![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Teams

During the 1980s, the space shuttle program was NASA’s major thrust. Shuttles launched, carried astronauts to space, and then returned like airplanes, landing on a runway. The liftoff of the space shuttle Challenger on January 28, 1986 seemed typical of the many other successful shuttle flights. There were seven astronauts aboard the shuttle, including for the first time a person who was not trained as an astronaut, a teacher, Christa McAuliffe. Several seconds before liftoff, the shuttle engines ignited properly as they should have. At liftoff time, all three main engines were firing as the members of the team at NASA expected them to. Soon, the shuttle left its pad and cleared the tower. Its initial ascent was as predicted, showing nothing that caused anyone to have unusual concerns. This looked like any typical shuttle launch and another success for NASA.

Unfortunately, it did not turn out to be a typical liftoff. At 73 seconds into the launch the Challenger rapidly disintegrated, virtually exploding, and all seven astronauts aboard were killed as a result, including the person who NASA had billed as the first teacher-in-space. Why did the Challenger break apart? The simplest answer is also technical one. In short, it resulted from an engineering failure of the solid rocket boosters. Morton Thiokol was the supplier of these solid-rocket boosters. On the morning of the launch, the air temperature was unusually cold – 31 degrees Fahrenheit – which is far lower than is typical for Florida for that time of year. As a result of this low temperature, the O-rings in the boosters failed to seal properly, and caused a leak which quickly developed from a small plume into a full break up within a time period of just over a minute. This would appear to blame the explosion on a complex engineering issue that NASA could not have foreseen.

Although the surface cause certainly did result from an engineering failure, the root cause requires one to delve into the group dynamics of NASA. As subsequent investigations revealed, Morton Thiokol and NASA had definitive evidence of this potential failure long before the fateful morning of the explosion. One engineer even wrote a memo suggesting that a failure like the one in the Challenger could lead to a loss of life. NASA even had ample opportunity to cancel the launch during several discussions with Morton Thiokol, the supplier of the rocker boosters. However, the key decision makers ignored these concerns and went forward anyway with the launch. Janis (1982) attributes this failure to a faulty group decision-making process, which he termed Groupthink (this is covered in more detail later in this book). Janis provides detailed evidence of how Groupthink is likely to have caused the Challenger disaster. Furthermore, Janis provides detailed methods designed to intervene in small groups such as NASA’s launch team so as to help prevent these poor decisions. As a result of the Challenger disaster, NASA instituted several changes to help the launch team avoid a similar future disaster, some of which were even similar to those suggested by Janis. Did they work? In 2003, the astronauts in the space shuttle Columbia unfortunately faced a similar fate, though this time during reentry rather than at liftoff. Some scholars blame the Columbia disaster on the same symptoms of Groupthink that once again occurred at NASA (Ferraris & Carveth, 2003).

So, can teams be successful? The evidence is mixed. Some believe that teamwork can help organizations to perform beyond their expectations. Others are not so confident about the benefits of teamwork. Regardless of your bias, this book should help to provide you with a basic understanding of the way groups work and some tools to help you to make them work better.

Learning Goals for Chapter 1

- Differentiate a group from a team.

- Understand the importance of groups and teams in organizations today.

- Understand the nature of groups and teams in organizations today.

- Understand the goal of synergy and the reality of most teams.

- Know the input-process-output model of group functioning.

What Is a Group, What Is a Team?

One of the first questions with regard to understanding teams is to determine what a team is and how it differs from a group of people. A group can be defined as “two or more individuals who are connected to one another by social relationships” (Forsyth, 2006, pp. 2–3). This definition can be divided into its parts. The first part focuses on two or more individuals, meaning that groups can range from very small to very large. The second part of the definition is that there are members who are connected to each other, meaning that the members are somehow intertwined or networked. The third part, by social relationships, emphasizes the social nature of groups, regardless of their emphasis. In summary, members are seen and see themselves as part of the group because of their connected relationships.

On the other hand, a team can be defined as “an organized, task-focused group” (Forsyth, 2006, p. 159). This definition focuses more on the structure of the group and the task that the group is performing because teams, especially those in the workplace, have specific task requirements which the organization expects members to complete and are structured in a way that should help them meet those goals. A second concept that helps to distinguish the difference between some groups and teams is entiativity (Campbell, 1958), or the level of “groupness” among members; teams have high levels of interaction, interdependence, and belongingness that is typical of groups with high entiativity. It is this combination of structure, task focus, and high entiativity that typically distinguishes a team from any other group.

Katzenbach and Smith (1993; 2005) break down the differences between groups and teams even further. According to their classification system, a group includes the following:

- a strong, clearly focused leader;

- a system of individual accountability;

- a purpose that is the same as that of the broader organizational mission;

- outputs that are based on individual rather than collective work products;

- an emphasis on running efficient meetings;

- a system where members measure the group’s effectiveness indirectly by its influence on others (such as financial performance of the business); and

- discussions where the group makes decisions and then delegates responsibility to members or others.

