![]()

Part One

Definitions and purpose

![]()

01

The key account approach

Key Account Management (KAM) requires rules, but this is not a rule book. What follows will describe the concept, suggest a range of useful tools, and lay out the many choices you will face, illustrated by examples, but the rules are down to you.

It is to be hoped that you regard this as a good thing. Those seeking ‘off-the-peg’ solutions for their key accounts are not taking the task seriously.

There is, however, one golden and universal rule (and one that confirms the danger of the off-the-peg solution), and that is:

the precise form and nature of any KAM application must depend first and foremost on the nature of the customer.

KAM was born and raised in the world of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sold through large-scale multiple outlet retailers, but an application that will suit the likes of Tesco, Carrefour, or Walmart is unlikely to match the needs of a supplier in a B2B (business-to-business) environment, still less that of a healthcare or financial services provider. Selling to a bank, or a hospital, or a manufacturing company is very different from selling to a grocery retailer.

CASE STUDY Breaking the golden rule!

Many pharmaceutical companies have come only recently to the realization that KAM might be for them, and in their haste to ‘catch up’ they looked across their own business for examples of existing good practice. Those that had an ‘over the counter’ part to their business (that is, they had products that could be sold direct to the patient by retailers) found that they already had experience of KAM in that retail environment, and in some cases sought to apply the rules learned there to their other business areas, whether selling to General Practitioners in Primary Care or to the more specialist areas that involve working with the complex networks of influencers in and around hospitals. The results hardly need mentioning, and the lessons were quickly learned.

As well as the nature of the customer, there is the nature of your customer portfolio to consider.

For some, there might be four or five customers that represent the lion’s share of the sales revenue. In such cases it may seem clear which customers represent the key accounts, and why they are important; losing such a customer from the portfolio will be a very painful experience. But be careful not to take this focus on size unthinkingly: what if you lose money in working with one of those big accounts – would you still regard it as key? Or what if, by knowing their size and importance to you, they are able to bully you beyond the point that is good for your health? Is this still a key account?

For others, the customer base might be much broader and flatter, with no customers standing out as significantly bigger than others. A pharmaceutical company selling to hospitals may have such a portfolio. Who are the key accounts in such a circumstance, and why? Perhaps the key accounts are those that, while small today, will be big in the future, and represent the greatest opportunity for future growth. A rather different (and more ambitious) answer may be that if it is possible to work very closely with a small number of these customers, so as to learn from them, and then apply that learning for the benefit of all customers, then these KAs are important as ‘learning’ accounts: a very valuable category.

Another business may have some customers that are simply more complex than the rest, and the nature of these customers calls for a different kind of approach. In this instance an important question is raised: are those customers called key accounts more important than the rest, or are they just different?

It becomes clear already why only you can set the rules, but whether your customer portfolio demonstrates the 80:20 rule or not, there is one piece of advice that has to come right up front: don’t try practising KAM with too many customers. It is far better to be brilliant with a few than mediocre with many, or to put it more bluntly, plain poor with too many.

CASE STUDY Too many key accounts means no key accounts

I always recall the phone call from a new client who in answer to my question: ‘How many key accounts do you have?’, responded smartly with the answer: ‘Seventy-five’. OK, there are no rules other than the ones you make for yourself, but I have yet to meet a company that can honestly convince me that they can manage 75 key accounts. Worse was to follow, as when I asked how many key account managers there were in the company, the answer was (and I hope I don’t make anyone feel too bad about this): ‘Three’. That’s 25 each, which is plain absurd, not to say impossible. In truth, this client had no key accounts – how could they when they aimed to spread their resources so thinly? I asked a few more questions: ‘How did that label “key account” help them in allocating resources, time, and money?’ It didn’t. ‘How did they behave differently with those 75 customers compared with all the others?’ They weren’t sure that they did. ‘How did those 75 customers see their own business enhanced as a result of this label?’ It was this last question that exposed the true problem: my new client’s customers were telling them that they didn’t see any advantage to them in this ‘special’ relationship…

I can’t tell you how many key accounts you should have, but I do know that most people start the journey with ambitions that end up being cut in half, and then some, once the realities set in. The total of the fingers of two hands is not a bad top limit in most cases.

CASE STUDY

One of the best applications of a KAM strategy with which I have been involved was by a healthcare supplier in the USA, a company called Nutricia, but it all began with something of a worry. From a list of many hundreds of customers they had identified some 40-plus as key accounts. It was a list that was slowing them down. On realizing that it was OK to have just a handful of KAs, particularly if some of them were seen as ‘learning’ accounts, and then another handful of ‘potential’ KAs, the brakes were off and the route to KAM Excellence was made clear.

Important or different?

While for most of us our key accounts will also be our most important customers, this is not a universal truth. The business that views its key accounts as the ones that, while small today, represent the brightest future, might rightly regard today’s large customers (the ones that pay the bills and keep the factory running) as more important: perhaps it is a matter of timescales. Whether most important or not, the key accounts will certainly require a different approach to the rest, and will bring different rewards. If that is not the case then there is little point in classifying them as key, and even less point aiming to practise Key Account Management.

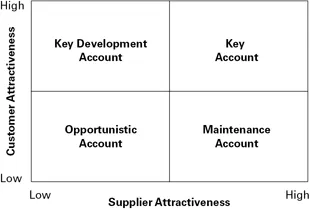

The recognition that certain customers are sufficiently different to warrant a specific type of attention is what lies at the heart of what we might call the Key Account Approach. Customers are classified based on their mutual attractiveness, that is, not only how attractive they are to you, but also how attractive you are to them. Figure 1.1 suggests four classes of customer that might result from this kind of classification. The methodology behind the process that we call Customer Classification is described in detail in Chapter 26.

Figure 1.1 Customer classification

Those customers in the upper two boxes are not necessarily designated as being more important, but they are certainly different, and require a different approach, as do those in the bottom two boxes. This is what we call Customer Distinction and the process involved will be described in full in Chapter 27.

Taking these four classes of customers, resources are then applied based on the potential return on investment from each class. Such ‘differential resourcing’ strategies are vital to the success of KAM. This is a good deal more than a labelling exercise: some customers deserve more time, more people and more investment, and some deserve less, but they all deserve the right level for their status in your portfolio.

CASE STUDY Making the rules to suit your circumstances

One of my clients has a customer portfolio of remarkable flatness. They sell to hospitals and it would seem that their overall national market share is replicated pretty uniformly in each individual hospital. Ranked by their own sales volume their customer list replicates the ranking of hospital size measured in patient numbers. This is not an unusual scenario in healthcare markets. They are, however, very keen on the idea of key accounts, seeing them as those customers from which they have the most to learn – perhaps because they represent the leading edge of treatment practice – and also those customers that will help them most in influencing others – perhaps because they are staffed by key opinion leaders.

I was very impressed by their attitude towards the classification process, and its outcome. First, they put a lot of effort into agreeing the criteria for attractiveness and then ranking the customers accordingly. The result was encouraging; a small number of customers in the top right (a manageable number) and a healthy number top left (from which to select top priority targets). But when they added up the volume and...