eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications

About this book

Over the last decade, political economy has grown rapidly as a specialist area of research and teaching within communications and media studies and is now established as a core element in university programmes around the world. The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications offers students and scholars a comprehensive, authoritative, up-to-date and accessible overview of key areas and debates.

- Combines overviews of core ideas with new case study materials and the best of contemporary theorization and research

- Written many of the best known authors in the field

- Includes an international line-up of contributors, drawn from the key markets of North and Latin America, Europe, Australasia, and the Far East

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Political Economy of Communications by Janet Wasko, Graham Murdock, Helena Sousa, Janet Wasko,Graham Murdock,Helena Sousa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Legacies and Debates

1

Political Economies as Moral Economies

Commodities, Gifts, and Public Goods

Goods and the Good Life

Economics, as it emerged as an academic discipline at the turn of the twentieth century, claimed to offer a scientific basis for the study of economic affairs. Its dominant form presented capitalism as a network of markets, regulated by rational self-interest, whose organization and outcomes could be modeled mathematically. Empirical inquiry was fenced off from questions of value, cutting the links to moral philosophy that had been central to the project of political economy launched in the late eighteenth century as part of a more general search for a secular basis for moral action. The catastrophic financial crash set in motion by the collapse of the Lehman Brothers bank in September 2008 has now forced questions of ethics back into discussions of economic affairs in the most brutal way.

This “moral turn” is particularly marked in Britain where, for over a decade, the City of London has been uncritically celebrated as one of the key hubs of the new capitalism and left to compete in the global marketplace with the minimum of oversight. The social and human costs are now being counted in rising unemployment, decimated retirement savings, and savage cuts in public provision as funding for essential services is diverted to pay for the unprecedented scale of government borrowing required to bail out failing banks. Despite the havoc visited on countless working lives, many bankers have continued to display a callous disregard for public misery and to pay themselves huge bonuses. Faced with this selfishness and self-regard several notable celebrants at the altar of finance have been moved to recant, or to voice major doubts about their former faith. Stephen Green, the Group Chairman of HSBC, one of the world’s largest banks, has been moved to argue that “capitalism for the 21st century needs a fundamentally renewed morality to underpin it,” one that asks again “what progress really is. Is it the accumulation of wealth, or does it relate to a broader, more integrated understanding of well-being and quality of life” (Green 2009, 35). Gordon Brown, who as Chancellor, and then Prime Minister, presided over a radically deregulated financial sector, belatedly concludes that “we have discovered to our cost, without values to guide them, free markets reduce all relationships to transactions [and] unbridled and untrammelled, become the enemy of the good society” (Brown 2010).

This admission would have come as no surprise to Adam Smith, born like Brown, in the town of Kirkaldy in Scotland, and one of the founding figures in developing a political economy of complex societies. From the outset, political economists saw questions about how the production and circulation of goods should be organized as part of a more general philosophical inquiry into the constitution of the good society. Smith’s promotion by neoliberals as a militant apostle of free markets conveniently elides the strong moral basis of his thought. His lectures as Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University were the basis for his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), in which he famously argues that although the rich may only be interested in “the gratification of their own vain and insatiable desires … They are led by an invisible hand,” which without them intending it or knowing it leads them to “advance the interest of the society” by dividing “with the poor the produce of all their improvements” (Smith 1969, 264–5). This, as the radical political economist Joan Robinson tartly noted, was the “ideology to end ideologies” (Robinson 2006, 76), an act of intellectual alchemy that turned the base metal of self-interest into the gold of social equity. By assuming that accumulation always produced benign outcomes, it abolished exploitation with the stroke of a pen. But as Smith acknowledged elsewhere in the text, while commercial calculation provided a practical basis for social order, it did not produce the good society. This required generosity and mutuality. Societies, he argued, “may be upheld by a mercenary exchange of good offices according to an agreed valuation,” but “not in the most comfortable state” (Smith 1969, 125). For Smith: “All members of society stand in need of each other’s assistance [and] where [this] is reciprocally afforded from love, from gratitude, from friendship and esteem, the society flourishes and is happy [and] all the different members of it … are, as it were, drawn to one common centre of mutual good offices” (p. 124).

In Smith’s view, however, since egotism was a stronger motivating force than altruism, the spirit of beneficence and reciprocity could not be relied on to take the weight of a complex society. It was “the ornament which embellishes, not the foundation which supports the building” (p. 125). Order required an effective justice system to punish wrongdoers.

