- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by a noted illustrator and teacher, this guide introduces the basics of line drawing. British artist Edmund J. Sullivan, who merges the traditional nineteenth-century style of illustration with elements of Art Nouveau, begins by introducing readers to the freehand drawing of abstract lines and advances to the freehand drawing of natural forms, consisting mainly of plane surfaces or single lines.

Subsequent chapters illustrate and discuss representations of the third and fourth dimensions, the picture plane, formal perspective, and the drawing of solid objects, including their depiction in shade and shadow, and their modelling. Additional topics include shadows, reflections, and aerial perspective as well as figure drawing.

Subsequent chapters illustrate and discuss representations of the third and fourth dimensions, the picture plane, formal perspective, and the drawing of solid objects, including their depiction in shade and shadow, and their modelling. Additional topics include shadows, reflections, and aerial perspective as well as figure drawing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

XIV

BEAUTY

So far as we are concerned in what is called the creation of any work, all that can be said is that Beauty consists in exactitude of application to purpose, which will imply the greatest economy of force to a given end.

A square peg in a round hole is the antithesis of Beauty.

The definition of dirt as “matter in the wrong place” is admirable.

The quality of squareness in a peg is not in itself admirable, nor, on the other hand, is roundness. Of two pegs, one perfectly round, the other perfectly square, what is there to choose, all other things being equal? Each implies a purpose or design, so that neither is beautiful unless it fulfils the condition laid down in the purpose—to fit.

An unrelated quality as smoothness, yellowness, coolness, dryness, brightness, has not in itself Beauty. The quality must be appropriate.

It cannot be said that a cube is more beautiful than a sphere, except it be better adapted to its end, otherwise our lovers might be sighing in the rays of a cubical moon.

A billiard ball is a beautiful billiard ball according to its capacity for accurate rolling, which is in exact accordance with its sphericity—its singleness or impartiality of surface; a die is beautiful in accordance with its exact partiality into six surfaces, so that there may be no doubt as to which side lies uppermost. While in both die and billiard ball exactitude of balance is called for, a bias is put upon bowls. Gilbert’s fancy of a “cloth untrue with a twisted cue and elliptical billiard balls” as a punishment to fit the crime of the billiard sharp, and Lewis Carroll’s flamingo’s neck as a croquet mallet, have the beauty that belongs to the purpose of stirring our risible faculties by tickling our sense of the incongruity of the instrument with purpose—an unexplainable “cussedness,” a kink in things that mars the perfect order.

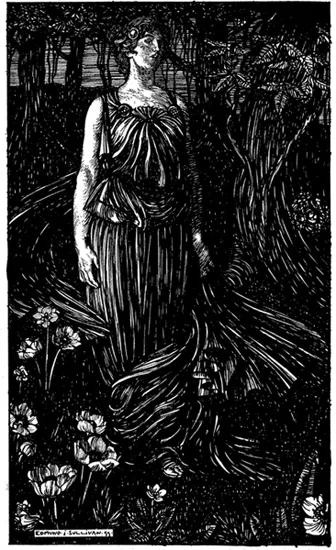

FROM “A DREAM OF FAIR WOMEN”

An attempt to combine severity of line with richness of modeling and colour. In the dark passages the white spaces become more important than the black lines which include them.

The crux comes when we begin to consider those things either inside or outside ourselves where the purpose is obscure or entirely beyond out comprehension, which yet excite pleasure in the contemplative mind.

What is to be said of those beauties that exist without purpose, so far, that is, as we can see or realize the purpose; as in a sunset, a rose, or a butterfly ?—all these appearing to squander a quite unnecessary loveliness out of proportion to any useful purpose so far as the materialist can see.

What are these but ornament without economy ? Does the flower of the rose contain more beauty than its thorn, the placid sunset more beauty than the thunderstorm, or the butterfly more than the worm, since each equally serves a purpose, and the purpose served being frequently more readily appreciable in accordance with the obviousness of the purpose ?

We must reckon here, I think, with the purposes of our own life, and the beauty implanted in our own minds. This may sound like begging the question, but we must admit mystery here. “Not every height is holiness, nor every sweetness good.”

A child with the most limited range of association will love bright colour for its own sake, and will prefer the pink part of the blanc-mange to the white, though there be no appreciable difference in flavour. Hereditary instinct will not guard it against yew berries or deadly nightshade, and horses and cattle are frequently poisoned by the yew, apparently by a wanton malice on the part of Nature. Offensiveness of this kind, so far from proving protective, might well have led to the entire extinction of the yew and of nightshade, by leading to a vendetta against the offender.

