eBook - ePub

Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food Sector

Implications for the Future

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food Sector

Implications for the Future

About this book

Providing an overview of nanotechnology in the context of agriculture and food science, this monograph covers topics such as nano-applications in teh agri-food sector, as well as the social and ethical implications.

Following a review of the basics, the book goes on to take an in-depth look at processing and engineering, encapsulation and delivery, packaging, crop protection and disease. It highlights the technical, regulatory, and safety aspects of nanotechnology in food science and agriculture, while also considering the environmental impact.

A valuable and accessible guide for professionals, novices, and students alike.

Following a review of the basics, the book goes on to take an in-depth look at processing and engineering, encapsulation and delivery, packaging, crop protection and disease. It highlights the technical, regulatory, and safety aspects of nanotechnology in food science and agriculture, while also considering the environmental impact.

A valuable and accessible guide for professionals, novices, and students alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food Sector by Lynn J. Frewer,Willem Norde,Arnout Fischer,Frans Kampers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: Fundamentals

1

Intermolecular Interactions

1.1 Introduction

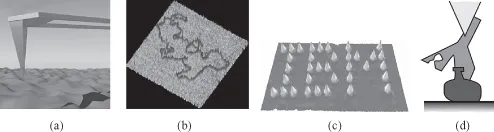

Nanotechnology may be broadly defined as the study, fabrication, and application of systems by manipulating structures or objects having nanoscale dimensions (say, between 1 nm and 100 nm). Of course, molecular scientists, in both chemistry and biology, have been dealing with nanoscopic (polymer) molecules and biological cell components for decades. So, what’s new? New is that, with the advent in the 1980s of new instrumentation, in particular scanning probe microscopes – for example, atomic force microscopy (AFM) – individual nano-objects can be observed and manipulated (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Atomic force microscopy. (a) The topography of a surface is scanned with subnanometer resolution, so that nano-sized objects can be (b) observed and (c) manipulated. (d) Atomic force microscopy may also be applied to determine the interaction between two objects.

Using AFM, the positions of molecules and nanoparticles, relative to each other, may be rearranged in a controlled way. AFM furthermore allows the measurement of interaction forces between nanoparticles as well as between nanoparticles and macroscopic objects. Other recently developed devices, the so-called optical tweezers and magnetic tweezers, also enable the controlled motion of, and the determination of forces between, nanoparticles.

Manipulation on the nanoscale may be done in two “directions”, referred to as top-down and bottom-up. In the top-down approach, structures are made increasingly smaller by progressively removing matter, usually by etching. Perhaps the most well-known example of a top-down structure is the electronic chips present in various devices. Another example is the micro- or nano-sieve, a solid wafer punctured with equally sized micro- or nanopores. Nano-sieves are in particular relevant for food processing and water treatment. Because various agricultural and dairy products are of heterodisperse particulate nature, that is, emulsions, foams, and dispersions of solid particles, they may be fractionated using a series of sieves of varying pore size. The separate components thus obtained may be recombined to give newly composed products of superior quality. Also, nano-sieves could be used in (cold) sterilization by filtering out microbial cells.

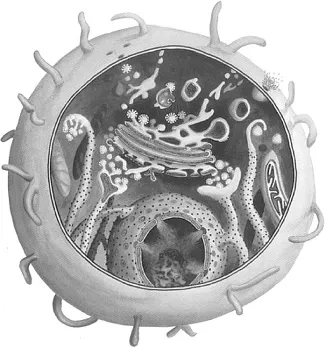

In the agri-food sector, however, bottom-up nanostructures are more often encountered. Bottom-up implies that atoms or molecules are distributed and rearranged to build new, functional nano-objects. Nature itself is full of bottom-up nanostructures, especially in living species. Think of viruses, where nucleic acids and proteins are arranged and interact such that viral activity results. Think of microbial, plant, and animal cells in which the various nano-sized organelles and membranes are complex bottom-up assemblies of precisely arranged building blocks (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Cartoon of a biological cell showing a variety of nano-sized subcellular structures.

