- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy in Oncology and Palliative Care

About this book

Now in its second edition, this is the only book on occupational therapy in oncology and palliative care. It has been thoroughly updated, contains new chapters, and like the first edition will appeal to a range of allied health professionals working with patients with a life-threatening illness.

The book explores the nature of cancer and challenges faced by occupational therapists in oncology and palliative care. It discusses the range of occupational therapy intervention in symptom control, anxiety management and relaxation, and the management of breathlessness and fatigue.

The book is produced in an evidence-based, practical, workbook format with case studies. New chapters on creativity as a psychodynamic approach; outcome measures in occupational therapy in oncology and palliative care; HIV-related cancers and palliative care.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What is Cancer?

Cancer is a general term applied to tumours or growths. The terms oncology, anaplasia, neoplasms may all be used as an alternative to the word cancer. Body cells normally regenerate and die continually so the number of cells remains constant. Cancer is the disordered and uncontrolled growth of cells within a specific organ or tissue type. If left untreated, they grow steadily resulting in a mass, tumour or growth. The tumour may be benign or malignant. Benign tumours grow slowly and do not recur after excision. They can still be life-threatening if untreated as they can affect vital organs. They are usually curable if they are treated early.

The human body is made up of 10 trillion cells (Knight, 2004), and there are over 100 different types of cells. 25 million cells are replaced every second in adult life. All cells replicate themselves, usually 50–60 times before cell death. Malignant cells grow in an irregular pattern (Gabriel, 2004, p. 4). The smallest detectable tumour is approximately 1 cm in diameter and already contains 1 billion cells. Normal cells know when to grow, to specialize (differentiate), to die (apoptosis), to release certain products or proteins needed by other cells to grow and how to build complex tissue structures.

Cancer is not a single disease but a complex sequence of events (Haylock, 1998). Cancers not only develop at a single site, but also result from malignant change within a single clone, or cluster, of cells. This then multiplies and acquires different changes that give it a survival chance over its neighbours. Cancer cells develop when they have defects in regulation that govern normal cell proliferation and homeostasis, i.e. they lose the ability to die and continue to multiply.

Tobias and Eaton (2001) describe how several steps are required before a normal cell becomes a malignant one. Cell growth and division is profoundly influenced by the presence of critical genes. Oncogenes drive the cell towards malignancy and suppressor genes mutate and result in a loss of normal regulatory or restraining function.

Woodhouse et al. (1997) describe the process by which cancer cells spread or metastasize:

- angiogenesis: the generation of blood vessels around the primary tumour that increases the chances for tumour cells to reach the blood stream and colonize in secondary sites;

- attachment or adhesion: tumour cells need to attach themselves to other cells and/or cell matrix proteins;

- invasion: tumour cells move across the normal barriers imposed by the extracellular matrix;

- tumour cell proliferation: new colony of tumour cells is stimulated to grow at a secondary site.

Malignant tumours, therefore, infiltrate and destroy the normal tissues surrounding them and spread to other sites either by blood or the lymphatic system. These are then called metastases or secondaries.

Although terminal and palliative care are phrases often used interchangeably, terminal actually refers to individuals who are actively dying so likely to be in the last few days of life. A diagnosis of cancer does not necessarily mean that the disease will become terminal and the phrase terminal illness can refer equally well to the end stages of neurological, viral or respiratory illness.

Palliation refers to the alleviation of symptoms rather than the attempt to cure disease and it is associated with the advanced stages of all diseases including cancer and HIV/AIDS. The World Health Organization (WHO) (1990) defines palliative care as ‘the active total care of patients and their families by a multiprofessional team when the patient’s disease is no longer responsive to curative treatment.’ In occupational therapy there is not a finite point between acute and palliative care. The focus may change from one to the other as the client progresses or deteriorates. Symptoms are approached in a similar manner and treatment depends on the client’s functional status. Dysfunction may be the result of the tumour and/or side-effects of medical intervention such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery.

