![]()

Part One: Fundamentals

1

Introduction to Food Microbiology

Martin Adams

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The microbial world is defined by its size – organisms that generally have microscopic dimensions attract the interest of microbiologists. One consequence of this is that the birth of microbiology coincides with the advent of the microscope, which enabled us to see microorganisms for the first time. It is particularly associated with the work of Robert Hooke, who described the fruiting bodies of the mould Mucor on leather in 1665, and of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who saw bacteria while examining pepper-water infusions in 1676 (Bardell 1982; Gest 2009).

Despite these early observations, it was not until the nineteenth century and the work of luminaries such as Pasteur and Koch that microbiology can be truly said to have taken off as a scientific discipline. Like many who followed them, the interest of these pioneers was focused primarily on what microorganisms do rather than what they are. As a result, the struggle against infectious disease understandably looms large in any history of the subject. However, food microbiology, which studies the ways in which microbial activity associated with foods impinges on humankind, also has considerable practical and economic importance and was not entirely ignored. Pasteur (Debré 1994), for example, worked extensively on fermented food products such as wine, beer and vinegar, elucidating how deviations from the usual fermentation pattern can produce disorders in the product.

Currently the most fundamental division of the living world is into three domains based on differences in cell type: the Bacteria, the Archaea and the Eukarya. There are microorganisms of interest to food microbiologists in each of these domains. Members of the Bacteria naturally predominate but in the Eukarya, the fungi (yeasts and moulds) are extremely important in a number of areas such as food fermentations, spoilage and mycotoxins. The Archaea are of little significance in food other than in some very specific situations such as extreme halophilic bacteria that can sometimes spoil heavily salted products and may play a role in the manufacture of products such as the fish sauces of Southeast Asia. Some basic features of the different groups of cellular microorganisms are described in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Cellular microorganisms and their basic features.

|

| Bacteria | Single-celled organisms. Prokaryotes, i.e. they lack a nuclear membrane surrounding their DNA

Cells: - are enclosed by a cell wall containing the polymer peptidoglycan

- are generally spherical (coccus), rod-shaped (bacillus), spiral or curved

- are normally reproduced by binary fission where one cell splits into two indistinguishable daughter cells

- may form chains or clumps

- are sometimes motile by means of flagella

| Different bacteria can be responsible for spoilage, foodborne illness and food fermentation processes |

| Eukaryotes | Eukaryotic, i.e. possess a distinct nucleus enclosed by a nuclear membrane and containing their DNA

Fungi have cell walls containing the polymer chitin and include the moulds and yeasts. The moulds are multicellular organisms. They grow as filaments called hyphae which grow, spread and branch to form a visible mass known as mycelium. Can produce characteristic structures associated with spore production and dispersal

Yeasts are unicellular fungi and are generally spherical or oval cells, larger than bacteria that multiply by budding off daughter cells and sometimes by fission

Protozoa are unicellular, eukaryotes | Some moulds produce toxic secondary metabolites known as mycotoxins

Moulds and yeasts are both important in the production of a wide range of fermented foods

Some pathogenic protozoa can be transmitted by foods |

| Archaea | Prokaryotic cells (see above). Where they possess cell walls peptidoglycan is absent

Often found in extreme environments, e.g. extreme halophiles in very salty conditions | Do not cause disease in humans

May be responsible for spoilage of some high salt products and contribute to the production of high salt products such as fish sauce |

One very distinctive group of microorganisms not included here are the viruses. These lack a cellular structure and can only multiply within a susceptible living cell. They are much smaller than other microorganisms, have typical dimensions in nanometres as opposed to micrometres and contain only one type of nucleic acid (DNA or RNA). Some viruses pathogenic to humans can be transmitted by food and some which attack and use bacterial cells as their host (bacteriophages) can adversely affect starter bacteria used in food fermentations such as cheese making.

1.2 MICROORGANISMS AND FOODS

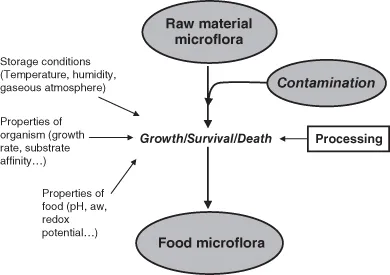

Foods are natural organic materials and as a consequence are rarely sterile. They carry a mixed population of organisms derived from the natural microflora of the plant or animal from which they originate and from the microorganisms that contaminate the food during harvesting/slaughter, processing, storage and distribution. The precise composition of this microflora will depend on the microorganisms present and whether they die, survive or multiply in the product up to the point at which it is consumed. Borrowing a term from ecology, a food’s microflora is frequently described as an association and is often characteristic of a particular food type (Fig. 1.1).

In most cases the presence of a food’s microflora will go unremarked by the consumer. Occasionally it becomes apparent, however, when it manifests itself in one of three ways:

- it causes illness;

- it causes spoilage;

- it produces desirable changes in the food’s sensory and/or keeping qualities.

1.3 FOODBORNE ILLNESS

Food has long been established as a vehicle for illness, and foodborne pathogens are described in detail in Chapter 2 of this volume. The precise mechanisms by which they cause illness can be very complex but in its broadest terms there are two fundamental scenarios. In the first, the organism grows in the food and produces toxin(s) which are then ingested along with the food, causing illness. This occurs with organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium botulinum and cereulide, the emetic toxin produced by Bacillus cereus, as well as some toxic secondary metabolites of fungi; mycotoxins such as aflatoxin produced by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. For toxin production to occur it is necessary for the organism to grow in the food and so these types of food poisoning can be prevented by ensuring that conditions in the food or its storage environment do not allow the growth of the pathogen concerned.

With other bacterial pathogens the pathogenic effect is elicited by the activity of the viable organism in the gut, so that living cells rather than a microbial product need to be ingested. The infectious potential of an organism will depend on a number of factors such as the particular strain of the organism, the food vehicle, and the susceptibility of the individual consumer. Strains differ in their virulence: some foods, particularly fatty foods, are thought to protect bacteria from antimicrobial barriers such as the stomach’s acidity, and foodborne illness can be much more severe in vulnerable groups such as the very young, the very old, the very sick, the immuno-compromised and, in the case of listeriosis, pregnant women and their babies.

Infectious potential can be described in the form of a dose–response curve which relates the ingested dose of an organism to the chances that it will cause illness, although in practice there is often insufficient data available to produce such curves with any great confidence (Holcomb et al. 1999). Since risk is related to dose, if the pathogen is able to grow in a food then the risk of its causing illness will increase. However, unlike those organisms that produce a toxin in the food, it is not essential that infectious pathogens grow in the food, and mere survival may well suffice to cause illness. If conditions prevent growth but do not necessarily inactivate the organism, as for example in a dried food, then risk will not increase but remain static. Examples of this situation have been noted with outbreaks of Salmonella and E. coli O157 infections caused by acidic products such as apple juice and home-made mayonnaise where the organism cannot necessarily grow but was able to survive in sufficient numbers to cause illness (Besser et al. 1993; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1975, 1996; Lock and Board 1995).

In most cases foodborne illness is characterised by symptoms restricted to the gastrointestinal tract such as some combination of naus...