![]()

1

WINNING THE BRAND RELEVANCE BATTLE

First they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. Then they fight you. Then you win.

—Mahatma Gandhi

Don’t manage, lead.

—Jack Welch, former GE CEO and management guru

Brand relevance has the potential to both drive and explain market dynamics, the emergence and fading of categories and subcategories and the associated fortunes of brands connected to them. Brands that can create and manage new categories or subcategories making competitors irrelevant will prosper while others will be mired in debilitating marketplace battles or will be losing relevance and market position. The story of the Japanese beer industry and the U.S. computer industry illustrate.

The Japanese Beer Industry

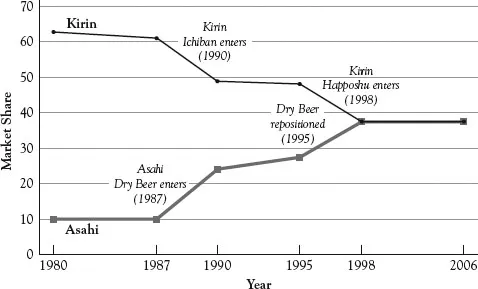

For three and a half decades the Japanese beer market was hypercompetitive, with endless entries of new products (on the order of four to ten per year) and aggressive advertising, packaging innovations, and promotions. Yet the market share trajectory of the two major competitors during these thirty-five years changed only four times—three instigated by the introduction of new subcategories and the fourth by the repositioning of a subcategory. Brands driving the emergence or repositioning of the subcategories gained relevance and market position, whereas the other brands not relevant to the new subcategories lost position—a remarkable commentary on what drives market dynamics.

Kirin and Asahi were the main players during this time. Kirin, the dominant brand from 1970 to 1986 with an unshakable 60 percent share, was the “beer of beer lovers” and closely associated with the rich, somewhat bitter taste of pasteurized lager beer. A remarkable run. There were no offerings that spawned new subcategories to disturb.

Asahi Super Dry Appears

Asahi, which in 1986 had a declining share that had sunk below 10 percent, introduced in early 1987 Asahi Super Dry, a sharper, more refreshing beer with less aftertaste. The new product, which contained more alcohol and less sugar than lager beers and had special yeast, appealed to a new, younger generation of beer drinkers. Its appeal was due in part to a carefully crafted Western image supported by its label (see Figure 1.1), endorsers, and advertising. Both the product and the image were in sharp contrast to Kirin.

In just a few years, dry beer captured over 25 percent of the market. In contrast, it took light beer eighteen years to gain 25 percent of the U.S. market. It was a phenomenon of which Asahi Super Dry, perceived to be the authentic dry beer, was the beneficiary. In 1988 Asahi’s share doubled to over 20 percent and Kirin’s fell to 50 percent. During the ensuing twelve years Asahi continued to build on its position in the dry beer category, and in 2001 it passed Kirin and became the number-one brand in Japan with a 37 percent share, a remarkable result. Think of Coors passing Anheuser-Busch, a firm with a long-term market dominance similar to the one Kirin enjoyed.

It is no accident that Asahi was the firm that upset the market. In 1985 Asahi had an aggressive CEO who above all wanted to change the status quo, both internally and externally. Toward that end he changed the organizational structure and culture to encourage innovation. Of course, he was “blessed” with financial and market crises. Kirin, however, had an organization entirely focused on maintaining the current momentum and on doing exactly what they had always done.

Kirin responded in 1988 with Kirin Draft Dry beer but, after having touted Kirin lager beer for decades, lacked credibility in the new space. Further, the ensuing “dry wars,” in which Asahi forced Kirin to make changes to its packaging to reduce the similarity of Kirin Draft Dry to the Asahi product, reinforced the fact that Asahi was the authentic dry beer. Kirin, whose heart was never in making a beer that would compete with its golden goose with its rich tradition and many loyal buyers, was perceived by many as the bully trying to squash the feisty upstart. Over the ensuing years, a bewildering number of efforts by Kirin and the other beer firms to put a dent in the Asahi advance were unsuccessful.

Kirin Ichiban Arrives

The one exception to efforts to create new subcategories with new beer variants was Kirin Ichiban, introduced in 1990, made from a new and expensive process involving more malt; filtering at low temperature; and, most important, using only the “first press” product. Its taste was milder and smoother than Kirin Lager’s, with no bitter aftertaste. Competitors were stymied by the cost of the process, the power of the Kirin Ichiban brand, and the distribution clout of Kirin. Kirin Ichiban caused a pause in the decline of the Kirin market share that lasted from 1990 to 1995. Its role in the Kirin portfolio steadily grew until, in 2005, it actually sold more than Kirin Lager—although the combination of the two was then far behind Asahi Super Dry.

