![]()

PART I

CONTEXT

![]()

Chapter 1

History of Industrialized Building

“Three things you can depend on in architecture. Every new generation will rediscover the virtues of prefabs. Every new generation will rediscover the idea of stacking people up high. And every new generation will rediscover the virtues of subsidized housing to make cities more affordable. Combine all three—a holy trinity of architectural and social ideals.”1

—Hugh Pearman

Prefabrication architecture is a tale of necessity and desires. Individuals and communities have constructed shelter from the beginning as a matter of function. In order to build in remote locations, deliver buildings more quickly, or to build in mass quantity, society has used prefabrication, taking the construction activities that traditionally occur on a site to a factory where frames, modules, or panels are fabricated. Barry Bergdoll, curator of the Museum of Modern Art 2008 “Home Delivery,” an exhibition that tracked developments in prefabricated housing, differentiates prefab from prefab architecture. He states that prefab is a “long economic history of the building industry that can be traced back to antiquity” including the methods employed to build ancient temples and timber structures. Conversely, the history of prefab architecture is “a core theme of modernist architectural discourse and experiment, born from the union of architecture and industry.” 2 The relationship between need and desire in studying prefabrication is argued as follows: If industrial-manufacturing processes can produce other products and goods for society, then why can’t the same process be harnessed to produce higher quality and more affordable architecture?

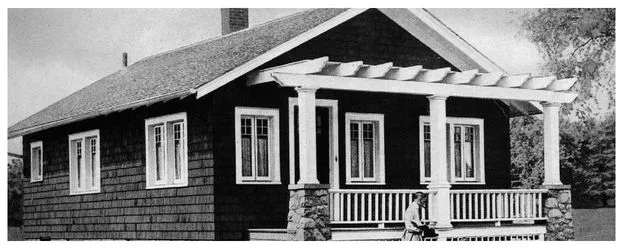

Figure 1.1 This table illustrates the historical influences on the development of prefabrication. The value on the influence bar indicates the relative impact. White:—little to no impact; Gray—impact; Black—large impact. Note that many of the influences occur in the latter part of the 20th century with the large majority from 1960 onward.

Although not to the extent of other industries, prefabrication has already been realized in many buildings; but can architecture, a discipline rooted in image, exploit the principles of offsite fabrication to make itself more relevant? Can prefabrication be a tool by which architecture can have an impact on all areas of the built environment including and most importantly housing? How might the quality of both design and production concurrently be increased? These are questions that the early and late modernists—Le Corbusier, Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Wright—as well as design engineers—Fuller and Prouve—have asked. These are the questions architects today including KieranTimberlake, SHoP, Michelle Kaufmann, and others are asking. In order to answer these questions, we will step back and evaluate the historical linkages between industrial manufacturing processes and the production of architecture to understand the context by which we find architecture today and to uncover the lessons learned from previous attempts in prefab architecture.

This chapter reviews the developments in industrialized building that shape our understanding of prefabrication in architecture and building. Chapter 2 will evaluate the relationship between the history of the architectural profession and prefabrication, uncovering the failures and successes. It will end with a summary of lessons learned from failed prefab experiments that may be applied to reassessing the future of prefab architecture in the twenty-first century. The techniques developed in other industries have been transferred to the construction sector to provide more appropriate production solutions to creating shelter. In addition to technology transfer, many societal and cultural factors have affected the development of prefab architecture.

1.1 British Contributions

The history of prefabrication in the West begins with Great Britain’s global colonization effort. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, settlements in today’s India, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States required a rapid building initiative. Since the British were not familiar with many of the materials in abundance in these countries, components were manufactured in England and shipped by boat to the various locations worldwide. The earliest of such cases recorded was in 1624, when houses were prepared in England and sent to the fishing village of Cape Anne in what is now a city in Massachusetts.3 The late 1700s and early 1800s was a time of Australian settlement by England. It is reported that the earliest settlement in New South Wales was home to a prefabricated hospital, storehouses, and cottages that were shipped to Sydney arriving in 1790. These simple shelters were timber framed and had timber panel roofs, floors, and walls. Speculation also suggests that infill material could have been canvas or a lighter timber frame infill system with weatherboarding. A similar system is reported to have been unloaded and erected a couple of years later in Freetown, Sierra Leone, to build a church, shops, and several other building types.4