Putting the “Political” into Political Economy

In 1776 Smith published his second major work, The Wealth of Nations. Within months of its appearance, the American Declaration of Independence accelerated the struggle for full popular participation in the process of government. The American and French Revolutions announced the death of the subject and the birth of the citizen. People were no longer to be subjected to the unaccountable power of monarchs, emperors, and despots. They were to be autonomous political actors, with full and equal rights to participate in social life and in the political decisions affecting their lives. From that point on, the terms of debate changed irrevocably. Discussion about how best to respond to the expansion of capitalism, and its transition from a mercantile to an industrial base, was bound up with debates on the constitution of citizenship and the state’s role in guaranteeing the concrete resources that supported full participation. Analysis of the economic order could not be separated from considerations of extended state intervention, its nature, rationale, and limits. Questions of political economy were more than ever questions about the political.

Smith saw a clear role for the state in addressing market limits, arguing that: “When the institutions or public works which are beneficial to the whole society … are not maintained by the contribution of such particular members of the society as are most immediately benefitted by them, the deficiency must in most cases be made up by the general contribution of the whole society” (Smith 1999, 406).

Which institutions qualified for public subsidy, however, became a focus for heated argument. Smith himself was cautious. He saw a role for public money in supporting universal basic education, but argued that the state could best support general cultural life, “painting, music … dramatic representations and exhibitions” by “giving entire liberty to all those who for their own interest” would provide them (1999, 384). As the struggle for full citizenship escalated, however, increasing doubts were raised over the market’s ability to guarantee cultural rights.

It was clear that some of the essential resources required for full participation – minimum wages, pensions, unemployment and disability benefits, holiday entitlements, housing, and healthcare – were material and these became the site of bitter struggles over the terms and scope of collective welfare. But it was equally clear that they were not enough in themselves. They had to be matched by essential cultural resources; access to comprehensive and accurate information on contemporary events and to the full range of opinions they have generated; access to knowledge, to the frameworks of analysis and interpretation that place events in context, trace their roots, and evaluate their consequences; the right to have one’s life and ambitions represented without stereotyping or denigration; and opportunities to participate in constructing public images and accounts and contribute to public debates (Murdock 1999).

Delivering these resources on an equitable basis shifted the state from a minimalist to a more expansive role. As well as deterring crime and guaranteeing the orderly social and financial environment required for commercial transactions, it was increasingly expected to deliver on the promise of citizenship. As part of this process, the management of cultural provision and mass communication, pursued through varying combinations of regulation and subsidy, became very much part of public policy. Regulation aimed to ensure that the public interest was not entirely subordinated to the private interests of media owners and advertisers. Subsidy addressed the market’s perceived failure to deliver the full range of cultural rights by financing cultural institutions organized around the ideal of “public service” rather than profit generation.

These initiatives constructed a dual cultural and communications system. On the one side stood a dominant commercial sector, either selling cultural commodities (books, magazines, cinema tickets, hit records) directly to consumers or selling audience attention to advertisers and offering the product (commercial radio and television programming) free. On the other side stood a less well-resourced public sector providing a range of public cultural goods and services: libraries, museums, galleries, public broadcasting organizations. This was the landscape that the political economy of communications in western capitalism encountered when it emerged as a specialized field of academic study after World War II.

It produced a preoccupation with capital–state relations that spoke to the shifting organization of capitalism at the time. The project of reconstruction in Europe produced varying forms of welfare capitalism in which the state took on an increasing range of responsibilities for cultural and communications provision. Decolonization struggles created a proliferating number of newly independent states, many of which opted for “development” strategies that relied on concerted state intervention in major sectors, including culture and communications. The global ascendency of American capitalism and the growing power and reach of the media majors raised pressing questions of regulation at home and cultural imperialism abroad. As centrally planned economies with no legal countervailing private sector, the two major communist blocs, controlled by the Soviet Union and China, remained largely outside this debate, however. Consequently, though they were of intense interest to political scientists, they were largely ignored by political economists of communication.

This landscape changed again in the late 1970s, as the balance between capital and state shifted decisively in favor of capital. The collapse of the Soviet Union, Deng’s turn to the market in China in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, and India’s break with Gandhi’s ethos of self-sufficiency, reconnected three major economic regions to the circuits of global capitalism after decades of isolation or relative distance. At the same time, concerted neoliberal attacks on the inefficiency and unresponsiveness of the public sector ushered in an aggressive process of marketization in a number of emerging and established economies, including Britain (Murdock and Wasko 2007). Against this background, it is not surprising that critical political economists of communication have given priority to challenging the key tenets of “market fundamentalism” and defending public sector institutions.

