- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conservation in the Age of Consensus

About this book

This new text on the subject of conservation in the built environment provides a unique holistic view on the understanding of the practice of conservation connecting it with wider societal and political forces. UK practice is used as a means, along with international examples, for bringing together a real understanding of practice with a social science analysis of the issues. The author introduces ideas about the meanings and values attached to historic environments and how that translates into public policies of conservation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conservation in the Age of Consensus by John Pendlebury in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Conservation, culture and planning

Introduction

A study of conservation made in different historical periods would inevitably throw up quite different themes and emphases. So, for example, a cursory look at books produced on conservation in the early to mid 1970s would reveal books with such emotive titles as Goodbye Britain (Aldous 1975) and The Rape of Britain (Amery and Cruikshank 1975). Just reading these titles would suggest that conservation was, at the time, a contentious and hard-fought-over issue. It seems, writing in the mid 2000s, however, that perhaps the key characteristic of conservation in the thirty or so years since is how accepted it has become. Inevitably there is always ‘surface noise’, for example, debate about the extensiveness of protection of the historic environment, complaints about, and fears for, resources and individual cases to contest. However, that the conservation of the historic environment should be an important goal of public policy is generally accepted as a given. Such challenges that do occur to this basic premise are so unusual as to be regarded as iconoclastic. This consensus evolved through strife-torn development struggles in the 1960s and 1970s and the heritage-drenched 1980s and has endured into a new political era where terms such as ‘new’ and ‘modernising’ have been greatly emphasised. On the face of it this is ‘the age of consensus’. What I seek to do in this book is examine and look beneath the surface of this apparent consensus. I look at what sort of activity conservation is and how its application to our towns and cities has evolved. I look at some of the ways that the nature and purpose of conservation have developed and changed and what its role is in contemporary society. Part of this discussion involves examining the function built heritage plays in society. I do this principally with reference to the United Kingdom, and often specifically England, although my discussion sometimes extends much further afield.

My particular principal concern is the protection and management of the historic environment by the national and local state. Within this I have a particular interest in the conservation of places, rather than, say, a focus on grand individual monumental buildings. The way protection and management of such places occurs is through the planning system.

Planning and protection

Within the sphere of the historic environment one can make a binary division between those heritage sites that are usually visited and experienced for their qualities as heritage and the ‘other’. In the former one might include country houses cared for by the National Trust and ruined castles in the guardianship of English Heritage, as well as other places beyond the scope of this book, such as museums acting as repositories of cultural artefacts. Though I will occasionally touch upon heritage sites, my concern is more with the other: the historic environment that is experienced as part of everyday life. This includes a whole range of buildings and environments officially labelled as historic, from major architectural compositions to the commonplace and even mundane. There are few places in Britain where the conservation of this heritage is not a significant issue. With around 500 000 listed buildings, 9000 conservation areas and 20 000 scheduled ancient monuments in England alone, it is a patrimony that extends the length and breadth of the country. Listing encompasses, for example, the grandeur of Bath, where the whole city is also inscribed as a World Heritage Site, and a pigeon cree in Sunderland. Conservation areas are designated around the internationally important and renowned towns and cities such as Bath, York and Chester and much more modest elements of the heritage such as former colliery villages and ‘Metroland’ suburbia, as well as such unusual designations as the Settle-Carlisle Railway line (see Figure 1.4) and areas of field barns and walls in the upland countryside of the Yorkshire Dales. The sheer extensiveness of the protected heritage means that it is also subject to considerable ongoing change. This is not a heritage of castles and standing stones that can be ‘preserved as found’. It covers hundreds of thousands of buildings that people live in and areas that are subject to major economic change.

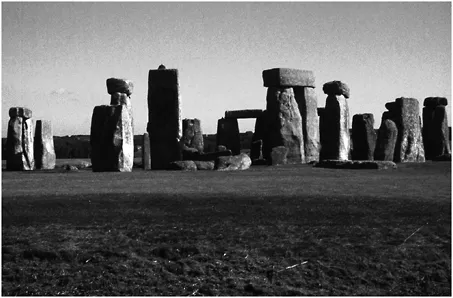

1.1 The protected heritage: Stonehenge, part of a World Heritage Site and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Source: author.

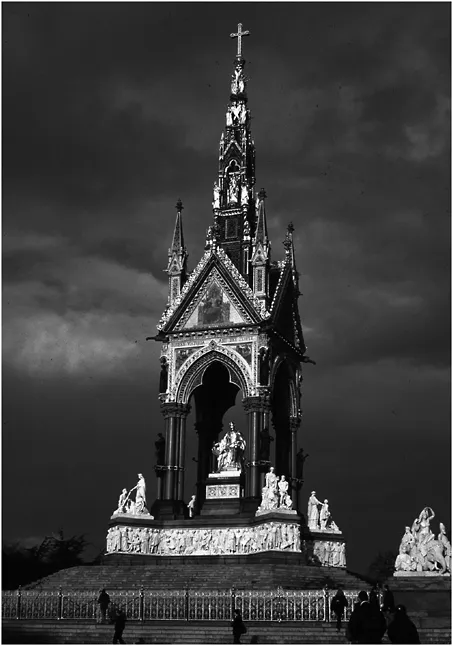

1.2 The protected heritage: The Albert Memorial, a Grade 1 listed building and symbol of national identity.

Source: author.

