![]()

Part One

Nutrition and Health Considerations

![]()

1

Glycaemic Responses and Toleration

Geoffrey Livesey

Independent Nutrition Logic Ltd, Wymondham, UK

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Sugars and sweeteners have an important role in the human diet and choosing the right ones in the right amounts can influence health. Knowledge will enable good choices, and further research and understanding of the literature will confirm or deny how good our choices are, and where improvements are possible. Choice is not simply a matter of which is the healthier or healthiest, since the technological properties and economics of sugars and sweeteners impact on which of them can be used suitably in a particular food.

A wide range of potential influence on health is offered by sugars and sweeteners when selected appropriately, as will be evident in detail from other chapters. These include the following:

- A reduced risk of dental caries.1

- Potential for improved restoration of the early carious lesions.2

- A reduction in caloric value that may contribute towards a lower risk of overconsumption, obesity and improved survival.3,4

- Substrate for butyrate production, and potentially reduced risk of colon cancer.5

- The formation of osmolytes efficacious for laxation and lower risk of constipation or accumulation of toxic metabolites.6

- Substrate for saccharolytic and acidogenic organisms in the colon that contribute to prebiosis and ‘digestive health’ potentially including improved immunological function.7,8

Each of these can influence the choice of sugars and sweeteners. Of particular relevance is their impact on glycaemic response and potential to contribute to low glycaemic index (GI) or glycaemic load (GL) diets.

Lowering post-prandial glycaemia and insulinaemia through an appropriate choice of sugars9 and sweeteners,7 together with other low-glycaemic carbohydrates,10 fibre, protein, lower energy intake and exercise,11 can each improve glycaemic control. In turn, this appears to lower the prevalence or risk of developing metabolic diseases including metabolic syndrome, diabetes (and associated complications), heart disease, hypertension, stroke, age-related macular degeneration and certain cancers.12–16

In those who are susceptible, lower glycaemic carbohydrate foods may also benefit appropriate weight gain during pregnancy,17 limit insulin requirements in gestational diabetes,18 potentially allow favourable foetal growth patterns and fat accretion,19 reduce neural tube defects20 and aid recovery from surgery.21

Meta-regression of interventional studies of lower GI or GL diets show a time-dependent lower body weight over a 1-year period22 and supports weight maintenance after weight loss.23 Reduced food intake in humans4 may be partly responsible for weight loss and maintenance. Lowering of body weight improves survival among newly diagnosed diabetes patients,24 and may contribute to longer survival beyond old age as seen in animal studies while lowering glycaemia with isomalt.4

The converse of all aforementioned is that, given the right circumstances, a poor choice of type and amount of all carbohydrates, including sugars and sweeteners, could augment ill health. Attributes of sugars and sweeteners affecting health via the glycaemic response are nutritional and need to be seen in the context of the whole diet. It is appropriate, therefore, to consider the glycaemic aspect of diet and health from ancient to the present and future times – so far as these can be ascertained, explained and envisaged.

1.2 GLYCAEMIC RESPONSE IN ANCIENT TIMES

It is often argued that our genes might not cope with diets that are substantially different from those eaten by our ancestors.25–30 Quite what these diets were or how tolerant ancient genes have become are matters of uncertainty. Successful genes were in existence for both herbivorous and carnivorous diets prior to humankind; however, no early diet appears to have been high glycaemic. Those peoples who would normally consume ‘early’ or rudimentary diets, such as recent hunter–gatherers, experience low levels of diabetes and respond adversely to diets we may now consider high glycaemic.26,31 This is consistent with the notion that early genes were unadapted to high-glycaemic responses, and also consistent with a notion of adaptation having occurred in the people of today's relatively more glucose-tolerant ‘western’ cultures, at least among a large proportion of them. Those not having adapted, contribute to prevalent diabetes and other conditions mentioned that are currently experienced, which is far higher than in either hunter–gatherers or rudimentary horticulturalists or simple agriculturalists or pastoralists.26 For the people of these ‘basic’ cultures and for ‘unadapted’ westerners (easterners or southerners or northerners), a high-glycaemic response remains a health hazard, for which a variety of strategies exist to help them cope.11 Europe has a rich culture and a documented history of its foods, and so we can obtain some idea of how the glycaemic character of diets may have developed over time.