Dry Subcategory is Reenergized

In 1994 Asahi, by this time the only dry beer brand, developed a powerful subcategory positioning strategy around both freshness and being the number-one draft beer with a global presence. While Asahi was enhancing the dry subcategory, Kirin was simultaneously damaging the lager subcategory. Perhaps irritated by Asahi’s number-one-draft-beer claim, Kirin converted to a draft beer making process and changed Kirin Lager to Kirin Lager Draft (the original still was on the market as Kirin Lager Classic but was relegated to a small niche). Kirin tried to make Kirin Lager Draft more appealing to a younger audience, but instead its image became confused, and its core customer base was disaffected. As a result, from 1995 to 1998 the subcategory battle between dry and lager resulted in Asahi Super Dry extending its market share eight points to just over 35 percent, while Kirin was falling nine points to around 39 percent.

Happoshu Enters

In 1998 a new subcategory labeled happoshu, a “beer” that contained a low level of malt and thus qualified for a significantly lower tax rate, got traction when Kirin entered with its Kirin Tanrei brand (Suntory introduced the first happoshu beer in 1996 but lost its position to Tanrei). By early 2001, after this new subcategory had garnered around 18 percent of the beer market, Asahi finally entered, but could not dislodge Kirin. The Asahi entry had a decided taste disadvantage, in large part because Kirin Tanrei had a sharper taste that was reminiscent of Asahi Super Dry. Asahi wanted no such similarity for its happoshu entry because of the resulting potential damage to Asahi Super Dry.

By 2005 Kirin had taken leadership in both the happoshu subcategory and in another subcategory, a no-malt beverage termed “the third beer,” which had an even greater tax advantage. From 2005 on, these two new subcategories captured over 40 percent of the Japanese beer market. In 2009 the two Kirin entries did well, with over three times the sales of the Asahi entries, and actually outsold the sum of Kirin Lager and Kirin Ichiban sales by 50 percent. As a result, Kirin recaptured market share leadership in the total beer category including happoshu and the third beer, albeit by a small amount, despite the fact that Asahi had nearly a two-to-one lead in the conventional beer category.

The changes in what people buy and in category and subcategory dynamics are often what drive markets. Figure 1.2 clearly shows the four times the market share trajectory in the Japanese beer market changed—all driven by subcategory dynamics. Brands that are relevant to the new or redefined category or subcategory, such as Asahi Super Dry in 1986 or Kirin Ichiban in 1990 or Kirin Tanrei in 1998, will be the winners. And brands that lose relevance because they lack some value proposition or are simply focused on the wrong subcategory will lose. That can happen insidiously to the dominant, successful brands, as with Kirin Lager in the mid-1980s and Asahi in the late 1990s.

Note the importance of brands in the ability of firms to affect category and subcategory position. Kirin Lager captured the essence of lager and the Kirin heritage. Asahi Super Dry defined and represented the new dry subcategory, even when Kirin Draft Dry was introduced. Kirin Tanrei was the prime representative of the happoshu category. And the repositioning of Asahi Super Dry really repositioned the dry subcategory, because at that point Asahi was the only viable entry.

The U.S. Computer Industry

Consider also the dynamics of the U.S. computer industry during the last half century and how these dynamics affected the winners and losers in the marketplace. The story starts in the 1960s when seven manufacturers, all backed by big firms, competed for a place in the mainframe space. However, as “computers as hardware” suppliers they became irrelevant in the face of IBM, who defined its offering as a problem-relevant systems solution supplier and thus created a subcategory. Then came the minicomputer subcategory in the early 1970s, led by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Data General, and HP, in which a computer served a set of terminals and in which the mainframe brands were not relevant.

The minicomputer business itself became irrelevant with the advent of servers and personal computers as hardware, and Data General and DEC faded while HP adapted by moving into other subcategories. Ken Olsen, the DEC founder and CEO, has famously been quoted as saying in 1977, “There is no reason why any individual would want a computer in his home.” Although the quote was taken out of context, the point that emerging subcategories, in this case the personal computer (PC) subcategory, are often underestimated is a good one.1

The PC subcategory itself fragmented into several new subcategories driven by very different firms. IBM was the early dominant brand in the PC subcategory, bringing trust and reliability. Dell defined and led a subcategory based on building to order with up-to-date technology and direct-to-customer sales and service. A portable or luggable niche was carved out of the personal computer segment, initially by Osborne in 1981 with a twenty-four-pound monster and ultimately in 1983 by Compaq, who became the early market leader. Then came the laptop, which was truly portable. Toshiba led this subcategory at first, until the IBM ThinkPad took over the leadership position with an attractive design and clever features.

