eBook - ePub

A Companion to Classical Receptions

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Classical Receptions

About this book

Examining the profusion of ways in which the arts, culture, and thought of Greece and Rome have been transmitted, interpreted, adapted and used, A Companion to Classical Receptions explores the impact of this phenomenon on both ancient and later societies.

- Provides a comprehensive introduction and overview of classical reception - the interpretation of classical art, culture, and thought in later centuries, and the fastest growing area in classics

- Brings together 34 essays by an international group of contributors focused on ancient and modern reception concepts and practices

- Combines close readings of key receptions with wider contextualization and discussion

- Explores the impact of Greek and Roman culture worldwide, including crucial new areas in Arabic literature, South African drama, the history of photography, and contemporary ethics

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Reception within Antiquity and Beyond

CHAPTER ONE

Reception and Tradition

Introduction

This chapter is concerned with the use of the term ‘tradition’ in studying the reception of classical antiquity. Tradition is a remarkably open and wide-ranging concept. Its core meaning of ‘passing on’ has relevance in numerous contexts, and as a result tradition has a role in a wide range of disciplines well beyond the arts.

Within Classics, tradition has had a particular history which centres on the concept of the ‘classical tradition’. Long before ‘reception’ gained the prominence that it has now, the classical tradition was discussed and popularized by books like Gilbert Murray’s The Classical Tradition in Poetry (Murray 1927) and Gilbert Highet’s The Classical Tradition (Highet 1949). Such work needs to be seen on the one hand in relation to contemporary thinking about tradition outside Classics: outstanding here are T.S. Eliot’s 1920 essay on ‘Tradition and the individual talent’ and Aby Warburg’s 1932 The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity (see Kennedy 1997: 40–2, and the preface to Warburg 1999). On the other hand, work on the ‘classical tradition’ represents a more or less explicit engagement with debates over how and why Classics fits into the modern world. These debates go back to the nineteenth century – witness the altercations between Friedrich Nietzsche and Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff in the 1870s, both classicists by training but with diametrically opposed viewpoints about the subject (Henrichs 1995) – and then gained fresh relevance after the crisis of World War One: Murray’s work on the classical tradition is not an isolated phenomenon in the post-war years (on Murray as responding to the war see West 1984: 209–33). Already a few years earlier, two high-profile volumes had appeared devoted to the ‘legacies’ of Greece and Rome, edited by Murray’s friend R.W. Livingstone (1921) and Cyril Bailey (1923) respectively, and a multi-volume series Our Debt to Greece and Rome was published in the US between 1922 and 1948 (cf. Schein, this volume, ch. 6).

Today, work on the classical tradition from the first half of the twentieth century leaves a mixed impression. Murray’s book in particular reads with hindsight as a blend of sensitive analysis that still continues to be suggestive and a now rather dated eulogy of what he regards as ‘classical’ poetry. A similar point could be made about the notion of a classical tradition as a whole. It remains a useful and indeed evocative term referring to the engagement with classical antiquity in later periods: note for instance the International Journal of the Classical Tradition and the Blackwell Companion to the Classical Tradition (Kallendorf 2007). At the same time, some scholars, anxious because of the connotations of conservatism and elitism that the classical tradition cannot always shed, avoid it altogether at the expense of the term ‘reception’. Especially in Britain, reception is sometimes thought to be the less problematic concept of the two.

