acquired or lost each day.

A. Iron is transported in blood bound to the δ-globulin, transferrin.

1. Iron bound to transferrin is measured as serum iron (SI). This is an unreliable measure of total body iron stores.

a. Conditions with decreased SI

(1) Iron deficiency

(2) Acute and chronic inflammation or disease (including anemia of inflammatory disease)

(3) Hypoproteinemia

(4) Hypothyroidism

(5) Renal disease

b. Conditions with increased SI

(1) Hemolytic anemia

(2) Accidental lysis of erythrocytes during sampling (hemolysis)

(3) Glucocorticoid excess in the dog and horse. In contrast, SI is decreased in cattle with glucocorticoid excess.

(4) Iron overload, which may be an acquired (e.g., iron toxicity) or hereditary (e.g., hemochromatosis in Salers cattle) condition. Iron overload in some birds (e.g., mynahs and toucans) also may be hereditary.

(5) Nonregenerative anemia

c. SI can be expressed as a percentage of total iron-binding capacity (TIBC, see below) and reported as the percent saturation.

2. TIBC is an indirect measurement of the amount of iron that transferrin will bind. An immunologic method is available to quantitate transferrin, but is not used commonly.

a. Only one-third of transferrin binding sites usually are occupied by iron. This is expressed as percent saturation.

b. TIBC is increased in iron deficiency in most species except the dog.

3. Transferrin can bind more iron than is normally present. Therefore, the numeric difference between TIBC and SI is the amount of iron-binding capacity remaining on transferrin or the unbound iron-binding capacity (UIBC).

B. Hepcidin has been found to be the main regulator of iron homeostasis; it is produced in the liver and acts systemically in iron overloading (increased) or in response to anemia or hypoxia (decreased). Hephaestin (an intestinal ceruloplasmin analog) and ceruloplasmin (synthesized in the liver) are both copper-containing proteins involved in iron transport. Ceruloplasmin also is an acute phase inflammatory reactant. Ferroportin 1 and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) are necessary for transfer of iron from intestinal epithelium and macrophages to serum transferrin. Hepcidin induces the internalization and degradation of ferroportin, thereby inhibiting iron transport.

C. Iron is incorporated into hemoglobin during the last step of heme synthesis. Lack of intracellular iron causes an increase in erythrocyte protoporphyrin concentration.

D. Iron is stored in macrophages as ferritin and hemosiderin.

E. Ferritin is a water-soluble iron-protein complex.

1. Ferritin is the more labile storage form of iron.

2. Small amounts circulate that can be measured as serum ferritin, which is an indirect measurement of the storage iron pool. A species-specific immunoassay is required.

a. Serum ferritin concentration is decreased in iron deficiency.

b. Serum ferritin concentration is increased in the following:

(1) Hemolytic anemia

(2) Iron overload

(3) Acute and chronic inflammation

(4) Liver disease

(5) Some neoplastic disorders (e.g., lymphoma, malignant histiocytosis)

(6) Malnutrition (cattle)

F. Hemosiderin is a more stable, but less available, storage form of iron that is comprised of native and denatured ferritin and protein. It is not water-soluble and is stainable within tissues by Perl’s or Prussian blue techniques.

G. Abnormalities in serum iron are related to absorptive failures, nutritional deficiencies, iron loss via hemorrhage, and aberrant iron metabolism with diversion to macrophages at the expense of hematopoietic cells (which occurs in chronic disease processes and inflammation).