Although nature is capable of making structures far more complicated and sophisticated than the ones that scientists can – for the time being – achieve in their laboratories, it may not be a surprise that nano-engineers are strongly inspired by nature. A few examples come to mind: in making addressable biocompatible nanoparticles to be used for the encapsulation and delivery of nutriceuticals and pharmaceuticals, nature provides clues as to how the surface of such particles should look; viruses may serve as a model in the design of particles carrying deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragments to be used in gene therapy; non-fouling surfaces may be mimicked from the outer composition and structure of cell surfaces; and the texture of foodstuff may be optimized by imitating nanostructures as they occur in nature, for example, fibrillar protein aggregates in meat replacers and three-dimensional polymer networks in mousses.

To achieve the specific architectures related to the desired (biological) function of the nanostructure, the physicochemical interactions between the building blocks should be tuned with high accuracy. Needless to say, understanding the mechanisms underlying the various types of interaction is a prerequisite for successful tuning.

In this chapter an introduction to the main types of interactions that may play a role in bottom-up nanotechnology is given. These are physicochemical interactions more or less sensitive to changing environmental conditions and therefore result in the formation of annealed, responsive structures. The discussion here may not be the most rigorous one, as, in view of the scope of this book, the scientific language of chemistry and physics that involves formulas and equations will be avoided as much as possible.

In natural systems, including those of the agri-food sector, most nano-objects exist by virtue of their interaction with an aqueous environment. Not only their existence but also their shape and spatial structure are to a large extent determined by their interaction with water. It is, therefore, essential first to pay attention to some physicochemical properties of water.

1.2 Water

Water is one of the most abundantly occurring chemical compounds on Earth (although very unevenly distributed). Because of its ubiquity, we are inclined to think of water as a trivial, common, and normal liquid. However, from a physicochemical point of view, water is a highly extraordinary substance. By virtue of its unique properties, water is the medium in which life has evolved and is sustained. Which properties make water so special, and how can these properties be explained and understood at the molecular level?

Water, H2O, has a molar mass of 18 g mol−1. Under ambient conditions, water boils at 100 °C. Among other components of comparable molar mass, this is an exceptionally high temperature. For instance, the boiling points of methane (14 g mol−1) and ethane (30 g mol−1) are −162 °C and −88 °C, respectively. Also, the heat of vaporization, which is essentially the energy required to separate the molecules when they go from the condensed liquid phase to the gas phase, is extremely high for water, 2255 J g−1, whereas for methane and ethane this is a little more than 500 J g−1. Another interesting property is the heat capacity, the amount of heat needed to increase the temperature of a substance by one degree Celsius. For the sake of fairness, equal amounts of the substances should be compared and at the same temperature and pressure. While the heat capacity of water at 20 °C and 1 atm amounts to 4.18 J K−1 g−1, the values for other liquids are much lower (cf. for chloroform it is 0.90 J K−1 g−1 and for ethanol 2.49 J K−1 g−1). These anomalously high values for the boiling point, heat of vaporization, and heat capacity (and, in this context, further extraordinary characteristics of water could be presented) originate from the phenomenon that water molecules attract each other. They attract each other so much that they strongly attach to one another. In scientific terms, water shows a strong internal coherence. Hence, to evaporate the liquid, favorable interactions between the water molecules have to be disrupted (which explains the large heat of vaporization), and this does not occur before the molecules have attained strong thermal motion (explaining the high boiling point). The large heat capacity reflects not only that heat is used for increasing thermal motion (corresponding to a one degree temperature rise) per se, but also that loosening of the internal coherence is necessary to increase thermal motion, which is the major energetic cost.

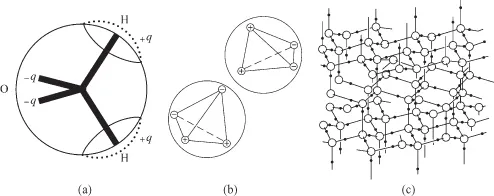

To understand the strong internal coherence, we zoom in on the molecular structure of water. Figure 1.3a shows a model of the molecular architecture of an H2O molecule. The hydrogen (H) atoms are very small relative to the oxygen (O) atom. Hence, the H2O molecule is nearly spherical, having a radius of about 0.14 nm. Atoms consist of a positively charged nucleus around which negatively charged electrons are orbiting. Hydrogen atoms have the tendency to donate their electrons for sharing with oxygen, which eagerly accepts that donation. Hydrogen is an electron donor and oxygen is an electron acceptor. Because of the positions of the H atoms relative to the O atom, the charge in the (overall electrically neutral) H2O molecule is not evenly distributed. Positive charges (+q) are centered on each H atom, and compensating negative charges (–q) are on the opposite sides of the O atom.

