- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy and Vocational Rehabilitation

About this book

This book introduces the occupational therapist to the practice of vocational rehabilitation. As rehabilitation specialists, Occupational Therapists work in a range of diverse settings with clients who have a variety of physical, emotional and psychological conditions. Research has proven that there are many positive benefits from working to health and well-being. This book highlights the contribution, which can be made by occupational therapists in assisting disabled, ill or injured workers to access, remain in and return to work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Understanding Vocational Rehabilitation

In this first chapter we want to start the process of demystifying what vocational rehabilitation (VR) is, and move forwards with a shared understanding of the activities and interventions which may come together under its umbrella. We also want to reflect on how we might draw on existing knowledge sources, some of which will already be very familiar to occupational therapists, in order to begin working towards creating a uniquely occupation-focused perspective of work and VR.

As we do so, let us remind ourselves that the essence of occupational therapy (OT) is built on a belief in the necessity and value of occupations. Each of us strives, throughout our life, to achieve a balance of meaningful and purposeful work, rest, self-care and leisure activities. Of all the occupations in which we engage across our lifespan, work arguably occupies the most central position. Work provides us with a significant life role that accounts for up to a third of the life of an average adult. Furthermore, the links between work and health, well-being and longevity, have already been well-argued (Wilcock, 1998). Despite this understanding, far too few occupational therapists in the UK today, ask the ‘work question’, even when they have clients who are of working age. Fewer still are involved, to any great extent, in addressing the actual work or employment needs of their clients. People outside of the profession could be forgiven for questioning why occupational therapists don’t deal with, perhaps, the most commonly recognised occupation.

But all this is changing. A growing recognition of the potential roles for occupational therapists within VR in the UK is fueling interest in learning more about this topic. The starting point must, of course, be with our shared understanding of VR itself, so let us examine what is meant by this.

DEFINING VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION

It is fair to say that, to many, ‘vocational rehabilitation’ is an unfamiliar term. It is also unpopular, with somewhat dated, value-laden connotations attached to it. The notion of a ‘vocation’ conjures, perhaps for some, images of religion. In popular language the word has often been associated with a calling to a certain profession – your vocation in life. ‘Rehabilitation’ fares little better, since nowadays it is frequently applied to strategies aimed at reducing criminal behavior and offending rates. It is also increasingly used in connection with expensive clinics, where celebrities enter ‘rehab’ to go through detoxification for a substance addiction. These images are unfortunate, since the terminological confusion which they create hinders understanding, as well as having the effect of positioning VR away from ordinary, everyday problems and interventions.

With the perceived unsuitability of this terminology, it is probably unsurprising that occupational therapists have sought out alternatives. This has resulted in a plethora of terms which largely describe a similar range of interventions, none of which seems to have successfully captured the essence of practice in this field. In the American literature we find frequent references to ‘work rehabilitation’, in Australia and New Zealand we find ‘occupational rehabilitation’ and ‘injury management’, in Canada ‘vocational practice’ and ‘disability management’. Attempts have been made in the UK to group the range of interventions which make up VR under the broader heading of ‘work practice’ (Pratt and Jacobs, 1997). In some countries ‘vocational rehabilitation’ is used to describe interventions only undertaken with those who are returning to work, since, strictly speaking, job seekers who have never worked, would more aptly be participating in habilitation, rather than rehabilitation. Confusingly, in yet other countries, VR is predominantly undertaken with those who are currently out of work, but may perhaps have worked in the past.

Unfortunately, if we extend our discussion beyond OT, the situation becomes even more complicated, since ‘vocational rehabilitation’ has different meanings to different groups of people. As well as the perceptions of the general public, others such as employers, insurers, health professionals, and politicians, each have their own take on what VR is, the purpose it serves, and frequently their own associated jargon.

Not only are there terminological differences, but there are similar disagreements about what VR actually entails. Some may describe it as a type of process. Kumar (2000), for example, introduces it as a multi-disciplinary process. Others may view it narrowly as a particular type of service model, which takes its place alongside work hardening and injury management programmes, or sheltered employment provisions (Perron and McKay, 1997). Alternatively, it may be used to describe an array of services. Commonly it is seen as a form of intervention, perhaps directed towards assisting somebody back to work. We will not resolve these terminological or ideological conflicts, nor will we attempt to try. The reader who consults the international literature does, however, need to be aware that these idiosyncrasies exist.

