- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book will address the-state-of-the-art in integrated Bio-Microsystems that integrate microelectronics with fluidics, photonics, and mechanics. New exciting opportunities in emerging applications that will take system performance beyond offered by traditional CMOS based circuits are discussed in detail. The book is a must for anyone serious about microelectronics integration possibilities for future technologies.

The book is written by top notch international experts in industry and academia. The intended audience is practicing engineers with electronics background that want to learn about integrated microsystems. The book will be also used as a recommended reading and supplementary material in graduate course curriculum.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access CMOS Biomicrosystems by Krzysztof Iniewski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Microelectronics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I: HUMAN BODY MONITORING

1

INTERFACING BIOLOGY AND CIRCUITS: QUANTIFICATION AND PERFORMANCE METRICS

1.1 INTRODUCTION

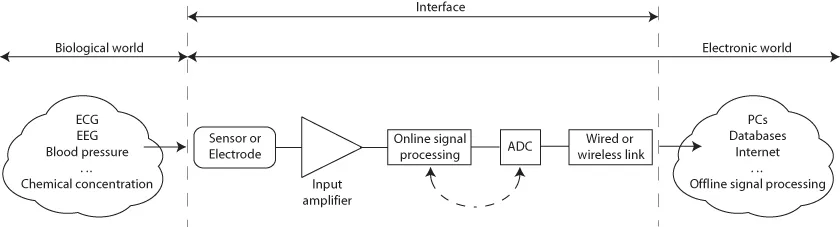

A key aim of bioelectronics is to provide an interface between the biological world (blood pressure, electrocardiogram [ECG], and the like) and the electronics world (analog and digital hardware, software, and the like). This interface allows the characterization and quantification of the biological world, which can be used to gain further understanding of the fundamental biological processes being monitored. Alternatively, long-term monitoring of physiological parameters can lead to new and more effective diagnostic and treatment methods for particular medical conditions.

A typical interface between the biological and electronic worlds is shown in Figure 1.1. Here a suitable sensor or electrode is used to detect a biological parameter, and the resulting signal is then amplified and converted into the digital domain. Once this has been done, the signal can be transferred to a computer for long-term storage and processing. Depending on the application requirements, the data may be transfered over cables or via a wireless link.

Figure 1.1. A typical interface system between the biological world and the electronic world. Physiological parameters are sensed, amplified, and converted to digital signals, which can be stored and processed on a computer. Online signal processing, implemented in either the analog or digital domain, can be of significant use in enabling device miniaturization.

The biological world interface system thus includes everything from the sensor to the wired or wireless link. In many applications this system must be as physically small as possible, and capable of operating autonomously over long periods of time. This may be because data is being collected from a lab animal that is physically small, or because a human is being monitored, and they are expected to be going about their normal daily life. For this to be possible, the interface device must be unobtrusive, comfortable, socially acceptable, and long lasting.

Miniaturized, unobtrusive devices imply that only physically small batteries, which have limited energy storage and current sourcing capabilities, are available for use. Simultaneously, long-term monitoring implies that the limited energy capacity of the batteries has to exploited to the maximum by using very low-power electronics. Key for realizing these miniaturized interface systems is thus the optimization of the electronic design. For example, a system using only a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (ADC) produces much less data to transmit and leads to much lower overall power consumptions than systems using a 24-bit ADC. However, performing such optimizations inevitably requires detailed knowledge of the biological requirements for the given application, and obtaining these requirements is by no means trivial. As an example, consider the electroencephalogram (EEG), which records electrical potentials from the scalp.

Recommendations from the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology call for a 12-bit (72 dB) sampling resolution once the direct current (DC) component of the signal has been removed [1]. Most commercial EEG units use 16 or more bits, exceeding this recommendation. Typical analysis of the EEG produced, however, is performed by a human using 16 EEG traces displayed on a screen with 1024 vertical pixels. This gives just 6 bits of resolution [2]. For comparison, traditional paper-based EEG systems had a dynamic range of around 7 bits [2]. Potential room for optimization is thus present, especially if only automated analyses of the EEG are to be performed.