Figure 1.3 Water. (a) Model of a water, H2O, molecule showing the positive charges +q on the hydrogen atoms and the negative charges –q on the oxygen atom. (b) Polar interaction occurs through so-called hydrogen bonds between water molecules. (c) The three-dimensional structure of a water lattice in which all potential hydrogen bonds are realized (i.e., ice).

Because of those positive and negative sides, H2O is said to be a polar molecule. It is the polar character of the molecules that causes the strong internal coherence in water: the positive and negative poles attract each other (Figure 1.3b), so that each H2O molecule tends to be connected to four other H2O molecules via so-called hydrogen bonds. In its solid state, ice, the water molecules are in more or less fixed positions, with all four hydrogen bonds realized. Owing to the positions of the poles on the H2O molecules this results in a relatively open structure (Figure 1.3c) with an H2O volume density of 55%. When put under pressure some hydrogen bonds may become disrupted and the regular ice structure will be distorted: ice melts under pressure, and in the liquid state H2O has a somewhat less open structure or, in other words, a higher density than in the solid state. This is another peculiarity of water. In the liquid state the H2O molecules are still strongly associated in clusters and participate in about three out of the potential four bonds per molecule. Contrary to what one would expect for an associated liquid, the viscosity, that is, the fluidity, of water is not strikingly different from that of other, non-polar, liquids. The mobility of the individual water molecules in the clusters, underlying the macroscopic fluidity of the liquid, is retained, because the molecules readily rotate and hop about every 10−11 s from one partner to another, while having most, but not all (as in ice), hydrogen bonding potentialities satisfied.

Another property of water that deserves attention is the dielectric constant. Without going into detail, the dielectric constant is a measure of the ability to screen the electrostatic interaction between two charges at a given separation distance. Water has a high dielectric constant: in water, electrostatic interaction is 20 times weaker than in chloroform and about five times weaker than in ethanol. It is for this reason that salts in water dissociate into their oppositely charged ions. For the same reason, (bio)polymers, such as proteins, DNA, and polysaccharides, as well as synthetic polymers that contain ionizable groups, acquire charge in an aqueous medium. And so do the surfaces of (solid) materials when they are exposed to water.

Now, having gained some insight into some relevant characteristics of water, we may be able to understand the crucial role of water in shaping bottom-up nanostructures.

1.3 Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Interactions

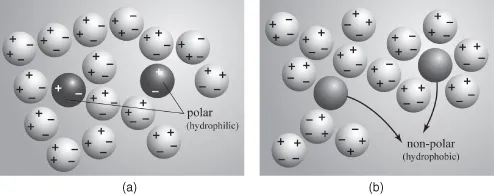

It has been illustrated and discussed in Section 1.2 that water is a strongly associated liquid because of favorable polar intermolecular interactions. Addition of another substance (referred to as “solute”) will disturb the coherence between the water molecules (Figure 1.4). If the solute molecules are also polar or have a net charge (ions), the polar water molecules interact favorably with the solute as well, just as they do with other water molecules. In that case the solute readily dissolves in water. The polar substance is called hydrophilic. Salts, sugar, and alcohol are examples of hydrophilic substances. However, if the solute is uncharged and non-polar (i.e., does not have an uneven charge distribution over its molecule), the water molecules prefer to stay attached to each other rather than to the non-polar solute molecules. This results in the non-polar molecules being expelled from the water and driven together to form a separate phase. Oils and fats therefore do not mix with water. For the same reason, the surfaces of plastics, Teflon, and so on, are poorly wetted by water. Such substances, disliked by water, are referred to as hydrophobic.

Figure 1.4 (a) Polar and (b) non-polar molecules immersed in water.

The description given above of water bordering other substances is highly simplified, especially in the case of non-polar, hydrophobic materials. There are still controversial issues to be solved. Nevertheless, theoretical and experimental studies indicate that, at hydrophobic surfaces, reorientation of water molecules imposes a higher degree of structural order in the adjacent water layer (the so-called hydration layer). Obviously, water molecules bordering non-polar surfaces tend to arrange themselves in a preferred orientation that allows them to form as many H bonds as possible with water molecules in the nearest-neighboring ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Part One: Fundamentals

- Part Two: Basic Applications

- Part Three: Food Applications

- Part Four: Nanotechnology and Society

- Index