- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Screening Love and Sex in the Ancient World

About this book

This dynamic collection of essays by international film scholars and classicists addresses the provocative representation of sexuality in the ancient world on screen. A critical reader on approaches used to examine sexuality in classical settings, contributors use case studies from films and television series spanning from the 1920s to the present.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Screening Love and Sex in the Ancient World by Monica S. Cyrino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Screening Love and Sex in Ancient Myth and Literature

Chapter 1

G. W. Pabst’s Hesiodic Myth of Sex in Die Büchse der Pandora (1929)

Lorenzo F. Garcia Jr.

G. W. Pabst’s late silent era masterpiece depicts Louise Brooks as Lulu, a beautiful young woman whose unfettered sexuality leads to the ruin of those men and women who fall under her erotic sway.1 She is described as “Pandora” by the prosecutor at her husband’s murder trial and is condemned by the court, made an outlaw of the legal system in all its patriarchic glory. In critical work on Pabst’s film, many scholars have drawn a connection between Lulu and the Pandora of Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days2 to elucidate the film’s mythological background. Karin Littau (1995), Laura Mulvey (1996), and Maree Macmillan (2010) trace Lulu back to the mythological figure of Pandora to analyze how a figure associated with agricultural fertility—Pandora the “all giver”—becomes a femme fatale who takes men’s goods and in return provides only evils—Pandora the “all given.”3 The precise emphasis on fertility in the Pandora myth, however, has not been sufficiently read into Pabst’s film or Frank Wedekind’s earlier play Pandora’s Box, which Pabst drew on.

In this chapter I argue that Pabst and Wedekind’s misogynist visions of Lulu’s vibrant sexuality echo a tradition first stated in Hesiod’s poetry. According to Hesiod’s theory of sexual economy, later constitutive of Western concepts of gendered power relations, nonproductive female sexuality is depicted as pure expenditure without profit (Theogony 592–602). Only through productive sexual relations does the female body make a return on male investment of labor. Hesiod’s “Pandora” symbolizes both the destructive and the valuable potential of sexual relations, since Pandora is the source of both mortality itself—namely, labor, old age, disease, and death (Works and Days 42–48, 90–105)—and the unborn child “Hope” (Works and Days 93) that remains within her jar-like uterus. The demise of Pabst’s Lulu, then, signals a kind of patriarchal punishment of Lulu’s failure to be a productive investment instead of a wasteful expenditure.

Pabst and Wedekind: The Image of Lulu

G. W. Pabst’s screenplay (cowritten by Ladislaus Vajda) is based on the five-act “Monstertragedy” (Eine Monstretragödie) by Frank Wedekind, written between 1892 and 18954 but later divided into Erdgeist “Earth Spirit” (1895) and Die Büchse der Pandora “Pandora’s Box” (first published 1902, but continually revised under threat of censorship until 1913).5 Early performances of the plays featured Wedekind himself as Dr. Schön/Jack the Ripper and Tilly Newes, whom Wedekind would later wed, as Lulu.6 Pabst’s script recombines the two plays into a single work as Wedekind originally intended, but it condenses the plot at many points and expands at others. Lulu’s three marriages in Wedekind’s plays—to Dr. Goll, the painter Schwartz, and the newspaper editor Dr. Schön—are reduced to a single marriage in Pabst’s film, though that marriage is made paradigmatic so as to stand in for others.7 Pabst innovates at several points, such as the courtroom scene where Lulu is tried for Dr. Schön’s murder, a scene that does not appear in Wedekind’s plays.

Although Pabst’s Pandora’s Box is well known in cinema studies, it is less so for those who study classics, so I provide a brief plot summary. As the film begins, Lulu (Louise Brooks) is visited by Dr. Schön (Fritz Kortner), her lover and the editor of a widely distributed newspaper, because he wants to break off their relations so he can maintain public respectability and marry the daughter of an important government official (Daisy D’Ora). Lulu rejects the breakup; “You’ll have to kill me to get rid of me,” she says,8 and she seduces Schön beneath a painting of herself.