CLASSIFICATION OF TUMOURS

Tumours are classified according to histogenesis – the tissues and cells where they originate. Cancers are often described in terms of degrees of differentiation. The tumour’s degree of differentiation is the extent to which it resembles the normal tissue from which it is derived. If it closely resembles the normal tissue it is well differentiated, otherwise it is poorly differentiated. When tumour cells lose all similarity to the corresponding normal tissue, they are referred to as undifferentiated or anaplastic. Tumours of the muscle and connective tumours are classified as in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Nomenclature of connective tissue and muscle tumours

| Tissue of origin | Benign tumours | Malignant tumours |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibroma | Fibrosarcoma |

| Adipose (fatty) tissue | Lipoma | Liposarcoma |

| Bone | Osteoma | Osteosarcoma |

| Cartilage | Chondroma | Chondrosarcoma |

| Connective tissue near joints | Benign synovioma | Synovial sarcoma |

| Blood vessel endothelium | Haemangioma | Haemangiosarcoma |

| Lymph vessel endothelium | Lymphangioma | Lymphangiosarcoma |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

| Striated muscle | Rhabdomyoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

(From Gowing and Fisher (1989) cited in Cooper (1997))

INCIDENCE

The incidence of cancer is increasing possibly due to lifestyle and the increasing age of the population (Gabriel, 2004, p. 11). There are 1 : 250 men and 1 : 300 women diagnosed as suffering from cancer every year (Souhami and Tobias, 2003). As the elderly population grows and as more people with cancer live longer due to better treatment, there are increasing numbers of people with residual dysfunction and disabilities who require occupational therapy. Although the treatment and management of the primary tumour have obviously been the main focus of medical input, metastatic spread is still the main cause of death (Woodhouse et al., 1997). This spread often develops before diagnosis and treatment have begun, so prognosis is not altered by treatment of the primary cancer.

The highest recorded incidences of cancers in females in England in 2002 are breast, lung and colorectal cancers. Those in males are prostate, lung and colorectal cancers (Office for National Statistics, 2005). Early intervention with cancer treatment invariably has a better chance of survival.

AETIOLOGICAL FACTORS

In many types of cancer there is still no clear evidence of what triggers the initial malignant change. Some factors are known: they are listed in Table 1.2.

Diet is emerging as an increasingly important risk factor for lower bowel cancers.

Table 1.2 Aetiology of cancer

| Ionizing radiation | |

| Atomic bomb and nuclear accidents | Acute leukaemia and breast cancer |

| X-rays | Acute leukaemia, squamous cell skin carcinoma |

| Ultraviolet irradiation | Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell skin carcinomas, melanoma |

| Background irradiation | Acute leukaemia |

| Inhaled or ingested carcinogens | |

| Atmospheric pollution with polycytic hydrocarbons | Lung cancer |

| Cigarette smoking | Lung cancer, laryngeal cancer, bladder cancer |

| Asbestos | Mesothelioma, bronchial carcinoma, lung cancer |

| Arsenic | Lung cancer, skin cancer |

| Aluminium | Bladder cancer |

| Aromatic amines | Bladder cancer |

| Benzene | Erythroleukaemia |

| Polyvinyl chloride | Angiosarcoma of the liver |

(From Cooper 1997)

SYMPTOMS

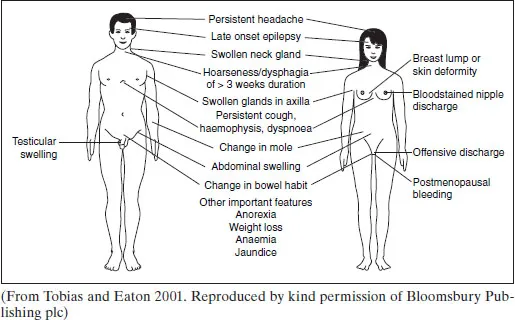

Figure 1.1 Common symptoms and signs of cancer

INVESTIGATIONS

SCREENING

Breast and cervical cancer screening is well established; breast cancer screening is only certain for females aged over 50 years. Cervical screening programmes are offered as often as resources allow. Trials have failed to show efficacy for lung cancer screening, and testicular cancer has such a good cure rate that screening could only enhance prognosis.

STAGING

Staging identifies the stage that the disease has reached and is one way of establishing the factors that are likely to influence prognosis in any individual. The TNM system evaluates the tumour by size, lymph node spread and presence of distance metastases:

T – tumour size, site and depth of the primary tumour’s invasion depending on the type of tumour, evaluated on a scale ranging from T1–T5;

N – lymph node spread, evaluated on a scale ranging from N1-N5;

M – the presence of distance metastases, evaluated on a scale ranging from M1-M5;

e.g. T3, N1, M0 laryngeal cancer implies a primary tumour sufficiently locally advanced to have affixed the vocal cord and early lymph node invasion causing a palpable swelling in the neck but no evidence of metastastic spread.

OTHER INVESTIGATIONS

The individual undergoes many of the following investigations in order for diagnosis and treatment procedures to be established:

- x-ray

- blood counts

- enzymes

- ultrasound

- computed tomography (CT) scan

- positron emission tomography (PET) scan

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

- isotope scanning

- surgery.

TREATMENTS/INTERVENTIONS

SURGERY

Cancer surgery is classified as:

- diagnostic and staging – biopsy taken. Primarily curative, where local control of cancer is essential as the primary site either causes or contributes substantially towards death;

- adjuvant – used alongside chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy;

- prophylactic – laser surgery to remove premalignant cells and preventing further tumour growth;

- reconstructive – to rebuild areas removed by other surgery;

- palliative – used in symptom control if a tumour compresses other areas or a nerve block is required for pain control;

- emergency – to remove a life-threatening obstruction;

- surgery for metastases;

- surgery for vascular access – insertion of Hickman line (central intravenous line) in the superior vena cava or right atrium through which chemotherapy can be given. Also insertion of feeding gastrostomy;

- laser surgery.

RADIOTHERAPY

Radiotherapy is the use of ionizing radiation to destroy cancer cells. The aim is to destroy or inactivate cancer cells while preserving the integrity of normal tissues within the treatment field. It is often able to control the tumour with minimal physiological disturbance. There are different types of radiotherapy, and these should be matched to the individual’s diagnosis and needs. The factors taken into account when planning radiotherapy include the type and stage of tumour, localization of tumour and adjacent normal structures.

Detailed planning is needed and this may include the preparation of an individually moulded cast. The individual wears this during radiotherapy and it positions him or her correctly. The exact positioning and dosage of radiotherapy is calculated. Radiographers position the individual on the couch, using marks made on the skin in indelible ink, and the radiation beam is switched on. Radiographers or radiotherapists observe the individual via a window or closed-circuit TV in the treatment area, using an intercom for communication.

Radiotherapy is used alone or adjuvant to surgery and/or chemotherapy. In addition to treating localized tumours it is often used as a palliative treatment to relieve pain or bleeding, or to suppress bone metastases which are developing into pathological fractures. Side-effects may include:

- fatigue and malaise, sometimes caused by bone marrow depression;

- anorexia, nausea and vomiting;

- alopecia;

- inflammation around the site being treated, causing internal side-effects such as mucositis, oesophagitis, laryngitis, diarrhoea, cystitis;

- anxiety and altered body image.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy is the use of cytotoxic (cell poisoning) drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy cancer cells by interfering with the cells’ ability to grow and divide. Although normal cells can be damaged, most healthy tissue grows back again.

Chemotherapy can be used in the following ways:

- neo-adjuvant – given prior to surgery to shrink the tumour with the aim of making surgery easier as there is less tumour and increased likelihood of cure;

- adjuvant – in combination with radiotherapy or surgery to eliminate micrometa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 What is Cancer?

- 2 Challenges Faced by Occupational Therapists in Oncology and Palliative Care

- 3 Occupational Therapy Approach in Symptom Control

- 4 Occupational Therapy in Anxiety Management and Relaxation

- 5 Occupational Therapy in the Management of Breathlessness

- 6 Occupational Therapy and Cancer-Related Fatigue

- 7 Client-centred Approach of Occupational Therapy Programme - Case Study

- 8 Occupational Therapy in Paediatric Oncology and Palliative Care

- 9 Occupational Therapy in HIV-related Cancers and Palliative Care

- 10 Occupational Therapy in Neuro-oncology

- 11 Occupational Therapy in Hospices and Day Care

- 12 The Use of Creativity as a Psychodynamic Activity

- 13 Measuring Occupational Therapy Outcomes in Cancer and Palliative Care

- Appendices

- REFERENCES

- Glossary

- Glossary-Abbreviations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Occupational Therapy in Oncology and Palliative Care by Jill Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Occupational Therapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.