English colonial building extended to South Africa. In 1820 the British sent a relief mission of settlers to South Africa, Eastern Cape Providence, accompanied by three-room wooden cottages. Gilbert Herbert writes that the structures were simple and shed-like, with precut timber frames, clad either with weatherboarding, trimmed and fixed on the site, or with board-and-batten siding. Door and window sashes were probably prepared as complete components.5 These structures were not as extensively prefabricated as our contemporary understanding of offsite fabrication; however, they represent a significant reduction in labor and time compared to onsite methods that preceded. The prefabricated shelters’ timber frame and complex joints were structurally and precision dependent on offsite methods.

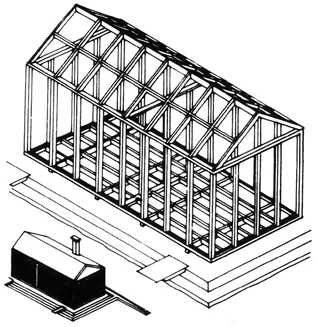

1.1.1 Manning Portable Cottage

H. John Manning, a London carpenter and builder, designed a comfortable, easily constructed cottage for his son who was immigrating to Australia in 1830. Later known as the Manning Portable Colonial Cottage for Emigrants, the house was an expert system of prefabricated timber frame and infill components. It is described by John Loudon in the Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture as consisting of grooved posts, floor plates, and triangulated trusses. The panels of the cottage fit between the grooved posts, standardized and interchangeable. 6 The system was designed to be mobile, easily shipped for furthering the colonial agenda of the British. Manning stated that a single person could carry each individual piece that made up the shelter. The Manning Cottage was an improvement of the earlier frame and infill systems designed by the English in that it offered an ease of erection. The system was simply bolted together with a standard wrench, appealing to the abilities and availability of tools to the emigrants. Herbert writes, “the Manning system foreshadowed the essential concepts of prefabrication, the concepts of dimensional coordination and standardization.” 7 Manning’s system used the same dimensional logic with all posts, plates, and infill panels being carefully coordinated. It built upon the need for a quick erection system for emigrants but relied upon the British carpentry skills in shipbuilding.

The Portable Colonial Cottage made its way to many settlements by the British throughout the nineteenth century. Its impact on the British-settled North America and the future U.S. construction industry is uncertain, however, it is assumed that the practices of timber architecture from Britain were the beginnings of the balloon frame in the United States. Augustine Taylor is often credited with the invention of the balloon frame in its implementation in construction of St. Mary’s Church in 1833 in Fort Dearborn near Chicago. The light frame, including the platform frame and balloon frame, resulted from two primary factors: a plentiful supply of wood in the new country and a rapidly expanding industrial economy with mass-produced iron nails and lumber mills. In the span of one spring and summer, 150 houses were built. Buildings were erected so quickly that Chicago was almost entirely constructed of balloon frames before the fire of 1871. The infamy of the speed of balloon frame construction preceded the building of the entire West, mostly in light wood construction.8

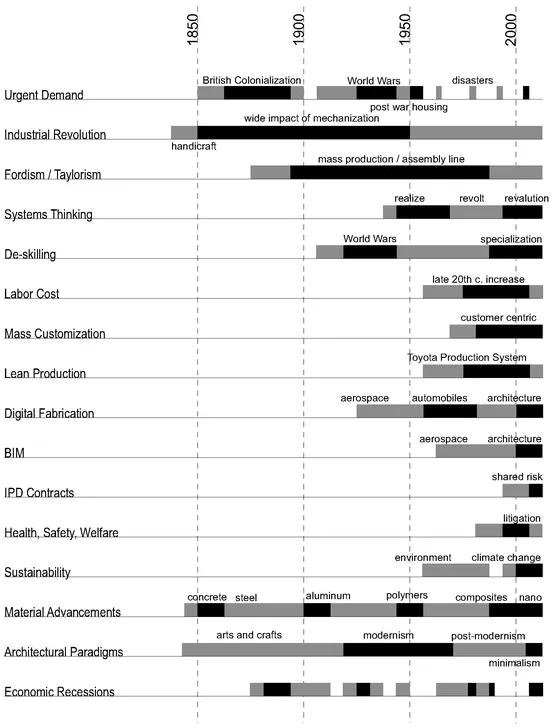

Figure 1.2 The Manning Portable Colonial Cottage for Emigrants was a timber and panel infill prefabricated system. Developed by Manning, this was a quickly deployable solution to the rapidly expanding British colonies in New Zealand and South Africa during the nineteenth century.

