![]()

Chapter 1

The Origins of Tea, Coffee and Cocoa as Beverages

Timothy J. Bond

Finlay Tea Solutions, Swire House, 59 Buckingham Gate, London SW1E 6AJ, UK

1.1 Introduction

What are the origins of tea, coffee and cocoa? How were they discovered and how did they become such important items in the everyday lives of billions of people? To answer these questions we need to cover a lot of ground from geography and social anthropology to plant biochemistry and human physiology. The so-called Western cultures began to consume these beverages only very late in their history, ‘discovering’ tea, coffee and cocoa through the forces of international commerce and trade and the expansion of their empires in the seventeenth century. Prior to that, the drinks had been consumed for a millennium, and as we shall see, the real ‘discoveries’ were that while many plants were toxic, tea, coffee and cocoa could yield products that could be consumed and have a beneficial impact on human physiology, emotional state and culture. Today, for many consumers it is difficult to imagine life without the first cup of coffee or tea of the day or without a chocolate bar.

1.2 The beverages in question

Tea, Camellia sinensis, is a small tree native to the Assam area of North India where North Burma and South China meet. This region has had a tumultuous history, linked to the Opium Wars between the United Kingdom and China, and the War of Independence between the United States and the United Kingdom, the growth of urban centres, the expansion of the British Empire, the birth of the British Industrial Revolution and many more events. After water, tea is now the most consumed beverage in the world (UK Tea Council 2010), drunk for both pleasure and health.

Coffee is produced from the seeds of another small tree, originating this time from Africa, spread via the slave trade to the Arabic empires where it gained pre-eminence due to the Muslim ban on fermented alcoholic beverages. Coffea arabica, Coffea robusta and Coffea liberica were discovered later and were transplanted across the world to establish plantations/estates in as far away places as Hawaii, Brazil and Vietnam. From this position, coffee has become, after oil, the second most valuable traded commodity on the global stock market.

Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) originates from the rainforests of Central America. As a drink, it was once the preserve of the Mayan and Aztec elite and a form of currency. It became intimately linked to Cortez's pursuit of gold in Southern America, and was much loved by the Spanish court. Cocoa made the move from drink to chocolate to become the favourite snack of the world's children and numerous ‘chocoholic’ adults.

These products created change not only in our societies and habits but also in our overall health and drove major changes in transport, especially shipping, contributing to the development of major ports such as Hamburg and Hong Kong, and indirectly creating markets for European pottery and silverware.

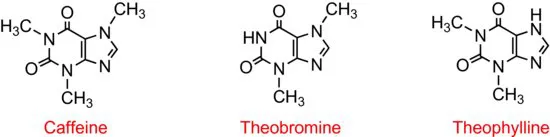

Chemically, cocoa, tea and coffee all comprise complex mixtures of plant secondary metabolites (see Chapters 2, 3, 5 and 7). Key amongst these are the purine alkaloids caffeine, theophylline and theobromine (Figure 1.1), which have an impact on alertness and are the basis of the ‘pick-up’ effects of all three beverages. In addition, simple and complex polyphenols are present, which provide taste and colour characteristics. The exact make-up of these constituents is influenced by the type of raw material, its origin, processing that is driven by manufacturing technology, and whole empires for the growth, trading, blend and distribution of these plant materials as they migrate from bush to cup.

The three beverages were unknown to Western civilisations prior to the seventeenth century. Today, they are items for everyday consumption, having been converted from very different cultural uses. Tea was originally a medicine, coffee was as a religious aid and symbol, and cocoa was the ultimate status symbol consumed by gods, priests and royalty. But where did they come from, who ‘discovered’ and introduced them to Western cultures and how did they assume their current paramount importance?