Sun Microsystems led in the network workstation market, and SGI (Silican Graphics) led in the graphic workstation market, both involving heavy-duty, single-user computers. The workstation market evolved into the server subcategory. Sun was a dominant server brand in the late 1990s for Internet applications, but fell back as the Internet bubble burst.

In 1984 Apple launched the Macintosh (Mac), creating a new subcategory of computers. It was revolutionary because it changed the interaction of a user with a computer by introducing new tools, a new vocabulary, and a graphical user interface. There was a “desktop” with intuitive icons, a mouse that changed communication with a computer, a toolbox, windows to keep track of applications, a drawing program, a font manager, and on and on. And it was in a distinctively designed cabinet under the Apple brand. In the words of the Mac’s father, Steve Jobs, it was “insanely great.”2 The 1984 ad in which a young women in bright red shorts flings a sledgehammer into a screen where “big brother” (representing of course IBM) spouts out an ideology of sameness was one of the most notable ads of modern times. For the next decade and more there were core Mac users, especially among the creative community, who were passionately loyal to the Mac and enjoyed visible, self-expressive benefits from buying and using the brand. It took six years for Microsoft to come up with anything comparable.

In 1997 Steve Jobs, returning from a forced twelve-year exile from Apple, was the driving force behind the iMac (“i” initially represented “Internet enabled” but came to mean simply “Apple”). The iMac provided a new chapter to the Mac saga and became a new—or at least a revised—subcategory. The best-selling computer ever, its design and coloring were eye-catching. Incorporating the then-novel use of the USB port, Apple made the remarkable decision to omit a floppy disk. Instead of dooming the product as many predicted, this made the product appear advanced—made for an age in which people would share files over the Internet instead of via disks.

Another computer revolution is under way. Products such as smart phones and tablets like iPad are replacing laptop and even desktop computers for many applications. The new winners are firms such as Apple, Google with its Android software, the communication firms AT&T and Verizon, server farms, and application entrepreneurs. The losers will be the conventional computer hardware and software businesses.

As in the case of Japanese beer, it was the emergence of new subcategories such as solutions-focused mainframes, minicomputers, workstations, servers, PCs, Macintosh, portables, laptops, notebooks, and tablets that create the market dynamics that changed the fortunes of the participates. Again and again competitors fell back or disappeared, and new ones emerged as new subcategories were formed. The ongoing marketing efforts involving advertising, trade shows, and promotions had little impact on the market dynamics. A similar analysis could be made concerning most industries.

Brand relevance is a powerful concept. Understanding and managing relevance can be the difference between winning by becoming isolated from competitors or being mired in a difficult market environment where differentiation is hard to achieve and often short-lived. It is not easy, however, but requires a new mind-set that is sensitive to market signals, is forward looking, and values innovation.

This chapter starts by defining and comparing the two perspectives of the marketplace, the brand preference model and the brand relevance model. It then describes the central concept of creating a new category or subcategory and the role of substantial and transformational innovation in that process. The next section describes the new management task, to influence and manage the perceptions and position of the new category and subcategory. The chapter then turns to the potential power of the first mover advantage and the value of being a trend driver. The payoff of creating new categories and subcategories is then detailed and followed by a description of the four tasks that are necessary to create a new category or subcategory. Finally, the brand relevance concept is contrasted with approaches put forth by other authors toward a similar objective and the rest of the book is outlined.

Gaining Brand Preference

There are two ways to compete in existing markets—gaining brand preference and making competitors irrelevant.

The first and most commonly used route to winning customers and sales focuses on generating brand preference among the brand choices considered by customers, on beating the competition. Most marketing strategists perceive themselves to be engaged in a brand preference battle. A consumer decides to buy an established product category or subcategory, such as SUVs. Several brands have the visibility and credibility to be considered—perhaps Lexus, BMW, and Cadillac. A brand, perhaps Cadillac, is then selected. Winning involves making sure the customer prefers Cadillac to Lexus and BMW. This means that Cadillac has to be more visible, credible, and attractive in the SUV space than are Lexus and BMW.

The brand preference model dictates the objectives and strategy of the firm. Create offerings and marketing programs that will earn the approval and loyalty of customers who are buying the established category or subcategory, such as SUVs. Be preferred over the competitors’ brands that are in that category or subcategory, which in turn means being superior in at least one of the dimensions defining the category or subcategory and being at least as good as competitors in the rest. The relevant market consists of those who will buy the established category or subcategory, and market share with respect to that target market is a primary measure of success.

The strategy is to engage in incremental innovation to make the brand ever more attractive or reliable, the offering less co...