![]()

Chapter 1

The Development of Play

What is Play?

Ask a child what she has been doing and a likely reply is, ‘Just playing.’ As adults we may well leave it at that, going along with the idea that play is not an important matter compared with the real business of ‘work’. Yet I want to argue that play is essential, for children and adults alike, not simply as a means of relaxing but rather as a way of helping us make sense of the world and having some feeling of control over our lives.

As adults, most of us look forward to a chance to unwind, to a ‘breathing space’, to ‘recharge our batteries’, to ‘sort out our heads’. Yet the activities we choose – whether enjoying music, playing sports, seeing friends, reading the newspaper, having a bath, and so on – tend to feel most satisfying when our inner selves feel reaffirmed in some way, indicating, as some of these metaphors suggest, that a more creative process than just relaxing has been going on. Most of us are familiar with the mental freezing which can accompany pressure, whether self-imposed or from somebody else. If someone is explaining how to use a new computer we can feel more and more muddled, and can’t wait for them to go away so that we can ‘play’ on our own and gradually become more familiar with this new thing. We may find too that if we stop consciously thinking or worrying about a particular question we may be surprised to find an answer popping unexpectedly into our heads; our mind has been left to play, quietly wandering round the problem, and has found a solution. Play frees us from the fear of failure or disastrous consequences so that we are able to be inventive and creative. When we have heard some bad news we can feel mentally numb and want time on our own to ‘digest’ it, to ‘chew it over’, to understand what has happened, to become aware of how we feel and to rehearse how we might respond. We tend not to think of this as play, but play can be a serious business too. Maybe later we will want to talk it through, sometimes repeatedly, with someone else: this is like Winnicott’s play ‘in the presence of someone’ and offers an insight into the connection between adult counselling and play therapy.

So we have different kinds of play, some more obviously playful in feeling than others. All are to do with ways in which we consciously or unconsciously process our experiences, integrating them into our inner mental worlds. This brings a renewed feeling of things making sense, which in turn gives us a sense of autonomy, of things being manageable and under our control, at least as far as our own actions and responses are concerned. In the process we change ourselves and our view of the world. We dare to change because our self is not threatened. On the contrary, the process of playing gives the glorious sensation of a stronger sense of self. Play can be deeply satisfying.

As it is with adults, so it is with children. Making sense of the world is an enormous task for young children. But children have less autonomy than adults, and are often less able to find the words to express their thoughts and feelings. So play has a crucial significance for them. They are constantly at risk of being overwhelmed by events or feelings. Then ‘solitary play remains an indispensable harbour for the overhauling of shattered emotions after periods of rough going in the social seas’. For example, when my daughter was finding school stressful she would come home in a temper, disappear upstairs to play for an hour and re-emerge feeling much more settled. Like us, when we cannot take in an explanation of how to work something new, children often ignore the instructions (or our directions) that come with toys such as Lego, and play on their own – exploring, trying something, finding it doesn’t work, having another go. They are becoming familiar with the materials and making them their own, a creative and ultimately more satisfying process. Children who have had a difficult or distressing time, or who have suffered a painful separation or loss, may use play to help them come to terms with their experience. Unlike adults who can run things over in their minds, children need to externalize their thoughts through play. In pretend play children can safely bash, bury or throw away the people they are angry with or frightened of, or re-enact something that has happened, perhaps changing the outcome. The child brings into his play ‘whatever aspect of his ego has been ruffled most … To "play it out" is the most natural self-healing method childhood affords’ (Erikson 1965: 214–215). By re-enacting and repeating events, often in a symbolic form, and by playing out their own feelings and phantasies, children come to terms with them and achieve a sense of mastery. They can safely express anger and aggression without harming other people, or without it rebounding to harm themselves. As anxiety is relieved and inner harmony restored they become more able to manage real events.

The pleasure and excitement of playing, the intensity and concentration, the freedom to experiment, to explore and to create, to find out how things and people work and what you can do with them, to give the imagination free rein, and to fill the gap between reality and desire, all these derive from the fact that in play the child is in charge. Thus ‘play under the control of the player gives to the child his first and the most crucial opportunity to have the courage to think, to talk and perhaps even to be himself’ (Bruner 1983). Although play can be a serious as well as a joyous activity, the crucial condition is that errors do not have serious consequences. A child’s spontaneous play within a familiar setting is a different kind of experience from exploration of an unfamiliar and potentially frightening world. Risks can be taken because the play itself matters more than the results of play. Play can only take place within a safe boundary, providing both a time and a place, so that the child knows where play begins ‘and where it ends and the rules change back to everyday life’ (Skynner and Cleese 1983: 298). Huizinga (1949: 10–12) puts it more formally:

All play moves and has its being within a playground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of choice … All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart. Inside the playground an absolute and peculiar order reigns … the laws and customs of ordinary life no longer count.