1.3 Discoveries – myth and legend

The discovery and initial utilisation of tea, coffee and cocoa as beverages are very much the stuff of myth and legend, and some of the earliest stories presented here should be treated as just that – fascinating and insightful, but with limited credibility. These mythical tales are chiefly a consequence of how the histories of the discovering cultures were recorded. In the case of tea, the character representing tea seems to have evolved along with language in general, so it is difficult to be sure that in the earliest texts, the ‘tea’ being referred to was not some other bitter herbal infusion. In Ethiopia, where coffee has its origins, history was mainly verbal rather than written, and in Mesoamerica, the pictographic language of the early civilisations has only recently been deciphered and even then is open to different interpretation. This makes verifying the information difficult but does give a flavour as to the origins of these beverages.

1.3.1 Tea

Tea is intimately linked with Asia, herbal medicine and Buddhism. Almost 4000 years ago, in 2737 BC, the great herbalist, ‘Divine Healer’ and Chinese emperor Shen Nung discovered tea (Ukers 1935). The story is that he observed leaves that had fallen from a nearby and unassuming tree (Plate 1.1) being boiled in water by his servant. Upon tasting the brew, the emperor found it to his liking and thus green tea was ‘discovered’. This also indicates that the Chinese already knew the value of making water drinkable by boiling it to kill microbial contamination. This habit still remains in China to this day where boiled drinking water is preferred, being served still and warm, rather than the glass of cold iced water demanded by other cultures. Tea, as luck would have it, has antimicrobial properties from the inherent catechin and caffeine contents, so it has a double benefit when consumed hot! In Chinese herbal medicine, ‘bitter’ is seen as a desirable trait; it would be interesting to see how the story might have evolved if tea had been discovered by a society that did not value this taste to the same extent.

This part of the story of the discovery of tea is well-established mythology. What is less well known is what became of the Shen Nung, father of tea. Shen Nung, tea and Chinese herbal medicine are all intimately linked. The emperor went around tasting innumerable herbs and plants, cataloguing them and documenting their health-promoting properties, and published his findings in the Pen ts’ao or Medicinal Book. It was during the course of this work that he reputably tasted a herb that was so poisonous that it could kill you before you had taken ten steps. Only tea leaves could save him, but alas none was available and he died after taking seven steps. How an author could publish a book having died during the course of his research is an interesting question, but not the only one surrounding the historical accuracy of Shen Nung's book. In the discovery of tea, much hinges on the following passage in the good book:

Bitter t'u is called cha, hsun and yu. It grows in winter in the valleys by the streams, and the hills of Ichow, in the province of Szechwan, and does not perish in severe winter. It is gathered on the third day of the third month, April, and dried. (Ukers 1935)

It seems that again we have some controversy as both Szechwan and Fujian provinces claim to be the historical home of tea. This aside, there is a historical linguistic issue with this quotation as the term ‘cha’ came into use only after the seventh century. The first Chinese book of tea the Ch'a Ching, published in 780 AD by Lu Yu, is widely recognised as an authoritative text covering harvesting, manufacturing and preparation of the beverage, as well as its consumption and history (Ukers 1935).

Despite the conjecture about the precise origins of tea, it is widely acknowledged that it was discovered in China and spread from there to surrounding countries and then onto Japan, sometime during the eighth century. Not to be outdone though, Japanese have their own myths about the birth of tea in China. The Japanese version of events is that Bodhidarma, a Buddhist saint, fell asleep during meditation. Furious with himself, a not very Buddhist sentiment, and to ensure that this did not happen again he cut off his eyelids and threw them to the ground. A bush sprang from the ground where they landed, with leaves curiously of the same shape as his eyelids, which when brewed produced a drink that banished fatigue (Ukers 1935).