This binary mindset abolishes almost entirely any sustained consideration of the economy of gifts and the many ways that mutual assistance and reciprocity have been expressed in a variety of practical forms throughout the history of modern capitalism. Gifting is the central organizing principle of civil society. Whenever people mobilize spontaneously to protect or pursue their shared interests, we see labor given or exchanged voluntarily with no expectation of monetary payment. “Civil society is where we express ‘we’ rather than just ‘me’, where we act with others rather than only doing things for them or to them” (Carnegie UK Trust 2010, 148). With the rise of the Internet, and the proliferating range of collaborative activities it supports, this neglected economy has been rediscovered and its “most radical parts … from the open source movement and creative commons to the activists innovating around social networks” hailed as a new basis for civil society (p. 148). Unfortunately, rather than seeing it as a necessary third term, its most ardent enthusiasts have constructed another binary opposition in which online social sharing is locked in an escalating battle with corporations intent on extending their reach by commandeering unpaid creative labor and developing new revenue streams. This struggle is real enough, but it is not the whole story. It omits the ways that the expansion of the Internet has also revivified public cultural institutions.

Competing Moral Economies

Whenever we engage in transactions involving the consumption or exchange of goods and services, we enter a chain of social relations stretched over time. Looking backward poses questions about the conditions of production and the social and environmental costs incurred, forcing considerations of justice and equity to the forefront of debate. Looking forward raises issues of waste, disposability, sustainability, and shared fate. These concerns are underpinned by fundamental questions about our responsibilities and obligations toward all those people who we will never meet but whose life chances and opportunities for self-realization are affected by the modes of production and forms of exchange we choose to enter into. This is the central moral question facing modern societies, but it immediately bumps up against the militant promotion of the ethos of possessive individualism that underpins capitalism.

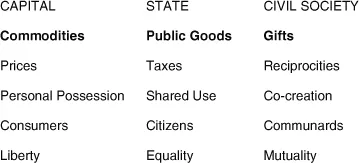

If we trace the fate of the demands for liberty, equality, and fraternity announced by the French Revolution, we see the rhetoric of individual freedom annexed by the champions of the minimal state and the “consumer society,” equality transmuted into the chance to enter structurally unequal contests for personal advancement, and mutuality as a sadly diminished third term. As Richard Titmuss reminds us, capitalism constantly prompts us to ask: “Why should men not contract out of the ‘social’ and act to their own immediate advantage? Why give to strangers? – a question provoking an even more fundamental moral issue: who is my stranger in relatively affluent, acquisitive and divisive societies …? What are the connections if obligations are extended?” (Titmuss 1970, 58). How we answer, or sidestep, this central moral question will vary depending on the nature of the transactions we engage in. Each of the three main ways of organizing exchange relations in contemporary societies – commodities, public goods, and gifts – invites us to assume a particular identity, to balance private interests against the public good in particular ways, and to recognize or deny our responsibilities to strangers. These three political economies are therefore also moral economies. Figure 1.1 sketches out the main differences between them. In the rest of this chapter I want to elaborate on these contrasts, to explore their consequences for the organization of culture and communications, and to examine how the relations between them are shifting in the emerging digital environment.

Figure 1.1 Contested moral economies

Commodities: Possessions, and Dispossessions

A commodity is any good or service that is sold for a price in the market. A range of economic systems contain elements of commodity exchange. Command economies have “black” markets in scarce goods. In colonial societies, commodities have coexisted with barter and gift exchange. But only in a fully developed capitalist system is the production and marketing of commodities the central driving force of growth and profit. Writing in 1847, observing the social order being reshaped in the interests of industrial capital, Marx was in no doubt that the process of commodification, which sought to convert everything into an article for sale, was at the heart of this process. He saw the new capitalism ushering in “a time in which even the things which until then had been communicated, but never exchanged, given but never sold, acquired but never bought – virtue, love, conscience – all at last enter into commerce – the time where everything moral or physical having become a saleable commodity is conveyed to the market” (Marx 2008, 86–7).

A number of commentators have seen the onwards march of commodification as a generalized form of enclosure extended to more and more kinds of resources (see Murdock 2001). The first enclosure movement began in Tudor times when agricultural entrepreneurs fenced off land previously held in common for villagers to graze sheep and collect firewood and wild foods, and incorporated it into their private estates. It is a useful metaphor because it highlights the fact that capitalist accumulation always entails dispossession (see Harvey 2005, 137–82).

By stripping villagers of access to many of the resources that had enabled them to be mostly self-sufficient, the original enclosure movement forced them to become agricultural workers for hire, selling their labor for a wage. Then, as they moved to the new industrial cities, their vernacular knowledge and skills in building, self-medication, growing and preserving foods, gradually atrophied as they were beckoned to enter the new consumer system in which the powers of self-determination taken away by the industrial labor process were returned in leisure time as the sovereign right to choose between competing commodities. Against a backdrop where routine industrial and clerical work was repetitive and alienating, and offered little intrinsic satisfaction or opportunity for self-expression, it was essentia...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Editor's Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Political Economy of Communications

- Part I Legacies and Debates

- Part II Modalities of Power

- Part III Conditions of Creativity

- Part IV Dynamics of Consumption

- Part V Emerging Issues and Directions

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- Wiley End User License Agreement