- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On the Art of Drawing

About this book

With this helpful and informative guide, a leading American illustrator offers insights into how serious beginners can become sketch masters. It combines a focus on the nature and importance of technique with practical suggestions for developing drawing skills with a variety of tools, including felt pen, pencil, crayon, brush and ink, charcoal, casein, tempera, and wash.

Norman Rockwell praised this book as "a real contribution not only to illustration, but to art." Rockwell and author Robert Fawcett were founding faculty members of the Famous Artists School, a correspondence course that has coached legions of professionals and amateurs. Known as the "Illustrator's Illustrator," Fawcett stresses design and composition in his analysis of 100 illustrations of landscapes and human figures. His realistic depictions convey solid fundamentals of drawing that every artist, illustrator, student, and hobbyist needs to know.

Norman Rockwell praised this book as "a real contribution not only to illustration, but to art." Rockwell and author Robert Fawcett were founding faculty members of the Famous Artists School, a correspondence course that has coached legions of professionals and amateurs. Known as the "Illustrator's Illustrator," Fawcett stresses design and composition in his analysis of 100 illustrations of landscapes and human figures. His realistic depictions convey solid fundamentals of drawing that every artist, illustrator, student, and hobbyist needs to know.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On the Art of Drawing by Robert Fawcett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

The Why of Drawing

The word drawing seems to be one that all professionals and students use freely, but which no two ever seem to use in quite the same way. It is obvious that a new book on the subject, in a field already crowded, must consist of more than a collection of plates demonstrating the author’s versatility. It must also be more than a collection of fine drawings of the past and present, for though the study of these is almost mandatory, the books of reproductions are many and, without demonstration, too many fail to see the pencil and chalk studies of the old masters as applicable to their present-day problems. They end by paying lip-service to excellence without delving further into it. Furthermore, the trends of contemporary painting seem to by-pass draftsmanship as a means. The fact that a nonrealist or semirealist like Picasso started by drawing in a way which resembled Ingres is laid by some to the inexperience of youth. Actually Picasso to this day starts with careful, rather realistic drawings, which he later overpaints and “destroys” in his own word, as his study of his subject deepens and progresses.

The reliance by many painters and most illustrators today on the photograph as a substitute for drawing shows a lack of understanding of what the ability to draw means. These two have nothing to do with each other. They are not in conflict because there is no similarity of purpose. It will be one aim of this book to show that the study of drawing can be a release to the imagination and not, as photography sometimes is, simply a realistic documentary aid.

If parts of this book seem to stress constant and what might be called relentless drawing it is only because it seems time today for an application and devotion which the student may up to now have congratulated himself on having dodged. I know of no way to avoid this completely if the desire is to become a draftsman in the sense of building a confidence that nothing visible or imagined is beyond one’s ability to record on paper. This, it seems to me, is the ideal to be attained. And what holds the imagination back more than anything else is sloppy seeing. We must see first, then we may safely imagine more; vagueness and blurred seeing are not the same as inspired transformation of reality.

Sir Joshua Reynolds in his address to the Royal Academy students in 1769, told them this, “The error... is that the students never draw exactly from the living models which they have before them. It is not indeed their intention; nor are they directed to do it. Their drawings resemble the model only in the attitude. They change the form according to their vague and uncertain ideas of beauty and make a drawing rather of what they think the figure ought to be than of what it appears. I have thought this the obstacle that has stopped the progress of many young men of real genius; and I very much doubt whether a habit of drawing what we see will not give a proportionable power of drawing correctly what we imagine.” (Italics mine)

There are those who contend that this kind of study is outmoded today, that the modern artist develops somehow by himself and without formal training. It is suggested that the development of the student’s intuitive perception is gravely retarded by what are sometimes referred to as the “clichés” of seeing. The vague and indefinite scribbles of the beginner are too often hailed as rare flashes of insight which will forever be denied the patient searcher. The ability to draw well, we are told, is something to be unlearned.