We love roses for the unexplained pleasure which they yield to the senses of scent and sight, apart from any obvious purposes they may serve other than these gratifications ; we rear them, not for propagation of their own kind, but for our own gratification, to the extent that we perfect the regularity of their form, and the delicacy of their scent and colour; we assist in the recreation of loveliness ; but what is it primarily that impels us to appreciate the original flower in its form, colour and scent—since the wild rose apparently served little other end than its own will to live ? and in what does that differ from the nettle ?

The purpose of creation of a work may be ugly, yet what more beautiful objects have been wrought by man than his perfected weapons of destruction, from the sword and the stiletto to the rifle and the man-o’-war ?

Balance, sharpness, line and appropriate ornament, either for deadliness or display, in the blade, the hilt and the scabbard, these are examples of fitness for purpose.

As to mankind itself, it is beautiful in proportion to its economical adaptation to the purpose of its own being. To put sand in the wheels of the social machine is an ugly act, no matter how profitable it may appear for the moment to the individual. Being anti-social he will be destroyed as soon as society can lay hands upon him, so that his: destruction is to all intents and purposes suicide, as surely as a murderer who is hanged may be said to have destroyed himself as well as another. This is uneconomical, a waste of two lives, good and bad together—altogether an ugly business.

All waste is ugly.

The best use is economy; so that we come to this, that utility and beauty are allied. Cutting blocks with razors is a waste of razors, it is inappropriate—therefore ugly.

The most useful of its kind will be the most beautiful of its kind.

The highly specialized for a particular purpose, though to some extent incapacitated for general use, will have a highly specialized beauty; as a shire horse for slow strength, and a thoroughbred for speed, or a bull-dog for tenacity and a greyhound for swiftness.

Their relative beauty will depend upon the relative value set upon these qualities; so that as these qualities may be more or less in demand at different times, so will their beauty or otherwise vary in the minds of men.

It is possible that the general agreement upon the so-called “classic” type of beauty arises from the small degree of specialization for any particular purpose—the small amount of raciality involved, let us say, in the Venus de Milo, so that, except for the dignity and grandeur with which the sculptor has invested her, she may be said to contain all the possibilities of, and therefore to represent, all women to all men rather than any particular individual or characteristic.

Such a summary presentation is only to be achieved by great knowledge; and to attempt such, as so many artists do, without that knowledge, by a simple repetition of type, is to run upon failure. The safe way is to aim at a full appreciation and selective presentation of character as the artist himself sees and feels it, not squeezing an arbitrary mould upon the living character, and suppressing its variations, but accepting, and even emphasizing, whatever deviation may appear from the normal.

Here is an indication of two attitudes or two conceptions of Beauty—one that shall “blend, transcend them all,” by presenting to our view a bouquet of all the flowers, carefully cultivated without thorns or weeds; and another that shall not only recognize but display with a nicely proportioned emphasis one individual flower at a time, not only in what to a superficial view is its perfection alone, but even the defects of its qualities, which to a large mind and a deep-seeing eye are part of its true perfection, just as a day contains darkness as well as light.

Portraiture of individuals comes within the latter category, and the beauty of a portrait will reside rather in its specialization of character than in its conformity with a conventional type.

The purpose of a work of art will dictate which point of view the artist should adopt—whether stress should be laid upon the type or upon the individual.

A picture of a drawing-room scene of to-day in which attempt should be made to represent all the women according to a single type of Venus, and all the men as Adonis, would fail in the dignity aimed at, since it would fall into pomposity and absurdity by reason of its palpable untruth to familiar facts.

All may be well, but there can be, in an imperfect world, but one best. That there may be many kinds of goodness and so many varieties of “best” is a blessing.

Just as “dirt is matter in the wrong place,” so there can be no pleasure derived from Beauty misapplied. Here again is lack of economy. For the rough work of the world rough tools and means are requisite.

It is distressing to see a sculptor impatiently polishing the marble before he has finished with the punch and chisel. Such a work can never be finished because it has not been properly begun. In a drawing, if pattern, no matter how beautiful in itself, be applied to a weak construction in order to conceal its weakness, or, worse still, to take its place, nothing but irritation can be the result for any but shallow minds. Construction must take precedence of pattern or ornament, and only ignorance or vulgarity can hold otherwise.

A jug that will not pour, or a table that will not stand steady because in either case considerations of ornament have preceded considerations of the purpose of the thing designed, is an ugly jug or an ugly table.

Armour loses its beauty as soon as its protective value is lost sight of, or replaced by its decorative value, so that it becomes an encumbrance. The sons of King Gama in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Princess Ida, inæsthetic as they imagined themselves, and contemptuous of such matters, were acting in accordance with the canons of taste when they preferred to fight in shirt-sleeves. The armourer had become a poor artist, and it is to be supposed that a Cockney youth, who could manage with a length of his washerwoman mother’s clothes-line to trip up the most gallant knight, could have him at his mercy though he himself were armed with no better weapons than the coke-hammer and the bread-knife. Here is a reduction to the absurd, which Beauty cannot be.

Meanwhile the beauty of roses troubles us.

Is it roses, or is it ourselves, that more demands explanation is this particular ?

Where is the economy of a sunset or a rose ? Or is it in us that economy is being exercised ? And that having a mental hunger food is provided for it ?

What is the purpose of a rose in its relation to us, or of us in relation to a rose, that we should become excited over their presence before our eyes or in our memory ?

Why do we compare a rose favourably with other well-loved flowers ? Besides, there are many varieties of roses, each more beautiful than the other; one we admire for its size, another for its smallness; one for its redness, another for its whiteness; one because it is nearly black, another that its pallor is hardly flushed; one for its doubleness, another for its open singleness and simplicity. What is here but flat contradictoriness in such reasons as we assign to our appreciation of them ? Nor do we question them as to the purpose of their existence, nor demand the least explanation from them as to how they are justified by anything but their beauty, or, what comes to the same thing (does it?—or doesn’t it?), the beauty we find in them. Does the beauty of roses exist in roses themselves or in our love of them? Is it roses we love, or the gratification they give us ?

Tennyson’s “Day Dream” comes to mind here :

“So, Lady Flora, take my lay,

And if you find no moral there,

Go, look in any glass and say,

What moral is in being fair.

Oh, to what uses shall we put

The wildweed-flower that simply blows ?

And is there any moral shut

Within the bosom of the rose ?”

It is one of the questions that will tease humanity to the end—riddles which we cannot answer, and yet must go on eternally seeking to find out. If we could solve the mystery, would Beauty remain?

“LADY FLORA”

An attempt to achieve richness without sacrifice of the underlying severity of line, which is very heavy in order to support the superposed “colour.”

Certain abstractions such as Unity, and Variety in Unity, Harmony, Proportion and the like are put forward as essential qualities of Beauty, but each of these may be as hard to define as Beauty itself.

It would be necessary to examine the bases of sensation themselves to arrive at any satisfactory solution of only the first of the many facets to the question, “What is Beauty?”

In the case of sight with which we are immediately concerned, association alone is not sufficient guide. Red in its many degrees may be associated with sunset, with apples, with deadly nightshade and with blood; with food, with contentment and rest, with poison, with horror; with good and bad equally. If this is the case, association of ideas alone is not enough to account for our appreciation of colour; and if of colour, why not in other matters also ? That association is not necessarily the basis of our pleasure in colour may readily be proved by deciding whether we prefer the appearance of the red or the green railway signal against the night sky. The general choice will probably be the red, in spite of its being well known to all as the danger signal.

Colour will appeal to the sense more than to the mind, being an attribute of form; but form that does not appeal to the reason, and so offends it, either on account of its chaotic condition, its ineptitude for purpose, cannot please a fastidious mind. The mind demands construction and purpose in form, and unless this demand is met, not only is the mind not satisfied, but is actively dissatisfied and resentment is set up.

Discoloration, as being inappropriate to the object coloured, will also stir resentment in the same way, though the colour may not in itself be unlovely. Green or yellow cheeks, for instance, a jaundiced or cadaverous complexion, just as an excess of red, may be definitely unpleasant to the mind. But “discoloration” involves an association of ideas; in the given case of green cheeks implying an unhealthy state of body or an affectation suggestive of vicious taste, as opposed to pink as implying health and naturalness. The same shade that would be unpleasant upon a cheek may in itself give pleasure in a scheme of decoration for a wall or a china vase, where no particular thing is represented or even suggested, so that the association of ideas is, if present at all, so vague and remote that it may be dismissed as the basis of our sensation of pleasure. A vivid green or yellow reflection upon a face as apart from the local colour may, on the other hand, give exquisite pleasure, and that of the most innocent order, as from the bright green reflections of sunlit grass, or of yellow, as when children test each other for “...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Contents

- I. Introductory

- II. Drawing Materials

- III. Abstract Straight Lines, Angles and Curves

- III. (Continued) Freehand Drawing of Abstract Lines

- IV. Freehand Drawing of Natural Forms, consisting mainly of Plane Surfaces or Single Lines

- V. The Third and Fourth Dimensions

- VI. The Picture Plane

- VII. Formal Perspective

- VIII. Drawing of Solid Objects

- IX. Solid Objects in Shade and Shadow

- X. Modelling of Solid Objects

- XI. Expression of Solids in Relation to one another—Aerial Perspective

- XII. Shadows, Reflections and Aerial Perspective

- XIII. Figure Drawing

- XIV. Beauty

- XV. Conclusion in Plaster

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Line by Edmund J. Sullivan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Theory & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.