1.1.2 Iron Prefab

Another contribution that came out of the British colonial movement was the employment of iron manufacturing for building construction. Components such as lintels, windows, columns, beams, and trusses were manufactured in a foundry and fabricated in a workshop. 9 The components were brought to the jobsite and assembled into structure and enclosure systems. Like its prefabricated timber-framed counterpart, iron construction was not as extensive as prefab today, but fathered the beginnings of the steel structural movement in the United States and elsewhere.

One of the first employments of iron construction in the United Kingdom was in bridge building. The Coalbrookdale Company Bridge in 1807 was almost entirely prefabricated and erected in pieces onsite. This was followed by a host of bridges in England that progressively streamlined the process of production and erection. Pieces were standardized, cast repeatedly, and shipped to the site to be erected by fewer laborers and unskilled laypersons garnering a saving in time and cost in comparison with the traditional construction of handcrafted wood or masonry. Some of the better-known bridges were on the Oxford Canal made at the Horseley Iron Works, at Tipton, Staffordshire. John Grantham reports that this foundry was also the first to produce an iron steamboat. The ships were constructed of heavy plates riveted together to form units. The ships could be assembled, disassembled, and reassembled. One of these manufacturer/fabricators was William Fairbairn, who in the mid-1800s built four “accommodation” boats, now known as cruise ships. This technology was transferred and Fairbairn later built a prefabricated iron plate building. In the mid-1800s English lighthouses and other building types were constructed using prefabricated iron plates and rivets.10

Cast iron construction, the precursor to contemporary structural steel construction, used mass-produced cast components that were envisioned as a kit-of-parts. By standardizing manufacturing, the economy of scale helped realize a savings in time and cost. The technology was primarily used as a frame and could be turned into any stylistic expression including Gothic or Baroque. In addition to the bridges, ships, lighthouses, and prosaic buildings, the single most extensive use of the material was in the standardized structure and infill enclosure of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in England, otherwise known as the Crystal Palace. The structure was largely a repetitive system of standardized components that when assembled created a massive skeleton. Joseph Paxton, the project’s designer, had a background in green house design and claimed,

“All the roofing and upright sashes would be made by machinery, and fitted together and glazed with great rapidity, most of them being finished previous to being brought to the place, so that little else would be required on the spot than to fit the finished materials together.”11

The palace was certainly not the first in cast iron architecture, nor the last, but it linked the Manning Cottage precut timber frame with the new material of the day, cast iron. The large number of factory-produced components and the details of the Palace are quite astonishing considering the era in which it was realized. In addition, the Crystal Palace is important because it represents a shift in understanding among architects, that beauty may be as simple as the functional means of production. Paxton was more interested in the engineering, fabrication, and assembly process, than in traditional aesthetic references.

1.1.3 Corrugated Iron

The early 1800s also ushered in an additional innovation in metal: corrugated iron. Although prefabrication of frames was relatively well developed in the early part of the nineteenth century, panel and spanning material were underdeveloped. The Manning Cottage and iron trusses of prefab buildings used traditional canvas or wood planking as a means of roofing. Corrugated iron provided a quickly constructed, affordable, and structurally efficient material for roofs and walls. Corrosion obviously presented problems until 1837 when many companies began to hot-dip galvanize metals in order to protect them. Richard Walker, in 1832, noted the potential for corrugated iron for portable buildings intended for export. The corrugated sheet could be nested in multiple layers during transit and were cut into 3 ft × 2 ft panels that easily could be handled by one person, and fas-tened into place at the jobsite. Along with Manning’s Portable Cottage, Walker’s marketing and exportation of corrugated iron provided one of the first wide...