On the other hand, a team includes the following:

- a process of sharing leadership roles;

- a system with both individual as well as mutual accountability;

- a specific purpose that the team itself determines;

- outputs that are based on collective rather than individual work products;

- an emphasis on open-ended discussion and active problem-solving during meetings;

- a system where members measure the team’s performance directly by assessing collective work products; and

- discussions where the group makes decisions and then does the real work together.

As can be seen in all of these definitions, there is overlap between what is a group versus what is a team. Although there is disagreement about the specific definitions (see Forsyth, 2006 for an excellent summary of this debate), I conclude that a team is a specific type of group, though a group is not always a team. There are many different social groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous support groups, that may be high in interdependence but cannot be classified as a team because they do not have the task focus that is expected of teams. On the other hand, there are no teams that cannot also be classified as groups. One of the reasons to consider the nuances of these definitions is that there is considerable research about small groups, only some of which applies directly to teams. The rest of the research may or may not be generalized to teams – it is the reader who must carefully make that determination.

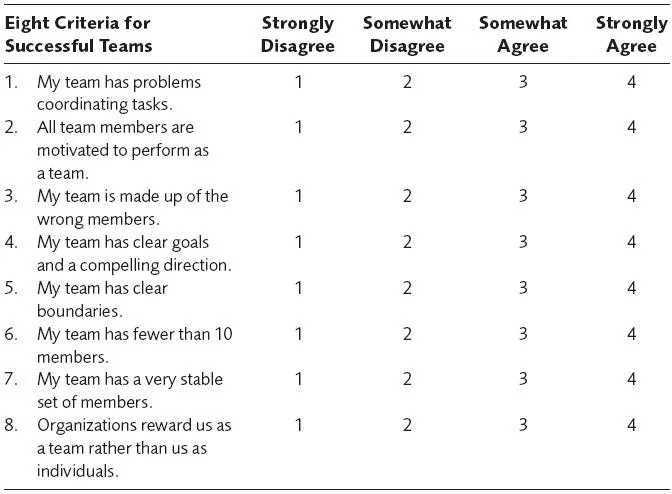

Team assessment: Are we a successful team?

The following questions are based on recommendations from Hackman (Coutu & Beschloss, 2009). Answering these questions can help you to quickly determine whether your team may or may not be as successful as it should be (Table 1.1).

This quick assessment can help you to assess how well your team is doing. Scores can range from 8 to 32. If your team scores closer to eight, your team is likely to be facing considerable issues with members and how they work together; its performance is definitely suffering and it is likely a detriment to the organization. If your team scores closer to a 32, it is likely to be helping the organization succeed. Scores in the middle represent teams that can improve performance but may not be holding the organization back.

Teams in Organizations Today

As the previous space shuttle example illustrates, teams work together to send shuttles to the moon. They also operate on people, determine how to fight wars, decide who to hire for a position, and set the strategy for multinational corporations. In fact, organizations today require groups and teams to make far more decisions and perform many more tasks in organizations than ever before (Devine, Clayton, Philips, Dunford, & Melner, 1999; Guzzo & Shea, 1992). Furthermore, groups and teams at work are unlikely to go away any time soon (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006) because teams separated by time and distance can continue to function well with the rapid increase of technology that enables computer-mediated team meetings; individuals are expected to work in teams, and organizations expect greater outcomes from increasing their use of teams.

There are many reasons why people in organizations would want to work in teams (for a comprehensive list, see Zander, 1985). Five of the more common of these reasons include:

- Preferences for Social Interaction. Most people are social by nature and thus are attracted to working with others. A team provides them with this opportunity (Parks & Sanna, 1999).

- Dividing Work. Many tasks need to be completed quickly so as to provide organizations with a competitive advantage. However, these tasks can be very complicated and difficult for one person to complete in a timely fashion. It is much easier for team members to divide work among multiple people so that they can accomplish a greater volume of work at a faster rate (Stewart, Manz, & Sims, 1999).

- Working Collectively to Effect Change. Individuals often come together to plan and implement change when they think that any “one person acting alone cannot create that change” Additional members will continue to join if the group has a clear purpose with which they agree (Zander, 1985, p. 1).

- Information Sharing. Many complex problems require input from multiple individuals, and team members often know that they do not have the information that they need to solve these problems. Multiple members provide team members with the opportunity to increase the level of information and expertise on which to draw when compared with working alone (Franz & Larson, 2002).

- Organizational Buy-In. One important step to succeeding during an implementation phase is to get buy-in within all levels of an organization. Team members expect that decisions made with their participation get better buy-in among organizational members and improved commitment than will any individual decisions made by management (Scanlan & Atherton, 1981).

Although these factors affect what team members expect to get out of working in teams, they do not fully explain why most organizations have fully embraced teamwork. Social interaction, for example, is helpful to the individual members in a team. However, organizational leaders will typically look towards what that social interaction can actually provide the organization.

West (2004) provides a comprehensive list of reasons for what organizations might expect when using teams. This list can be summarized into four categories of expected organizational outcomes, including a) increased ...