For young children the boundary of their ‘playground’ is provided by parents or other adults who protect them from intrusion from the outside world. This may involve a special place, usually with familiar features or objects, or a special time, or both. When two or more children are playing together, or an adult is joining in as a player, they will normally indicate to one another that ‘This is play’. This may be a look, a ‘play face’, a laugh, or perhaps a verbal recognition such as ‘You pretend to be my mummy’. Play is paradoxical in that the interaction between players is real but the message between them is that what they are doing is not real (Bateson 1973). Inside the boundary the player can experiment with changing normal ways of categorizing things, often a source of humour as the child realizes this. Play can be a ‘special way of violating fixity’ (Bruner 1976: 31). For example, the child with a new baby in the family may take a delight in playing ‘mother’ whilst the real mother has to play the baby who, like Hansel and Gretel, gets sent off into the forest.

So play is children’s means of assimilating the world, making sense of their experience in order to make it part of themselves. Their experience also, of course, involves the opposite process of accommodation, learning to fit in with the demands of reality (Piaget 1951). The importance and excitement of play lie in its ability to link the real world and the inner mental world of the child. In play, children can transform the world according to their desires, especially a situation ‘in which the individual finds his self, his body and his social role wanting and trailing’. The child both imagines and practises being in control, ‘in an intermediate reality between phantasy and actuality’ (Erikson 1965: 204).

Social play with other children may have some of these healing qualities. The presence of others, however, means that play is often closer to the world of reality. Children may be involved in negotiating or coordinating their actions with one another. The demands of social interaction may sometimes inhibit the playing out of individual inner phantasies, unless the phantasies of several players coincide. The satisfaction of shared play may come from the enjoyment and excitement of play which reflects close relationships and mutual recognition. Yet where play involves a pecking order, those players with little power may find social play hurtful and even damaging. To summarize, the essentials for play are:

- safe boundaries – the need for the player to feel safe within a physical boundary of time and space, where the rules of everyday life do not apply, and to feel well enough held emotionally, whether or not an adult is actually present

- autonomy – the need for the player to feel in control of the play and the direction it takes, whether or not another person is present or playing

- no serious consequences – the process of playing matters more than the results; mistakes do not have serious consequences so that risks can be taken.

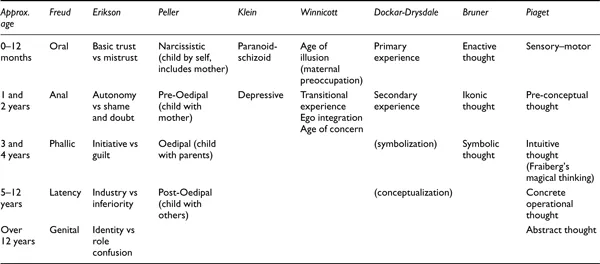

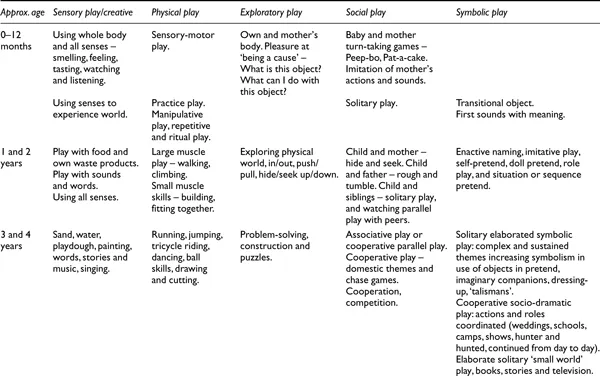

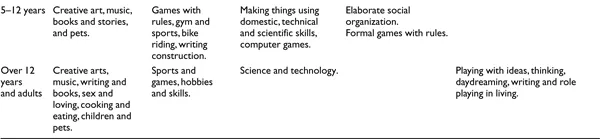

For many children such healing play takes place in the normal course of events, probably without adults being aware. The opportunity to play may be enough for the child whose life is not overwhelmingly disrupted or distressing, and when there is someone around who holds the child in mind, providing the emotional containment which helps them manage their anxiety. Children who have had too much going on in their lives can benefit from the active involvement in the play process of a concerned, aware and containing adult. This is where therapeutic play or specific play therapy sessions may help. When we are offering play help we need to think carefully about our provision and management of each of the essentials of play. How we provide them varies, depending on our assessment of the child’s needs. We will return to these questions. First, we need to understand the pattern of development of play so that we can recognize the developmental level a child has reached if we are to use play appropriately to help. The development of play is linked to aspects of physical, intellectual and, crucially, social and emotional development. Observations of spontaneous play are invaluable in diagnosis and assessment. The rest of the chapter describes children’s emotional and play development from birth to adulthood. This is summarized in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 (p. 34 and pp. 35–36).