1.3.2 Coffee

Coffee's discovery is just as emotive, of which we have hints in the naming conventions of the types of coffee that are now consumed around the world. Coffee is thought to be a native of the Kefa region of old, which was also known as Harar, in Northern Africa (Allen 2000). Decimating the ancient kingdoms, Western empires divided Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to artificially create territories of control. The Kefa region is now in Ethiopia. Legend has it that sometime around 850 AD in Abyssinia, current-day Northern Ethiopia, a goat herder named Kaldi noticed that his goats were acting in a rather strange way, with even the oldest of them running and gambolling in the heat of the midday sun. Paying attention to this, he noticed that they were especially frantic after eating red berries from a small, broad-leaved shrub (Roden 1981). These red berries were, of course, coffee cherries – the red, fleshy ‘berry’ covering the green coffee bean, the seed of the coffee tree (Plate 1.2). From here the legend diverts from Kaldi either to the abbot of a local monastery or, via trade, to the abbot of a monastery in Yemen. Either way, the resident abbot seems to have been concerned with a lack of alertness of monks during early morning prayers (Ukers 1922). Hearing of the effects the beans had on goats, he tried them on the acolytes, and again, we have a link between an invigorating beverage and keeping awake during religious ceremonies with, in due course, coffee trees becoming common fixtures of monastery gardens across the Arab world.

Coffee was not initially consumed as a beverage; instead, the beans were often mixed with fat and eaten as a high-energy snack during long journeys (Allen 2000). Between the first and fifth centuries AD, a lucrative trade route between Arabia and East Africa grew up, with slaves as one of the most valuable commodities (Segal 2002). Coffee seems to have been brought by the slave trains overland from Ethiopia and across to the port of Mocha, a name that still has meaning for the modern-day coffee connoisseur. It is said that coffee trees line the old trade routes as a result of discarded snacks along the way, germinating to produce the berry-yielding trees. The Mocha region, which is in current-day Yemen, became both a major area for cultivation and the ancient port from which coffee was exported to the rest of the world.

How coffee was converted from a food to a beverage is less clear, though there are accounts of a ‘fermented beverage’ being produced from the red coffee cherries (Ukers 1922). Like other food and beverage items, the modern-day incarnation of coffee is very different from its origins. In the case of modern coffee, the cherries are picked and the outer pulpy ‘cherry’ removed either by soaking in water (wet coffee) or alternatively the cherries are laid out to dry in the sun (dry coffee) and the dried outer coating is removed by abrasion. With both methods the removal of the covering reveals the green coffee beans that are the cotyledons of the seed. But this is not coffee as we know it; the beans must be roasted to a dark-brown/black colour, the effects of which develop the rich aroma and characteristic taste of the coffee. The roasted beans are ground to a coarse/fine powder and finally infused in boiling water to produce what we would consider a ‘cup of coffee’. What brought about the move from beans in a ball of fat to the ‘roast and ground’ coffee drink we recognise today is far from clear, but another tale of the discovery of coffee may throw some light on the matter. This time the tale is of:

… the dervish Hadji Omar was driven by his enemies out of Mocha into the desert, where they expected him to die of starvation. This undoubtedly would have occurred if he had not plucked up the courage to taste some strange berries which he found growing on a shrub. While they seemed to be edible, they were very bitter; and he tried to improve the taste by roasting them. He found, however, that they had become very hard, so he attempted to soften them with water. The berries seemed to remain as hard as before, but the liquid turned brown, and Omar drank it on the chance that it contained some of the nourishment from the berries. He was amazed at how it refreshed him, enlivened his sluggishness, and raised his drooping spirits. Later, when he returned to Mocha, his salvation was considered a miracle. The beverage to which it was due sprang into high favour, and Omar was made a saint. (Ukers 1922)

Coffee initially gained acceptance in the Muslim world as an acceptable, non-alcoholic drink that also conveniently removed fatigue before prayer.

1.3.3 Cacao products

Cacao is more sensitive to agronomic conditions than are tea and coffee, the tree being broad leafed and thriving in narrow climatic conditions defined by shaded areas in latitudes within 20 degrees of the equator (Coe and Coe 2003). Cacao is Theobroma cacao according to the Linnaeus classification system. Theobroma means ‘food of the gods’, which shows either Linnaeus great reverence for the product or his understanding of the cultural relevance of cacao. Cacao originates from the rainforests of Central America, sometimes termed ‘Mesoamerica’, wh...