V. ERYTHROCYTE METABOLISM

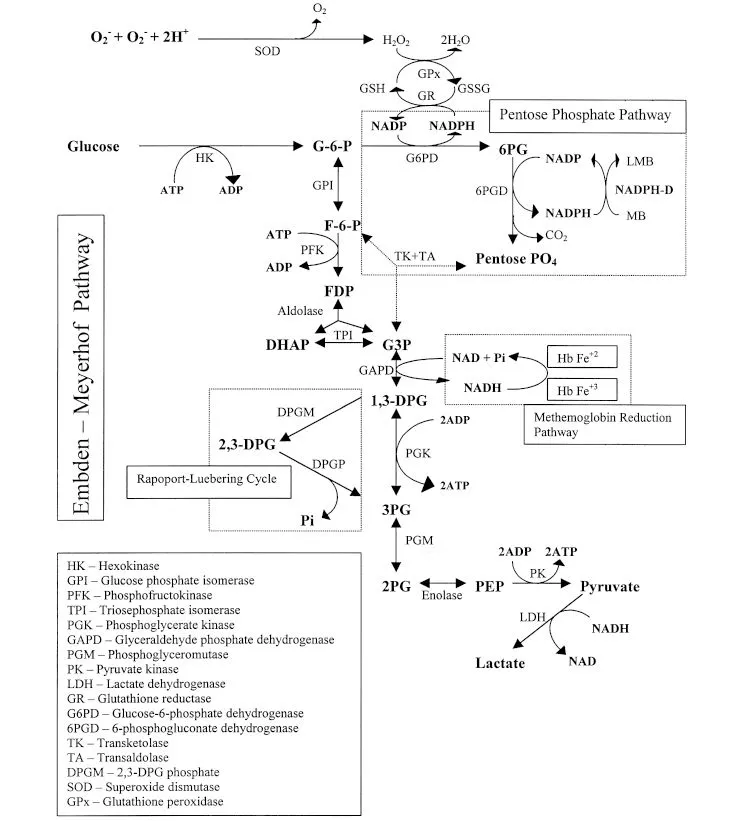

Metabolism is limited after the reticulocyte stage because mature erythrocytes lack mitochondria for oxidative metabolism. Biochemical pathways found in mature erythrocytes are listed in Figure 1.1 with their functions and associated abnormalities.

A. Embden-Meyerhof pathway

1. By this anaerobic pathway, glycolysis generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and NADH. ATP is essential for membrane function and integrity, whereas NADH is used to reduce methemoglobin.

2. Important enzymes in this pathway include pyruvate kinase (PK) and phosphofructokinase (PFK). Enzyme deficiencies in this pathway can lead to hemolytic anemia (e.g., PK and PFK deficiency anemias of dogs).

3. PK deficiency impairs ATP production, resulting in a macrocytic hypochromic anemia with 15% to 50% reticulocytes, myelofibrosis, hemochromatosis, decreased erythrocyte lifespan, and accumulation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and 2,3 diphosphoglyceric acid (DPG). PK deficiency has been reported in dogs (Basenji, West Highland White Terrier, Cairn Terrier, American Eskimo Dog, Miniature Poodle, Pug, Chihuahua, and Beagle) and cats (Abyssinian and Somali).

4. PFK deficiency results in decreased erythrocytic 2,3 DPG concentration, hematocrit (Hct) that is within the reference interval or decreased, persistent reticulocytosis, and alkalemia leading to hemolysis. This enzyme deficiency is reported in dogs (English Springer Spaniels, Cocker Spaniels, and some mixed-breed dogs).

B. Pentose phosphate pathway (Hexose-monophosphate pathway)

1. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is the rate-limiting enzyme in this anaerobic pathway.

2. This pathway produces NADPH, which is a major reducing agent in the erythrocyte. NADPH serves as a co-factor for the reduction of oxidized glutathione. Reduced glutathione neutralizes oxidants that can denature hemoglobin.

3. A deficiency or defect in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase results in hemolytic anemia under conditions of mild oxidative stress (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in the horse with eccentrocytes and Heinz bodies).

C. Methemoglobin reductase pathway

1. Hemoglobin is maintained in the reduced state (i.e., oxyhemoglobin; Fe2+) necessary for transport of oxygen by this pathway.

2. Enzyme deficiency results in methemoglobin accumulation. Methemoglobin (Fe3+) cannot transport oxygen, and cyanosis results. With substantially increased methemoglobin concentration, the blood and mucous membranes may appear brown.

3. NADH and NADPH methemoglobin reductases also are present. The former predominates in normal conditions and the latter is activated by redox dyes (e.g., methylene blue).