Of course, such uncertainties in the performance requirements are not confined to the biological world alone. For low-power, low-dynamic-range signal processing, analog circuit implementations can potentially significantly outperform their digital counterparts [3]. However, it is then necessary to contend with an amount of mismatch: for example, when implemented on a microchip capacitor values may be no more than 20% accurate, and no two transistors will be exactly the same. This leads to a variance in the performance of the analog circuit, and the range of this must be quantified to ensure that such a variance is acceptable. Accurate quantification of both the biological and electronic worlds is thus essential for optimizing the electronic design for device miniaturization.

One further method used to enable device miniaturization is online signal processing, as shown in Figure 1.1. As an example, if the EEG is being monitored, rather than transmitting the entire EEG recording it is possible to detect potential interesting sections of data online, and transmit only these sections. This significantly reduces the amount of EEG data to be sent, mitigating the use of high-power transmitters. However, accurate quantification is again necessary. It is essential that the accuracy of this data reduction method is known and acceptable. How many of the interesting sections are missed and how many false detections are made?

Unfortunately, in general bioelectronics applications, the quantification of online signal processing aiming to reduce the system power consumption, and hence the system size, is a problem subject to many constraints that make the algorithm design, implementation, and performance testing far from trivial. On the one hand, the algorithm must achieve acceptable performance accuracy for the given application. On the other hand, this must be done while developing an algorithm that can be implemented in very low-power circuits. There is no benefit in designing an algorithm that, when implemented, requires more power to operate than any potential power savings it provides. In addition to this, the potential for nonidealities in the end implementation, for example, from analog mismatch, must be accounted for.

The procedure for tackling this kind of problem is thus not to optimize any one aspect of it in isolation, but rather to look for a global solution that meets the constraints imposed by both the engineering design (such as the power consumption) and the biological application (such as a clinically acceptable detection accuracy) simultaneously. The overall interface design problem is thus an interdisciplinary one in which the bioelectronics designers must know the aspects of the biology that are going to condition the specifications of the electronic blocks; identify the best metrics to quantify performance for the given application; and devise a rigorous and representative test methodology that characterizes the performance within a certain confidence level.

Accurate characterization of the online signal processing algorithm is an essential part of this. For optimal power performance, these algorithms are best implemented as dedicated circuits, as opposed to in software. The circuit design, however, likely requires man-years of effort. For this not to be wasted on unpromising algorithms, accurate and reliable performance characterization is necessary at the algorithm design stage.

The aim of this chapter is to present the reader with examples of how to design a rigorous test methodology to characterize the performance of online signal processing systems designed to reduce the system-level power consumption. For example, what test factors need to be known and what performance metrics are best used in order to elucidate the most information possible about the performance? What is the impact of using different performance metrics, and how is it possible to ensure that the results are accurate and reliable? To illustrate the results on an actual algorithm, an EEG data reduction algorithm is considered. Nevertheless, although this algorithm is application specific, the methods and characterization routine are similar across many bioelectronics situations.

Section 1.2 thus presents the first part of the problem: the biological application and algorithm aim, in this case data reduction during monitoring of electrical brain activity (EEG). This motivates the need for an online signal processing stage and sets its engineering requirements. Section 1.3 then considers the factors that make representative performance testing nontrivial for this kind of application. Section 1.4 derives different performance metrics that could be used to characterize performance, discussing the advantages and disadvantages of each. Finally, Section 1.5 discusses the statistical testing of the results.

1.2 THE SIGNAL PROCESSING AIM

1.2.1 Introduction

The first step in the design of a rigorous test methodology for an online signal processing algorithm is the precise definition of the algorithm objective. This sets the required specifications for the algorithm, and also sets the objectives of the required test methodology. This Section quantifies the use of online data reduction in bioelectronics interface systems to decrease the system power consumption, and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PART I: HUMAN BODY MONITORING

- PART II: BIOSENSORS AND CIRCUITS

- PART III: EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

- INDEX