In acknowledging these global difficulties, let us now look at two of the, perhaps, most widely accepted definitions of ‘vocational rehabilitation’ within the UK context. The first was put forward by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) as part of a document entitled Building Capacity for Work: A UK framework for vocational rehabilitation (2004, p.14), and describes it as follows:

- Vocational rehabilitation is a process to overcome the barriers an individual faces when accessing, remaining or returning to work following injury, illness or impairment. This process includes the procedures in place to support the individual and/or employer or others (for example, family and carers) including help to access VR and to practically manage the delivery of VR; and

- in addition, VR includes the wide range of interventions to help individuals with a health condition and/or impairment overcome barriers to work and so remain in, return to, or access employment. For example, an assessment of needs, re-training and capacity building, return to work management by employers, reasonable adjustments and control measures, disability awareness, condition management and medical treatment.

The second is from the British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine (BSRM) (2003, p.1) who describe it as:

… a process whereby those disadvantaged by illness or disability can be enabled to access, return to, or remain in, employment, or other useful occupation.

You will note from these definitions, that they share a common perspective of VR as a process, designed to assist those with work goals, regardless of whether they are seeking to enter or remain in work. In addition, according to the first definition, it also covers a range of possible interventions as well, thus allowing the term to be used interchangeably. The DWP definition does, however, focus specifically on employment, whereas the BSRM suggests a wider understanding of work.

Having reached an understanding on what we mean when we talk about ‘vocational rehabilitation’, let us now briefly consider the sources of knowledge which we may draw on in order to effectively practice within it.

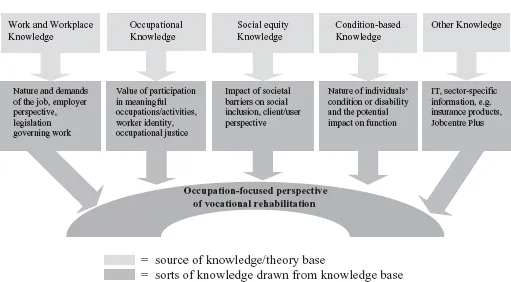

Figure 1.1 broadly depicts the main types of knowledge that occupational therapists may use in this field. Some will already be familiar, others perhaps less so. At the top of the figure there are two rows of boxes. We can see that the five boxes in the top row identify the sources of knowledge which occupational therapists may use in their VR practice. These include knowledge of work and the workplace, and knowledge about human occupation, drawn mostly from the occupational science paradigm. They also include social equity knowledge which helps us think about issues such as environmental barriers and the stigma which often faces disabled people who want to work. In addition, condition-based knowledge helps the practitioner to understand the nature of an individual’s illness or disability and the impact of this condition on their functional performance. Finally, the occupational therapist must draw on other sources of knowledge, such as information technology, as well as knowledge specific to the sector in which they are practising. For example, an occupational therapist working in the insurance sector may need to understand insurance products and the claims management process, whereas a practitioner in the voluntary sector, or in a condition management programme, would not. In the second row of boxes, we are given examples of the sorts of knowledge which occupational therapists may potentially draw from these respective knowledge bases.

Figure 1.1. An occupation-focused perspective of vocational rehabilitation

All these sources of knowledge collectively contribute to what has been termed ‘occupation-focused practice’. Occupation-focused practice is represented in this diagram by an arc. The arc itself represents the way in which OT may act as a bridge between employers, doctors, clients and others involved in the VR process. Occupation-focused practice draws on these different forms of knowledge so as to support the client to engage in the occupation of work in a way which is meaningful and purposeful to them. It is tempered by the need to have a commercial awareness of the realities of the workplace and the barriers which may act as obstacles to achieving this. Each of the different forms of knowledge identified here will be discussed further, in detail, in later chapters of this book. It may be worth reflecting at this point, on the key areas in which you wish to boost your own understanding of occupation-focused practice in VR.

2

The Evolution of Vocational Rehabilitation

This chapter begins with the earliest uses of occupation, and work, as therapy. Over the course of time there have been dramatic changes both to the role of the worker and the nature of work. The ways in which we, as a society, have organised, structured and performed this work, have also seen great transformations. Once considered to pose a significant risk to health, and even to life itself, work is now seen to have a positive effect on health and well-being. This short journey through time illustrates the ever-shifting relationship between the occupational therapy (OT) profession and the world of work.

The link between therapy, work and health, has always been influenced by wider societal attitudes to work, leisure, unemployment, poverty and health (Jackson, 1993). By gaining a clearer perspective of factors such as the health of the workforce and of the population at large, changing gender roles, economic and social issues, and public health priorities, we can gain a greater understanding of the interwoven history between OT and work. The purpose of this chapter, then, is to illustrate how these factors, and others, have impacted on the practice of OT in vocational rehabilitation (VR) in the past. In later chapters we can then explore how these factors may continue to influence our practice today.