4. Methemoglobin reductase deficiency results in cyanosis, methemoglobinemia, pO2 within the reference interval, and exercise intolerance. This deficiency has been reported in dogs (American Eskimo Dog, Poodle, Cocker Spaniel-Poodle cross, Chihuahua, and Borzoi).

D. Rapoport-Luebering pathway

1. This pathway allows formation of 2,3 diphosphoglycerate (2,3 DPG), which has a regulatory role in oxygen transport. Increased 2,3 DPG favors oxygen release to tissues by lowering the oxygen affinity of hemoglobin.

2. Depending upon the species, some anemic animals usually have increased 2,3 DPG concentrations and deliver more oxygen to tissues with a lesser amount of hemoglobin (a compensatory mechanism).

3. Animal erythrocytes vary in the concentration of 2,3 DPG and its reactivity with hemoglobin. Dog, horse, and pig erythrocytes have high concentrations and reactivity, whereas cat and ruminant erythrocytes have low concentrations and reactivity.

VI. ERYTHROKINETICS

A. Stem cells, progenitor cells, and precursor cells (Figure 1.2)

1. Pluripotential and multipotential stem cells (CFU-GEMM or CD34+ cells)

a. These cells have the capacity for self-renewal and differentiate into progenitor cells.

b. Differentiation is controlled by growth-promoting stimuli produced by marrow stromal cells. A variety of growth factors and cytokines are involved (SCF, IL-3, IL-9, IL-11, and erythropoietin).

c. When a stem cell differentiates, it loses some of its ability to self-replicate and also loses some of its potentiality.

2. Progenitor cells

a. Some early progenitor cells have the capability of differentiating into more than one cell line (e.g., CFU-GEMM has the potential to differentiate into granulocytes, erythrocytes, monocytes, or megakaryocytes).

b. Other progenitor cells are unipotential (e.g., CFU-E can only differentiate into erythroid cells).

c. Progenitor cells have limited capacity for self renewal and differentiate into precursor cells of the various cell lines.

d. Progenitor cells are not recognizable morphologically with Romanowsky stains, but resemble small lymphocytes.

3. Precursor cells

a. Precursor cells have no capacity for self-renewal but proliferate while differentiating into the mature, functional cells.

b. These are the first cells that can be recognized as members of a particular cell line.

B. Erythropoiesis (Figure 1.3)

1. In mammals, erythropoiesis occurs extravascularly in bone marrow parenchyma. In avian species, erythropoiesis occurs within the vascular sinuses of the bone marrow (intravascular or intrasinusoidal development).

2. Characteristic morphologic changes take place during maturation from the rubriblast to the mature erythrocyte (Figure 1.4).

a. Cells become smaller.

b. Nuclei become smaller and their chromatin is more aggregated:

(1) Cell division stops in the late rubricyte stage when a critical intracellular concentration of hemoglobin is reached.

(2) The nucleus is extruded at the metarubricyte state, and a reticulocyte is formed in mammals. In contrast, avian reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes retain their nuclei.

c. Cytoplasmic color changes from blue to orange as hemoglobin is formed and RNA is lost.

3. In mammals, reticulocytes and erythrocytes migrate into the venous sinus of the bone marrow through transient apertures in endothelial cell cytoplasm.

a. Reticulocytes of most species remain in the bone marrow for two to three days before release and ultimately mature in the peripheral blood or spleen.

b. In health, the reticulocytes of cattle and horses mature in the bone marrow; mature erythrocytes are released.

4. The time from stimulation of the erythropoietic progenitor cell until reticulocytes are released is approximately five days.

5. Starting with the rubriblast, three to five divisions produce eight to 32 differentiated cells.

6. The bone marrow has the capacity to increase erythropoiesis.

a. Erythrocyte production can be increased up to seven times the normal rate in humans, providing the necessary stimulation and nutrients are present. This capacity to increase production varies with the animal species. It is greatest in birds and dogs and least in cattle and horses.

b. An inc...