The evolution of the relationship between conservation and planning is the focus of Chapters 3, 4 and 5 of the book. These three chapters are not an attempt at an even history: I focus on issues and events that are of especial relevance to the story I wish to tell. Nor do they give a detailed history of changes in legislation and public policy such as that given admirably in other books such as (Delafons, 1997a). Although the first conservation legislation in Britain dates back to the 1882 Ancient Monuments Act, it is in the post-Second World War period that the conservation-planning system as we know it today began to really evolve. For example, the Town and Country Planning Acts of 1944 and 1947 introduced the system of listing buildings. However, of equal relevance was the way that town planners began to become seriously engaged in the planning of existing towns and cities at this time, rather than being predominantly concerned with the layout of new development. The 1940s produced a series of remarkable ‘advisory plans’ or ‘reconstruction plans’. In the case of historic cities these sought to reconcile sustaining character with the pressures of the modern world. Since the ‘reconstruction plans’ of the 1940s there has been an ever closer relationship between conservation and planning, sometimes fractious, sometimes harmonious. By the end of the 1960s conservation issues had started to assume the centre ground. Chapter 3 charts this evolution.

1.3 The diversity of the protected heritage: listed public urinals, Rothesay, Isle of Bute.

Source: author.

1.4 The diversity of the protected heritage: the Ribblehead Viaduct, part of the Settle-Carlisle Conservation Area, some 76 miles (122 km) long.

Source: author.

Chapter 4 moves the story into the 1970s and the seismic shifts of that period as development struggles were fought up and down the country and as the economy and property markets collapsed. It was a period of intense polemical activity, as noted at the beginning of this chapter, and conservationists fought for their cause both within and outside the machinery of the state. Gains were won by utilising, expanding and strengthening state protection through listing and the system of conservation areas, introduced in 1967. The European Architectural Heritage Year of 1975 was perhaps a high-point of the decade; towards of the end of the 1970s there were concerns that the conservation movement’s achievements were endangered by governmental indifference and economic austerity.

Chapter 5 focuses on conservation during the Conservative governments in the 1980s and 1990s. It was during this period we can say that we arrived at the Age of Consensus. Ironically perhaps, it was during this period of government known for economic liberalisation that conservation became firmly established as a key element of planning policy. I document how conservation strengthened as a national policy objective in this period and some of the reasons why this might have been the case and go on to describe how contestation in the planning system effectively shifted from whether to conserve to how to conserve and develop historic areas.

Conservation has become a policy objective of central importance within the planning system in a way that would have been barely recognisable in earlier periods. However, it is worth noting that at the same time there has been tremendous continuity in the framework within which protected heritage is defined and in terms of the basic principles which government advises should apply to its management (Pendlebury 2004). The legislative definitions for listed buildings and conservation areas remain unchanged, since 1944 and 1967, respectively. The primary criteria for listing buildings have endured, focusing on architectural interest, historical interest, historic associations and ‘group value’, albeit these have been applied more and more generously. Similarly there is much continuity in the basic principles that have underpinned policy guidance on the historic environment since the first significant national guidance started emerging in the late 1960s, though again this has been within a context of conservation assuming more policy importance.

There is therefore tremendous continuity in the basic principles that define the historic environment and the way government considers it should be managed, since the late 1960s/early 1970s. These derive from a justification for conservation based upon cultural values relating to architectural quality, historic importance and archaeological significance: to defining places as special. However, what has shifted fundamentally in official pronouncements during this period is the benefits that are argued to derive from this activity. An official document such as Preservation and Change (Ministry of Housing and Local Government 1967) set out brief statements of the value of conservation relating to beauty and visible history. In the 1970s there was rhetorical emphasis on the social value of conservation, and in the 1980s stress on its economic potential. By the time of the government’s policy advice document PPG15 (Department of the Environment and Department of National Heritage 1994) benefits were argued to include value in terms of national identity, quality of life, local distinctiveness, leisure and recreation and economic prosperity. Force for Our Future, a more recent government statement on the heritage was even more fulsome. It waxed lyrically and extensively about the role of conservation in establishing environmental quality and identity, local distinctiveness and continuity and as an active part of social processes, including community cohesion and social inclusion, and as a stimulus for creative new architecture (Department of Culture, Media and Sport and Department of Transport Local Government and the Regions 2001 a). Furthermore, conservation was held to aid economic processes and economic regeneration in particular.

However, despite these sweeping statements, these are benefits that may (or may not) follow decisions to protect based upon essentially traditional criteria of specialness, and where guidance on conservation management decisions emphasises first and foremost the importance of sustaining cultural worth defined around issues of fabric and aesthetics.

The next section briefly introduces some conceptual assumptions used in this book.