In this chapter, we will not step into the debates over the classical tradition, nor will we focus on discussing ‘tradition’ in general. Rather, we want to pick up on areas of classical scholarship in which tradition has an established role – by which we mean areas where scholars have become accustomed to using the term ‘tradition’, partly for historically contingent reasons but partly also because it seemed appropriate and helpful to do so. Most famously, tradition is at the heart of Homeric studies, but books have been published in recent years also on, for example, the Epicurean tradition, ritual lament in the Greek tradition, the Augustinian tradition and the Anacreontic tradition. All these traditions are of course also cases of reception, usually of whole strings of reception. Tradition and reception tend to overlap, though the precise relationship between the two terms, and their implications in any given area of study, is not always easy to pin down. So what we will do in this chapter is take the two traditions of Homeric epic and Anacreontic lyric and discuss what they have to offer to the student of reception. The reason we devote the bulk of the chapter to case studies is that we want to reflect the way both the study of tradition and that of reception depends on its material. Like many critical terms, ‘tradition’ and ‘reception’ are most effective when they are tailored from case to case. This is not to say that there are no general points to be made, and we will indeed make some such points; but we believe that it is important to stress the variation in possible approaches to tradition and reception, both in practice and at a more abstract conceptual level.

Reception and the Anacreontic tradition

Our first case study in reception and tradition is taken from the early modern reception of the Greek lyric poet Anacreon (sixth/fifth century BCE). Anacreon’s output is only preserved in fragments, with few complete poems. What is preserved fully, however, is the Anacreontea, a collection of mostly anonymous poems inspired by Anacreon, written between the first century bce and the ninth century CE (text and translation of both Anacreon and the Anacreontea in Campbell 1988, discussion in Rosenmeyer 1992). When the Anacreontea were first printed, in 1554 by Henricus Stephanus (= Henri Estienne) in Paris, they were widely taken to be by Anacreonhimself, and spawned a rich reception history in most European languages, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Our example will be a poem of unknown date by Abraham Cowley (1618–1667), published among his 1656 Miscellanies as one of eight ‘Anacreontiques: or, Some Copies of Verses Translated Paraphrastically out of Anacreon’.

Drinking

The thirsty Earth soaks up the Rain,

And drinks, and gapes for drink again.

The Plants suck in the earth, and are

With constant drinking fresh and faire.

The Sea it self, which one would think

Should have but little need of Drink,

Drinks ten thousand Rivers up,

So fill’d that they oreflow the Cup.

The busie Sun (and one would guess

By’s drunken fiery face no less)

Drinks up the Sea, and, when’has don,

The Moon and Stars drink up the Sun.

They drink and dance by their own light,

They drink and revel all the night.

Nothing in Nature’s Sober found,

But an eternal Health goes round.

Fill up the Bowl, then, fill it high,

Fill all the Glasses there; for why

Should every creature drink but I,

Why, Man of Morals, tell me why?

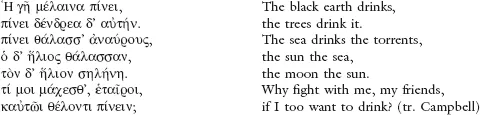

In analyzing this poem as an act of reception the first thing to point out is its close connection with one of the Anacreontea (21 in today’s standard numeration).

Clearly, Cowley’s poem uses the structure and conceits of the Anacreontea piece, expanding on it in length and level of rhetoric. Cowley imitates the basic sequence of the drinking earth, plants, sea, sun and moon, leading up to the question about the speaker’s own drink, but elaborates throughout and so produces a poem that is three times as long.

The next point to note is that Cowley’s poem (unlike his Greek source) is clearly tied to a particular political situation. It is one of a rash of English Anacreontic pieceswritten in the early to mid-seventeenth century by poets including Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, Alexander Brome and the Aeschylus editor Thomas Stanley. As Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians were gaining more and more political control their austere cultural and religious outlook was becoming increasingly dominant. Royalists found themselves beleaguered and many of them, including Cowley, spent some time in exile. It is in this context of Puritan supremacy that Cowley’s punchline about the ‘man of morals’ is to be understood. While the nameless Greek author just addresses his friends, Cowley makes a thinly veiled allusion to Puritans, perhaps even Oliver Cromwell himself, and their clampdown on drinking.

It is obvious that these socio-political connotations of the poem could be pursued in more detail (Revard 1991), but here we want to discuss three aspects of Cowley’s poem as part of the Anacreontic tradition more broadly.