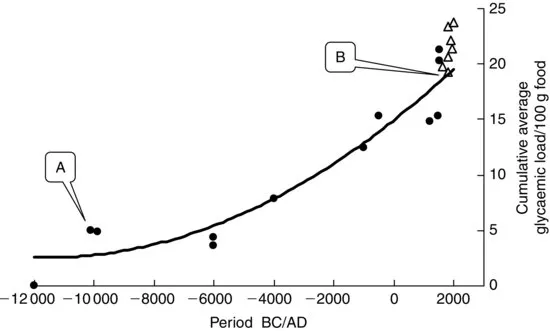

Generally, we may assume diets to partly reflect the foods that can be found or are made available to eat. If this is so, examination of the inventory of foods identified in European history may shed some light on what was eaten and what might now be eaten for optimal health. Such an inventory is provided by Toussaint-Samat32 from which an assessment of the development in the glycaemia character of contemporary diets has been made taking account of the protein, fat, fibre and sources of carbohydrate (Figure 1.1). The picture cannot be accurate but what is clear is a progressive increase in the GL, with a markedly rapid increase in this GL following industrialisation. We cannot be sure of the prevalence of disease in Europe throughout the whole of this timescale, but we would not likely dispute that the prevalence of obesity and metabolic disease is as high now as ever.

Such a trend is argued to also have occurred throughout more recent times in the United States,25 with recent emphasis on reducing the fat content of the diet, a doubling of flour consumption during the 1980s and an increase overall in sugar, corn syrup and dextrose consumption prior to the end of the millennium.33–35 These together with a lower dietary fibre content of foods34 imply exposure to diets eliciting a high-glycaemic response.

1.3 GLYCAEMIC RESPONSE APPROACHING THE MILLENNIUM

Much of our understanding of the interplay between health and the glycaemic response to foods has arisen from investigations into the dietary management of diabetes. Whereas very low-glycaemic carbohydrate foods such as Chana dahl were used in ancient India for a condition now recognised as diabetes,36 nineteenth century recommendations in western cultures were for starvation diets, which were, of course, non-glycaemic. The drawback of such is obvious and in 1921, high-fat (70%) low-carbohydrate (20%) diets were recommended,37 which by definition would be low glycaemic. A gradual reintroduction of carbohydrate into recommendations for diets for diabetic patients arose as carbohydrate metabolism came under some control using drugs, but mainly because ‘dietary fat’ was recognised to have a causal role in coronary heart disease, to which diabetics and glucose intolerant individuals succumb, more readily in some cases than others.38–41 The metabolic advantages of replacing dietary fat (saturated fat) with high-fibre high-carbohydrate was lower fasting glycaemia, lower total-, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol and lower triglycerides.42–46 Such benefits may in part be related to dietary fibre or its influence on the glycaemic response.47,48 Certainly, the non-digestible carbohydrate in these diets would ensure some degree of lower glycaemia for a given carbohydrate intake and support beneficial effects from lower saturated fat intake.

During these times, the adverse influence of higher glycaemia or more dietary carbohydrate was either unrecognised or the risk was accepted by the medical profession in fear of (or compromise for) the adverse effects of ‘dietary fat’. The adverse influence of higher glycaemia may also have been overlooked due to the apparent benefits of the non-digestible carbohydrate in the high-carbohydrate foods. Indeed, the Institute of Medicine has recommended high-fibre diets to combat coronary heart disease,49 and this builds upon the dietary fibre hypothesis that proposed higher prevalence of diabetes, heart disease and other conditions associate with diets deficient of fibre.50,51 An absence of fibre in high-sugar pro...