Heritage, conservation and culture

A starting premise of most recent study of the concept of heritage suggests that its nature is not as a static inheritance to which fixed and enduring values are applied. Rather, for objects to be identified as heritage requires a process of identification, or ‘heritage creation’. The establishment of value, however ‘value’ is defined, is central to the act of conservation; societies only attempt to conserve the things they value. In addition, the very act of conservation gives a building, object or environment cultural, economic, political and social value. Concepts of cultural, historical or social value are culturally and historically constructed; thus value is not an intrinsic quality but rather the fabric, object or environment is the bearer of an externally imposed, culturally and historically specific meaning that attracts a value status depending on the dominant frameworks of value of the time and place. Inherent in this is the idea that when we refer to the heritage we are talking about the contemporary use of the past. Heritage becomes a fluid phenomenon rather than a static set of objects with fixed meanings. Smith (2006) has taken this argument to its logical conclusion by arguing that there is no such thing as material heritage; heritage is essentially a cultural practice and social process.

Conservation of such heritage is in turn a bundle of processes, encompassing the political, cultural, social, economic and so on (Avrami et al. 2000). This may include the idea of conserving the fabric of the past for future generations, historically a strong principle in the field of architectural conservation. Privileging some element of the past as heritage over another necessarily involves a socially constructed process of selection. As what constitutes heritage is contingent on prevailing cultural, political and economic mores it is also inherent that what constitutes heritage can be contested. For example, different social or economic groups in a society may have quite different ideas both about what heritage is and how it should be managed. Furthermore, different groups may have radically different interpretations of, or lay claim to, what is ostensibly one piece of material heritage.

Heritage identification and creation are complex processes, and decoding precisely how and why this happens may be very difficult. However, if we accept that heritage is not ‘just there’, but that an active process of identification and labelling occurs, then we can assume that this takes place for a purpose. Usually the idea of heritage is linked to cultural concerns (though the economic and social functions of heritage have become increasingly significant factors, as I will discuss). Developing from Williams’ (1976) landmark discussion of culture, Mitchell held culture to be the patterns and differentiations of people, the way these develop and the way these mark off different groups (Mitchell 2000). It is also the way these patterns, processes and markers are represented and the way people organise these into hierarchies of significance or importance. Culture is thus a reflexive act of definition from inside or outside particular groups; in other words, culture is socially produced.

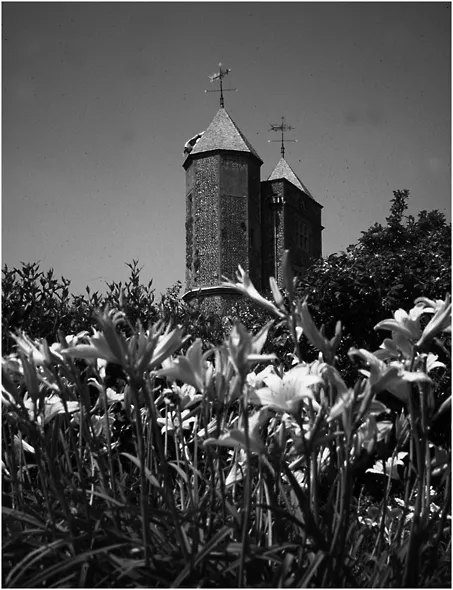

1.5 The wider historic environment: Sissinghurst, Kent; Grade 1 in the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

Source: author.

This definition applies usefully to the way that cultural heritage is defined. It is a medium through which identity, power, and society are produced and reproduced. Furthermore, cultural heritage is the heritage of somebody and thus, it has been forcibly argued, not the heritage of others (Tunbridge and Ashworth 1996). The historic environment is thus one manifestation of a particular set of markers of culture that has a variety of functions. For example, as discussed in Chapter 2, the very development of systems of heritage protection was intertwined with narratives of nationhood and the creation of the modern nation state, giving an explicit political function to the historic environment. Definitions and delineations of heritage emerge through debate, negotiation and struggle between different interests at a range of geographic scales. Heritage is rarely, if ever, ‘neutral’ and politically can be used for good or ill.

The idea of heritage extends far beyond the confines of built heritage or the historic environment. Despite Smith’s recasting of heritage noted above, a common binary division is made between material and intangible heritage, the latter encompassing traditions, folk songs and so on. Material manifestations of heritage are again enormously diverse, including, for example, any of the vast range of objects that might be found in museums. This book focuses on a particular subset of this material heritage, historically known as the architectural or monumental heritage, historically reflecting a relatively discrete focus on major buildings and prehistoric monuments. However, as remarked upon above, heritage definition and conservation activity have undergone a phen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword and acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: conservation, culture and planning

- 2 Modern conservation

- 3 Policies and plans: the development of state intervention

- 4 The 1970s: shifting ground

- 5 Conservation, conservatives and consensus

- 6 The commodification of heritage

- 7 Conservation and the community

- 8 World heritage

- 9 Postmodern conservation

- 10 Conservation reformed

- 11 Conservation and the challenge of consensus

- References