1 Tradition as a chain of influence

One thing the Anacreontic tradition does for the student of Cowley is to bring into view a vast number of earlier Anacreontic poems, more or less directly relevant to Cowley’s own. Cowley’s ‘Drinking’ is linked with Anacreon through a long chain of what we might call intermediate acts of reception. Without doubt the most influential is the late antique and Byzantine Anacreontea collection, which itself constitutes a reception of Anacreon. The Anacreon of Cowley and his contemporaries was not the Anacreon printed in today’s editions but the Anacreontea. Most intermediate acts of reception are less momentous, of course, and do not reshape perceptions of an earlier text or author to the same degree. One such intermediate reception is a version of the same Anacreontea piece by the German poet Georg Rudolf Weckherlin, published in 1641 as ‘Ode oder Drincklied. Anacreontisch’ (Fischer 1884: 501–3). Like Cowley, and unlike most other poets writing versions of Anacreontea 21, Weckherlin expanded significantly on his model. The similarities in the detail of Cowley’s and Weckherlin’s expansion, together with the fact that Weckherlin spent time in England, have suggested to some scholars the dependency of one version on the other. Weckherlin may have drawn on Cowley, or Cowley on Weckherlin, alongside whatever other sources they used (Zeman 1972: 45–8; Revard 1991 traces other influences on Cowley).

Influence-spotting has sometimes acquired a bad name and can in fact be misleading. The complete set of literary influences (let alone cultural influences more broadly) that bear upon a poem is ultimately untraceable. In our example, even the role of Weckherlin is unclear. Moreover, we may ask which other Anacreontic poems Cowley was familiar with, and what drinking songs more broadly. What other poems may have shaped his habits? What anti-puritan jokes? We simply will never know what earlier material, consciously or unconsciously, went into Cowley’s poem, let alone what in turn had shaped that earlier material. We are able to point, in certain cases, to obvious influences, but those influences will always only be a few among many. That said, it is undeniable that Cowley’s creative act has behind it an enormous number of earlier creative acts. Even though we cannot delineate all or evenmost of them in an archaeology of influence, the influence of the past as such is undeniable. Anacreon is not transported onto Cowley’s desk or to Cowley’s period by a time machine (and the same is of course true for our reading of Anacreon or Cowley today). Renaissance or modern engagements with antiquity are shaped by many centuries of cumulative earlier engagements, starting in antiquity itself. Bearing in mind the wider Anacreontic tradition does not give us a key to tracing this build-up in exhaustive detail, but it shows us the importance of giving historical depth to any analysis of individual moments of reception, such as Cowley’s ‘Drinking’, and indeed to our own reading of Anacreon, Cowley or anything else.

2 Tradition as an imaginary context

The amorphous and elusive nature that the Anacreontic tradition shares with many other traditions is not just a hindrance but can also be an advantage. It offers poets a place of belonging. Homeric rhapsodes called themselves ‘sons of Homer’, making themselves part of a wider family (Graziosi, this volume, ch. 2). The Anacreontea collection does something comparable with Anacreon, whose name opens the first poem. The poets of the Anacreontea often remained anonymous, and in various ways positioned themselves as continuing a project started by Anacreon rather than advertising their own originality. Cowley is less self-effacing. He publishes in his own name and leaves his mark. Not least because of his rhetorical expansions, Cowley has often been regarded as the most important English Anacreontic poet (Baumann 1974: 73–9; Mason 1990: 107–9). The jibe at the ‘man of morals’, too, distinguishes this poem not just from Anacreontea 21, but also from other, less polemical, versions of it. Even so, Cowley can still be looked at as part of a larger project. He calls his piece a paraphrastic translation, and uses the term ‘Anacreontiques’ almost as the marker of a genre. He thus places his poem among other poems carrying this label, like Weckherlin’s ‘Ode oder Drincklied. Anacreontisch’ and like several of Herrick’s Hesperides (published 1648, see Braden 1978: 216–17). The ways individual authors place themselves in or against a tradition vary enormously. In most cases, like here, there is some blend of innovation, indeed flaunted innovation, and seamless integration.

Just as the nature of this blend varies so do its effects. In Cowley’s poem, one effect is a playful pretence of innocence. The piece poses as just an Anacreontic translation: there is nothing new. The fact that this mere translation is provocative in a context in which drink is a political issue would of course not have escaped Cowley’s readers. So the traditionality of Cowley’s stance sharpens rather than blunts the poem’s political edge.

But that is not the only effect it has. It would probably be wrong to see the avowedly Anacreontic aspect of the poem merely as mock-camouflage used for political attack. Even though Cowley is rarely harmless, this is probably the punchiest of his Anacreontiques, which suggests that Anacreon held further attractions for him. Arguably, he and his royalist friends also drew some comfort from communing with Anacreon and Anacreontically minded people of the past. As they had to keepthemselves to themselves, in a world that was hostile to their practices and beliefs, the Anacreontic tradition will have given them a more sympathetic imaginary home. They were not alone in enjoying drink and song.

3 Tradition as continuity

Much recent literary and cultural criticism focuses on what is particular about a given text or author. Why does Anacreon appeal to a royalist under the Protectorate? How does Cowley’s piece relate to Weckherlin’s? How does Cowley adapt Anacreontea 21? Not that these questions can be settled with certainty, but they can be discussed in interesting ways.

Thinking about the Anacreontic tradition gives a different vantage point. Of course, as we just pointed out, tradition too has room for particularity. Cowley created his own lastingly recognizable place within it. But tradition also puts a premium on continuity, sometimes even timelessness. Anacreontic poetry continued to be widely popular across a number of centuries. The appeal of each individual poem will have had something to do with its particular features and circumstances – such as Cowley’s anti-puritan snipe for the consumption of other anti-puritans – but for a balanced understanding of Anacreontic poetry one needs to come to terms also with the many features that one finds again and again, in different periods and languages: brevity (Cowley’s poem is at the long end of the spectrum); simplicity of metre (here: the iambic tetrameters); simplicity of language (Cowley is unusually rhetorical, but even Cowley’s language is quite straightforward); wit (here: the punch line); a small number of usually apolitical and unspecific themes (especially drink, which here has a political application, and love); and, above all, a light-hearted tone.

Perhaps one of the most helpful observations to make about these repeated features is to point out that many of them are shared with the ever-popular genre of drinking song, and to note that Anacreontic poetry weaves together refined poetry and banal forms of conviviality (Achilleos 2004). The connection with drinking song is important because it helps explain both the remarkable degree of stability in the tradition and its popularity in many contexts in which popular forms of song and high-cachet poetry could be brought together (Roth 2000 is particularly suggestive).

This is a rewarding but challenging line of enquiry to pursue further. What, one is led to ask, is it that gives drinking song and the way Anacreontic poetry uses it such wide appeal? Homeric criticism has learned to discuss formulae and types scenes, and the power that is locked up in them (see our second case study). In addition to providing convenient building blocks for composition in performance, such repeated material contains pieces of cultural memory in condensed form. Comparable models for thinking about other poetry are rare, even though the Anacreontic tradition like many other literary traditions is repetitive in its own way: repeated metrical patterns, repeated themes, repeated jokes, etc. The recent rise in the use of cognitive science in literary studies is promising here, and may eventually help analyze the traditional aspects of Anacreontic poems like Cowley’s. There is almost certainly something hardwired in the appeal of particular simple forms and particular the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Making Connections

- Part I: Reception within Antiquity and Beyond

- Part II: Transmission, Acculturation and Critique

- Part III: Translation

- Part IV: Theory and Practice

- Part V: Performing Arts

- Part VI: Film

- Part VII: Cultural Politics

- Part VIII: Changing Contexts

- Part IX: Reflection and Critique

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Companion to Classical Receptions by Lorna Hardwick, Christopher Stray, Lorna Hardwick,Christopher Stray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.