Throughout this chapter, the challenges faced by previous generations of occupational therapists are clearly evident. Addressing the health needs of workers was not easy for the women who were the pioneers of OT. The injuries and health conditions which they were faced with were often very different from those seen today. The availability and range of treatments was very limited – there were few effective medicines and the cost of healthcare was beyond the reach of many. Work was risky and there were few safe-guards for workers. Over the course of time, OT has, out of necessity, had to evolve to meet the changing demands and needs of different client groups in different settings, as it continues to do today.

This chapter demonstrates how, at certain times in our history, there has been a strong OT focus on assisting disabled or ill workers. At other times, as seen in recent decades in the UK, there has been little or no involvement at all. This shifting emphasis has societal, political, and economic roots. By exploring these origins and influences, we may begin, perhaps, to anticipate potential future trends which may impact on the growth, and perhaps even the survival, of the profession in the future. You will note, as this chapter unfolds, how early occupational therapists faced particular challenges because of the established gender roles of the time. The dominance of the medical profession, together with tremendous medical advances, has exerted a particularly strong influence on the direction taken by OT. However other events, such as two world wars, economic recessions, and the advent of the welfare state, have also played a part in determining the involvement of occupational therapists in workplace health and workers’ rehabilitation.

The chapter will conclude by outlining how changes in the political and economic climate have, once again, put VR firmly on the agenda. These favourable conditions mean new and exciting opportunities. The challenge for occupational therapists is, once again, to refocus. In order to make effective use of the growing body of professional knowledge about human occupation, and the value of decent work to health, occupational therapists need to be ready to meet societies’ growing requirement to address the work needs of ill and disabled people.

THE EARLIEST USES OF OCCUPATION AS THERAPY

It has been suggested that the early use of occupation as therapy began alongside the introduction of moral treatment to mental asylums in the mid-16th to mid-19th centuries (Barris et al., 1988). This is not strictly true, since the use of activity to enhance physical and mental health, and well-being, stretches back to far earlier times. In fact, the therapeutic use of occupation can be traced back through the ages (MacDonald, 1970). Occupations such as work, exercise and recreation have been used in both Eastern and Western cultures to improve health and well-being (Paterson, 1997a). In ancient Chinese cultures, for example, physical training was used for the promotion of health. The Greeks reportedly made use of remedies such as music, wrestling and riding. Even as early as 30BC, employment was recommended for mental agitation. Alternating work and play was recognised as improving dysfunctional thought patterns as well as creating a sense of well-being (Primeau, 1996).

Many more examples of past uses of the healing powers of therapeutic activity can be found in the literature. The purpose of this chapter, however, is not to delve into the use of occupation as therapy, nor to expand on the origins of OT itself. Instead, it charts the relationship across time, between OT and the occupation of work. It begins with the therapeutic use of work in 18th century asylums.

MORAL TREATMENT, OCCUPATION AND WORK

In western Europe, towards the end of the 18th century, a new political agenda emerged in response to changing societal attitudes and reforms (Quiroga, 1995). A clear example of this shift in attitude was seen in the way mentally ill people were treated. They had previously been subjected to harsh medical remedies, such as regular bleeding, vomiting and purging, and were chained up in prison-like institutions. Then a new era of ‘moral treatment’ emerged (Paterson, 1997a). Society began to believe that there was a moral obligation to care for the mentally ill. People with mental illness deserved compassion and could not be held responsible for their actions. They were deemed as needing a cultural way of life, and opportunities for involvement in their everyday world, regardless of having a mental illness (Barris et al., 1988). The strong puritan influence of the time supported the use of work; viewing it as a positive and beneficial activity (Harvey-Krefting, 1985).

These contemporary perspectives brought about significant changes within asylums. Patients were freed from restraining chains and physical exercise and manual occupations were prescribed as innovative, new forms of treatment. These changes were implemented across the western world. For example, work treatment programmes were introduced into an asylum for the insane near Paris, France. Similarly, The Retreat, a psychiatric hospital in York, England, used employment to restore order within the asylum (Morrison, 1990). As these moral treatment approaches became more widespread, so too did the range and breadth of the occupations available to patients. This was particularly so in private institutions which served more affluent patients, since moral treatment did not extend to those who were considered paupers (Harvey–Krefting, 1985). Sir William Ellis, an English psychiatrist who was ahead of his time, highlighted the link between poverty, unemployment and insanity in the mid-1830s. In an attempt to combat this destructive cycle, he introduced the ‘gainful employment’ of patients in his asylum on a large scale. He recognised that individuals needed to be prepared for employment after discharge, so as to prevent relapse (Paterson, 1997b). Much of modern day thinking around social inclusion reflects similar values and ideals.