In the second act, Schön’s son, Alwa (Franz Lederer), is producing a dance revue with costumes designed by Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), “who is clearly represented as a woman defined by masculine features.”9 Alwa and Geschwitz look at sketches of costumed women; Lulu enters and insists Geschwitz design costumes for her; Alwa and Geschwitz gaze at her with desire.10 Schön and Alwa vie with one another over Lulu. Schön authorizes Alwa to include Lulu in his revue and promises his paper will make it a success. Father and son bond over the exchange of Lulu as sexual object and as image figured in Geschwitz’s drawings, and they part with Schön’s paternalistic advice: “Beware of that woman!”11

The third act takes place backstage at Alwa’s production. Schön attends the opening with his fiancée, and they both catch sight of Lulu; when Lulu spies Schön with his fiancée, she refuses to perform (“I’ll dance for the world, but not for that woman”).12 Instead, Lulu stages her own drama in which she seduces Schön in front of his fiancée and son. When the pair sees Lulu and Schön kissing, Lulu smiles at her victory and returns onstage.13 The act ends with Schön telling Alwa that he must now marry Lulu.

Schön marries Lulu only to find she i8s unfaithful to him, and his house and bedroom are filled with hidden lovers. Schön reestablishes his authority by the obvious phallic gesture of drawing a pistol to chase out would-be lovers, and then he tries to force Lulu to shoot herself, as he claims, “so that she does not make him a murderer as well.”14 In an ensuing struggle, Schön is shot and dies. Lulu is tried for Schön’s murder. The prosecutor’s argument explicitly compares Lulu to the mythological figure of Pandora: “Your honors, and gentlemen of the jury! The Greek gods created a woman—Pandora. She was beautiful and charming, and versed in the art of flattery … But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us … Counsel, you portray the accused as a persecuted innocent. I call her Pandora, for through her all evil was brought upon Dr. Schön! … The arguments of the defense counsel do not sway me in the least. I demand the death penalty!”15 Lulu is found guilty and flees from the law.

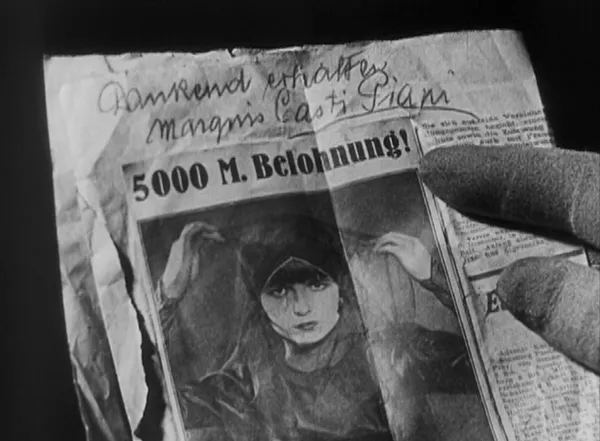

Driven by the consequences of her polyandry from respectable society to an illicit gambling boat somewhere in Paris, Lulu is blackmailed by men who know she is hiding from the police. In particular, Marquis Casti-Piani (Michael von Newlinsky) recognizes Lulu from a newspaper photograph; when he learns he can make more money by selling her into sexual slavery, he speaks with an Egyptian slaver, showing him photographs of Lulu in various costumes. Lulu escapes the gambling ship dressed in the outfit of a young sailor she has seduced, and she flees once again to the red-light district of London. In London she becomes a streetwalker to support herself, Alwa, and her pimp/father figure Schigolch (Carl Goetz); she is murdered on Christmas Eve in a violent encounter with a “John” who turns out to be Jack the Ripper (Gustav Diessl). Alwa meets Jack leaving Lulu’s ramshackle London flat, and the two men walk off separately into the foggy London night, “like men leaving the cinema … the sort of cinema that caters for men in raincoats.”16

Figure 1.1 A blackmail note written on a newspaper photograph of Lulu (Louise Brooks) in Die Büchse der Pandora (1929). Süd-Film.