Table 1.1 Stages in child development

Table 1.2 The development of play

The Beginning of Play in the Age of Illusion

Maternal Preoccupation, Attunement and Containment – ‘Good Enough’ Mothering

Donald Winnicott, celebrated paediatrician and psychoanalyst, used to advise parents who were fearful of the enormous responsibility of caring for their apparently helpless new baby that a baby is ‘a going concern’, with an inherent potential to live and develop. Yet he also observed that ‘there is no such thing as a baby, only "a baby and someone"’ (Winnicott 1964: 88). Psychologist Lynne Murray’s film (2000) shows how within an hour of birth the newborn watches and responds to his mother’s (and father’s) face. In the relationship between baby and mother (usually but not necessarily the biological mother – and there is no reason that mothering should not come from fathers or even be shared by a number of people) lies the foundations of a child’s emotional development. The baby’s intense feelings of pleasure and pain, of love and anger, are bound up with the mother.

Winnicott’s ‘good enough’ mother initially meets her baby’s needs totally. She is able to do this through her attunement (Stern 1985) and maternal preoccupation in which she ‘gives the infant the illusion that there is an external reality that corresponds to the infant’s own capacity to create’, making actual what the baby is ready to find (Winnicott 1971: 12). The baby sees themself mirrored in their mother’s face and builds up a picture of themself from their mother’s responses. The baby feels comfortably omnipotent rather than helpless. The mother’s gradual and inevitable failure ‘to perfectly accommodate herself to her baby’s every need enables the infant eventually to relinquish the illusion of unity and omnipotence’, to find their own ‘edges’ and to explore the reality of the outside world. A ‘perfect’ mother who remained totally adapted to her infant’s needs would not allow her baby to start to experience themself as a separate person.

Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s ideas are helpful in understanding what happens between mother and baby (Klein 1986; Waddell 2000). The baby’s first experiences of the world, pleasant or unpleasant, involve the whole body. Mental development requires the infant to sort and separate, or split, these sensory experiences into good and bad feelings. This gives a space in the baby’s mind where good feelings can be stored, to form the beginnings of the self. The baby splits off or gets rid of (or projects) the bad feelings by putting them into the mother, with a paranoid fear of their being returned, in the process losing touch with that part of the self. Klein called this the paranoid-schizoid position and saw it as part of normal development. It remains to a greater or lesser extent an underlying part of everyone’s personality; the tendency to blame and hurt others surfaces at times of stress.

The ‘good enough’ mother attends to her baby’s feelings, good and bad, to such an extent that she experiences them as if they were her own. Bion (1962) calls this process of being open to being stirred up emotionally by the baby reverie. (Most mothers will recall the compelling anxiety produced by the sound of their baby’s crying.) The mother’s task is to act as a container, tolerating without being overwhelmed by her baby’s feelings, thinking about them and then giving them back in a more bearable form. She digests how the baby is feeling, sometimes consciously but probably more often without being aware of doing so. She becomes a thinker for the baby’s thoughts. For example, if her baby cries furiously when being undressed, the mother may touch or pick up her baby, or hold the baby with her voice saying soothingly something like ‘You don’t like being all bare do you, but you are quite safe and I’ll soon have you dressed’. Whether or not she puts it into words like these, the mother conveys her own good feelings and the infant takes in (or introjects) ‘the feeling of "being contained", of maternal space having been available for their anxieties to be tolerated and thought about’ (Copley and Forryan 1987/1997: 241). By receiving more loving than hating feelings the baby begins to bear and manage their own angry and anxious feelings, and no longer has to get rid of them by projecting them into someone else. When this happens the baby internalizes not only the experience of being contained but develops a mind able to hold thoughts.

A literal example of this containing process takes place when a mother is feeding her baby; there are parallels between physical and emotional digestion. The mother matches her pace to the baby’s appetite and interest. If she feeds too quickly the baby feels force fed and turns their head away – it’s just ‘too much to swallow’ or ‘needs time to digest’. Or maybe there is not enough and the baby is left feeling ‘empty’. We use these expressions to describe our feelings too. What we hope for is ‘something we can get our teeth into’, even ‘a feast’ of ideas, providing ‘food for thought’.

The experience of emotional holding or containment enables the baby in turn to become a container of feelings, able to hold on to them and think about them, a process later helped by putting them into words. Stern (1985) describes this process as the child’s initial emergent self developing into a core self (by about six months), and then becoming a more self-aware subjective self, which with the development of language becomes a verbal self too. This achievement of a verbal subjective self, of ‘reflective self-function’, is the key to a child’s resilience in adversity (Fonagy et al. 1994). Winnicott calls this stage ego integration, the development of an integrated self. Such a child has reached the age of concern, Klein’s depressive position. This does not mean that the child is depressed but that they are able to experience pain and sadness, guilt and grief, that is, concern for others and the beginnings of empathy. So from experiences in their first relationships the baby develops an inner working model of the world as trustworthy (Erikson’s 1965 ‘basic trust’) and of themself as loving and worthy of love. This is the securely attached child (Bowlby 1988) who, paradoxically, is confident to explore and learn, knowing that there is a secure base to return to if things get out of hand.

Children with Damaged Attachments

The consequences of impaired emotional containment

We know that babies thrive on sensitive and ...