Early use of work activities was largely in keeping with class and gender norms of the time (Bracegirdle, 1991). Women tended to be occupied by domestic work in the kitchens or sewing, knitting or crochet. Garments made were often sold. Men were involved in manual work such as horticulture, bricklaying, blacksmith work, basket making and tailoring. These work activities had a primarily restorative purpose and any economic benefits to the institution were, at that time, of only secondary importance (Hanson and Walker, 1992). Indeed, occupation was not only used in the treatment of the mentally ill. The ideals behind moral treatment extended beyond the asylum and so there was widespread interest in employment opportunities for physically disabled people too. Trade schools and other training workshops were developed, and served much the same purpose as sheltered workshops of more recent times. Workshops for blind people offered music, crafts and work projects. Products made were sold, but the main purpose was to give structure and purpose to the lives of individuals, rather than financial independence (Harvey-Krefting, 1985).

Unfortunately, however, the progressive changes of the moral treatment era were short-lived:

- Increasing urbanisation and industrialisation contributed to growing numbers of chronic patients entering asylums. By the mid- to late 1800s, asylums had increased to such a size that they had become unwieldy. There were over 100,000 inmates, and still more in workhouse infirmaries (Hardy, 2001).

- At around this time, public attitudes began to change. The humanist values underpinning moral treatment were replaced by a philosophy which emphasised the personal responsibilities of the individual.

- Medical opinion of mental illness became dominated by a biological perspective. This led to pessimistic beliefs about the poor long-term prognosis of what was, at the time, viewed as a disease of the brain (Harvey-Krefting, 1985).

Given these pressures, reform could not be sustained. By the turn of the century, many institutions were unable to provide much more than custodial care. As moral treatment died out, so too did much of the early promise of the use of work and occupation as forms of therapy. It wasn’t until after the First World War that productive work returned to asylums on a large scale.

WORK IN THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES

In this section we will turn our attention to exploring what work was like in the past. In doing so, we learn that work was a very different experience from that of nowadays. Although accurate records do not exist, estimates suggest that in Britain before 1755, the occupational structure was quite stable. The pace of work was relatively slow and up to a third of the year consisted of holidays for religious celebrations, festivals, weddings, carnivals and funerals. Change began with a rapid increase in the two largest industries, agriculture and manufacturing, during the second half of the 18th century. Other economic activity took place in the smaller industries of commerce, building and mining. At about the same time religious reformers, such as Puritans, began to reject existing work patterns and introduced a harsher regime, consisting of six days of work and one of rest. It was believed this was an essential way to improve humanity (Primeau, 1996). It is important to bear in mind that although work has come to be associated with dignity and status in modern times, in the past it used to invariably involve pain and degradation (Berg, 1987) and was very much used as a means of social control. Workers were afforded few protections and industrial accidents were commonplace. The risks of injury and even death were very real. Many of these issues still confront workers in developing countries today.

THE PLACE OF WOMEN IN THE WORKFORCE

Work at this time was traditionally divided by gender. Women and children made up a large percentage of the workforce in some industries. For example, in late 18th century Britain the largest, most dominant sector within manufacturing was the textile industry. Textiles produced included wools, linen, silk, lace, hand and framework knits, and cotton. Across this sector, women and children did most of the work tasks. This type of work took place in small, individual textile industries and in the home, within the family economy. Other significant manufacturing industries included leather trades and metalwork industries. These, together with the building and coal industries, were the domain of men. Mixed trades did, however, exist within the iron and brewing sectors (Gray, 1987).

As mechanisation increased, there were reduced opportunities in many industries, and a drop in earnings followed. It is recorded that a good spinner in the linen industry in Scotland, working a 12-hour day, could produce 11/2 spindles per week. But even working these long hours, she wasn’t able to cover the price of her food, clothing and rent. Whereas during the pre-industrial and early industrial periods, the employment of women in the trades was widespread (Gray, 1987), this all changed with high levels of male unemployment and a glut of trades. Work shortage resulted in the barring of women from many trades, as well as from higher-paid work in the textile industry. In addition, increasing industrialisation led to much of the available employment moving away from the home. This shift, combined with restricted roles within the trades, produced a far greater split in the division of labour than had previously existed. The changes also contributed to widening pay inequities. Domestic labour became the forced option for many women, particularly in more rural areas (Berg, 1987) .

TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE

Across these two centuries, division of labour was also influenced by new,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction

- 1 Understanding Vocational Rehabilitation

- 2 The Evolution of Vocational Rehabilitation

- 3 The Meaning and Value of Work

- 4 Theoretical Frameworks in Vocational Rehabilitation

- 5 Service Models in Vocational Rehabilitation

- 6 Occupational Therapy and the Vocational Rehabilitation Process

- 7 Vocational Rehabilitation for Specific Health Conditions and Disabilities

- 8 Team Structures in Vocational Rehabilitation

- 9 Working within the Law in Industry

- 10 Future Directions

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Occupational Therapy and Vocational Rehabilitation by Joanne Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Occupational Therapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.