The film revolves around Lulu and her relations with men, or in the case of the lesbian Geschwitz, a woman in a “masculine” relation to Lulu. The relationships between Lulu and her masculine others are specifically coded in terms of an exchange of money for visual pleasure.17 From the first shot of Lulu in the film—when Louise Brooks appears framed in an open doorway—Lulu is marked as “image.”18 As noted in the summary, Lulu appears everywhere as “image”: she seduces Schön beneath a painting of herself; Geschwitz, Alwa, and Schön exchange sketches of her in costume; Casti-Piani recognizes her from a photograph and later barters with a slave-trafficker over photos of her. Lulu’s image captivates: throughout the film Brooks is shot in soft-focus, softly lit close-ups, lifted from the background and set in an imaginary space of pure fantasy.19 Her body is shiny: skin, eyes, teeth, hair, and costume are highlighted with soft backlighting, essentially fetishized by tricks of illumination.20 Schön’s name implies a “would-be Renaissance aesthete,” and the artwork throughout his home betrays his attraction to images.21 Lulu is captivated by her own image, especially when she gazes at herself in a large mirror as she takes off her wedding gown.22 In Wedekind’s play, Lulu and Alwa speak about her reflection:

Lulu: Looking at myself in the mirror I wished I were a man … my own husband.

Alwa: You envy your husband the happiness you offer him.23

Even in death, Lulu remains image: in an extreme close-up as she sits on Jack’s lap, Lulu’s face appears like a waning moon;24 the glow of her face is matched only by that of the knife on the table as Jack surveys her body.

At a key moment in Pabst’s film, Lulu’s trial, a scene wholly invented by Pabst, Lulu is once more rendered an image. A defendant dressed all in black, Lulu is the negative image of the veiled bride she played in the preceding scene. She is gazed on by judges, news reporters, and a full spectator galley. Photographers snap pictures; artists sketch her. All the while, the prosecutor glares at her, wearing a monocle that recalls Schön’s eye-piece: this is the paternalistic gaze that condemns Lulu.25 It is at this very moment that she is identified with “Pandora.”

Pandora is the protofemale of Greek thought, created for men by the gods.26 The economy of the image is a trope particularly at home in the mythopoetic tradition of Pandora, as I detail in the next section. The iconic dimension of Pandora has been well noted in scholarship on Pabst’s film. What has been less noted is a secondary economy underlying both mythological accounts of Pandora and Lulu: labor and (re)productivity.

Hesiod’s Pandora: Exchange, Agricultural Labor, and Sexual (Re)production

In the Theogony and Works and Days, Hesiod associates the creation of the first woman, Pandora, with mankind’s mortality and need to work for sustenance. In Hesiod’s works Pandora is created by the craft-god Hephaestus as a punishment for Prometheus’s transgressions against the gods on mankind’s behalf: Prometheus first deceives Zeus with an unfair distribution of sacrificial offerings (Theogony 535–60; Works and Days 47–48) and then steals fire from the gods to give to men (Theogony 561–69; Works and Days 50–52).27

Pandora appears in the context of exchange, both the sacrifice offered to the gods and the price Zeus demands for fire, that marks a fundamental separation between mankind and the gods; Pandora’s advent signals the rupture between men and gods.28 According to the logic of Hesiod’s account, then, before Pandora men lived without labor, disease, and old age (Works and Days 90–93):29

For before this, the races of men used to live on earth

far away and apart from evils and apart from hard toil

and painful diseases, which gave death to men.

A wretched life ages men before their time.

In this prelapsarian vision of human life before Pandora and the need for sexual reproduction,30 the earth once produced of its own accord, without need for human labor (Works and Days 112–18):

They [= men] used to live like gods, with a carefree heart,

far away and apart from toil and misery. Nor at all was wretched

old age upon them, but always the same with respect to their feet and hands

they took pleasure in feasts, outside of all evils.

They died as if overcome by sleep. All good things

were available for them. The life-giving plow land bore fruit

of its own accord—a great deal of it, unstintingly.

Hesiod imagines men living like gods before the anger of Zeus and the advent of Pandora: their “carefree” life is described in terms of distance from “evils” (113, 115): care, toil, misery, old age. The earth was exuberantly fertile without added labor; man had only to gather and eat what the earth produced of its own accord (118). Now, however, the procurement of grain requires agricultural labor: the earth must...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Screening Love and Sex in the Ancient World

- Part 1: Screening Love and Sex in Ancient Myth and Literature

- Part 2: Screening Love and Sex in Ancient History

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors