![]()

CHAPTER 1

Finding a voice: the development of children’s healthcare

Sarah Redsell and Cris Glazebrook

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter we review the development of understanding of children’s needs as recipients of healthcare. We begin by describing how basic public health measures implemented during the Victorian era led to improvements in the length and quality of children’s lives. Then we consider children in hospital and the origins of the restricted parental visiting policy introduced by the Victorians to prevent infection. We describe the work of scientists like John Bowlby and reformers like James Robertson who sought to persuade hospitals to take account of the emotional, as well as the physical, needs of sick children. Our chapter also looks at different approaches to the care of children in hospital and explores policy changes that have allowed for greater involvement of children in healthcare.

PUBLIC HEALTH REFORM

Children’s healthcare has traditionally been regarded as both protective and curative. The protective component concerns the prevention of ill health through public health measures, such as the provision of safe drinking water, sanitation and immunisation. Curative medicine relates to the treatment of particular diseases. In the UK the reforms to public health that were undertaken over 150 years ago were the first step towards increasing children’s health and life expectancy.

The Industrial Revolution began towards the end of the eighteenth century. Many people moved from the countryside to the towns and cities to work in factories. In a relatively short space of time the UK economy was transformed from agricultural to industrial production.1 Unfortunately, the existing social structures of housing, policing, education and public health lagged behind the technological advances that were being made in transport and technology.1 The population doubled in the first 50 years of the nineteenth century from 9 million to 18 million.2 The already existing public health problems – a lack of clean water supply, sanitation and sewage disposal – were worsened by the increased urbanisation.2 Poor living conditions, malnutrition and ignorance (in terms of health, hygiene and medical treatment) resulted in the population being in poor health by today’s standards.

Insanitary conditions had always been present in the towns and cities but they were made worse by the population acceleration.2 People of all ages often shared rooms in damp, filthy houses and tenement buildings. There was no sanitation and only a few houses had running water. Water was usually obtained from a pump or standpipe serving several streets and only available for a few hours a day.2 Domestic and industrial refuse and sewage were disposed of in the street and collected infrequently. Infection spread more rapidly through the urban areas and communicable diseases such as smallpox, typhus and tuberculosis were endemic. There were epidemics of cholera and scarlet fever.3 In 1850, the death rate for children living in urban areas was much higher than for those living in rural areas.4 Life expectancy during the mid nineteenth century was 18–25 years in the industrial areas and 40 in the countryside,2 which is considerably shorter than the least developed countries in the world today.

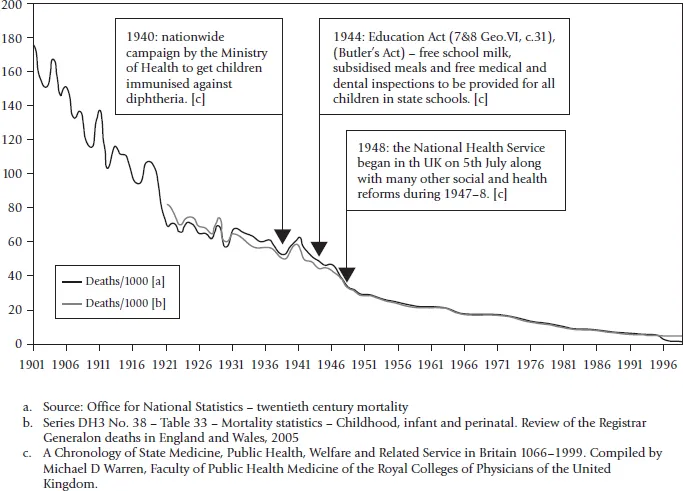

High rates of poverty resulted in a poor diet both in terms of food quality and quantity. Consequently, malnutrition was commonplace among poorer children, with many suffering from rickets.4 These malnourished children were more susceptible to the ever-present threat of infectious disease. There was a good deal of ignorance about health and hygiene in the home, as well as medical ignorance about the treatment of infectious diseases and accidental injuries. Newborn babies who could not be breast-fed were at particular risk of dying of infection introduced by the mother’s dirty hands or infected cow’s milk.5 Attacks of gastro-enteritis were common and severe diarrhoea in malnourished children often led to dehydration and death. Every backyard contained refuse and sewage and became a breeding ground for flies, which carried disease into the food chain.5 Figure 1.1 outlines the total infant mortality rates for England and Wales, 1901–99.6 It is worth noting that during the hot summers (i.e. in 1911) the mortality rates rose due to the numbers of infants contracting diarrhoea from poorly stored food.

Children’s well-being was not seen as the responsibility of the state.4 In fact, the state took no responsibility for public services during the early Victorian era. State or charitable intervention was frowned upon and individuals were expected to take responsibility for themselves.4 However, there was acknowledgement that something needed to be done to stop the spread of infectious disease, particularly in the industrial areas. Victorian social and administrative reformers believed that the root causes of infectious diseases needed to be tackled and initiated a widespread overhaul of water, sewage and drainage facilities.1 Slowly legislative changes were introduced and control of public health became a matter for local and central government.2 Eventually, water supply, sanitation and sewage disposal became the responsibility of statutory authorities.1 These efforts gradually reduced the likelihood of disease epidemics and made a major contribution to increasing life expectancy.1 Figure 1.1 shows the impact of these changes on infant mortality rates.6

FIGURE 1.1 Total infant mortality, all causes, per 1000 (infants) – England and Wales, 1901–99

The public health debate today

Public health policies are useful in providing us with an understanding of how to prevent ill health and promote good health. However, the debate about state versus individual responsibility continues. Some public health policies imply that individuals should lead a risk-free life and there are those who wish to make their own choices, which may include an element of risk. Furthermore, making a risky choice may not always be an informed decision. There are many other factors involved in an individual’s decision to maintain an unhealthy behaviour. Health professionals working with children who are obese, for example, have to look beyond making recommendations to their parent(s) about a healthy diet. They may need to include an assessment of the parent’s ability to understand the seriousness of the situation, an assessment of their income and their ability to provide healthy foods, together with exploring the rewards for maintaining the situation. Sometimes the gap between public health aims and individuals’ lifestyle is vast.

There is now general agreement that poverty is a contributory factor in ill health. The most recent public health policy document, Choosing Health, emphasises the continuing need to tackle poverty and health inequalities, promote healthy living environments and healthy schools and to apply measures to help children and young people understand risky health behaviours.7 Current public health measures include health protection interventions, such as immunisation against infectious disease; health improvement interventions to tackle individual behaviours that contribute to disease risk, such as obesity, smoking, alcohol and drugs; and patient-safety interventions to prevent healthcare institutions from harming users.

HOSPITALS AND SICK CHILDREN

Institutions that care for the sick, poor or destitute have existed since the Roman era but it was only in the eighteenth century that modern hospitals began to appear.8 During the eighteenth century the Foundling Hospital was opened in London, which was specifically for sick and orphaned children. Once it became known that free healthcare could be obtained from the hospital sick children arrived from all over the country. Many young children and babies were abandoned at the hospital by their parents. The hospital became London’s ‘most fashionable charity’ but it struggled to attract sufficient funds to care for the increasing numbers of children arriving at its doors.4 Eventually it had to limit admissions to those children whose lives could actually be improved by the medical services on offer.4

By 1800, 35 voluntary hospitals had been founded in England and a further seven in Scotland. These were funded by wealthy benefactors who were publicly involved in their support.4 Voluntary hospitals were mainly for the deserving poor and the destitute. The wealthy, the ordinary working-class families and those receiving poor relief from the parish were expected to pay for their own treatment at home.4 Doctors who worked in these hospitals were largely self-supporting; often generating income by treating wealthy patients in their own homes. There were frequent disagreements between the medical staff and the hospital managers about what constituted ‘destitute’, with doctors unwilling to turn away deserving and interesting cases who did not fit the admission criteria.4

Poor sick children admitted to the voluntary hospitals were treated alongside adult patients.8 However, mixed wards were difficult for staff to manage and there were concerns about the number of drunk and disturbed cases being admitted at night and waking the children.4 Funds for the care of children were easier to attract when donors were certain their money would be spent only on the welfare of innocent, helpless children rather than adults suffering from what might be perceived as self-inflicted illnesses.4 Specialist children’s hospitals opened largely at the initiative of individual physicians seeking professional advancement rather than to meet a community need.4 The mortality rates in the early children’s hospitals were very high.4 Many of the deaths were young infants and babies of destitute parents who arrived at the hospitals extremely ill and malnourished. There was often little the hospitals could do to help the large numbers of poor, sick children requiring treatment.4

In the UK, one of the first specialist children’s hospitals was Great Ormond Street in London, which opened in 1852. The majority of its income came from its supporters through individual donations and subscriptions, a situation that remained until the formation of the National Health Service in 1948. The Admission Registers from 1852 to 1903 show the nature of children’s illnesses, treatments and outcomes during that time.3 The records suggest that children were often admitted to hospital with illnesses that were a consequence of their poverty and poor understanding about the transmission of infectious diseases. Children were treated for minor illnesses, such as catarrh and constipation, and life-threatening conditions, such as croup and rheumatic fever. Children were also admitted to the hospital w...