It would be a matter of concern if this were true, but it is not. The keen eye which looks in wonder and appreciation at how things are, soon develops that humility which precedes the gaining of knowledge.

The reader may notice some seeming inconsistencies as this volume progresses. They are perhaps not really so. The reason for this is that what is right and useful advice for a beginner is not necessarily so later for a more mature artist with some experience, and I have tried to keep the study of drawing in some sort of logical sequence. If one is still mildly confused by these occasional contradictions, then the happy time may have arrived for him to make up his own mind, and eventually to put all books like the present one into the discard and strike out on his own.

I occasionally experienced a similar difficulty in making some of the drawings which illustrate this volume, in trying to draw in a manner which is no longer natural to me, but which was the best I could remember doing as a student.

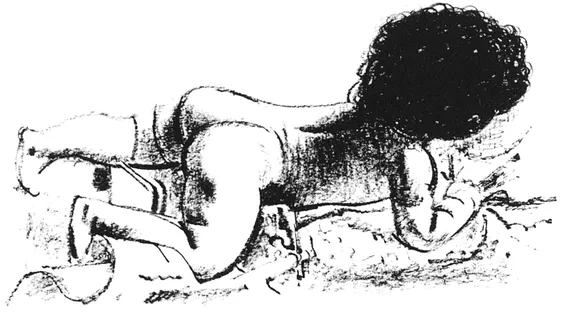

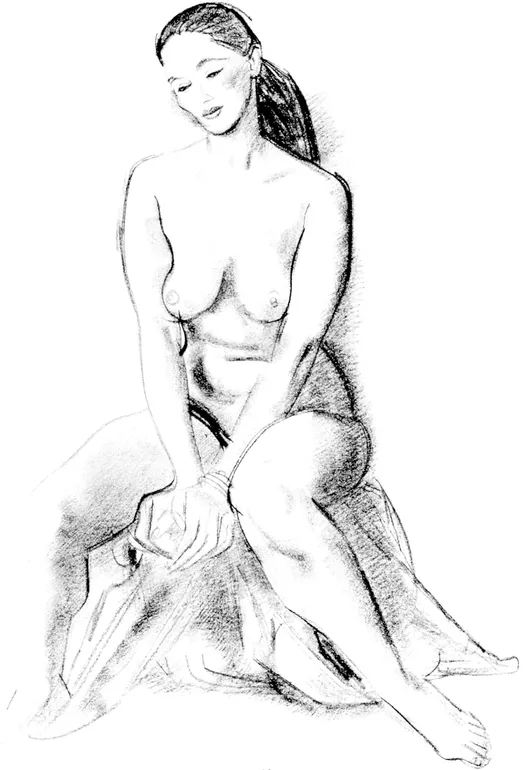

Learning to draw is more than learning to draw the human figure — theoretically one could become an excellent draftsman after years of drawing only eggs or apples. Yet many demonstrations in this volume are from the figure, and in making them I have accepted the convention of the life class and the nude as a point of departure.

The study of anatomy is purposely ignored. I seem to remember studying anatomical diagrams as a student; I even attended medical school and watched dissections for a short period. In urging now that the student leave anatomy to the surgeon, I mean only that it should not become the substitute for the penetrating and discerning eye. The study of anatomy will in any case be forgotten by the developing draftsman as soon as the more exciting aspects of drawing begin to manifest themselves to him. Anatomy should be dropped when it starts to interfere with that new, fresh look, that deeper insight and understanding which are the hallmark of the draftsman. Our instrument is the eye, not the scalpel.

The same, I think, is true of perspective. You may study this subject until the glad day when your picture, which you know is correct in terms of that science, begins to look incorrect and dull to your knowing eye. The time has then come to discard perspective and rely upon the trained senses, one of the uses of which is to reveal the truth in what may seem superficially untrue. As a matter of fact, we are always dealing with illusion so that the question of “right” or “wrong” should not enter our discussion.

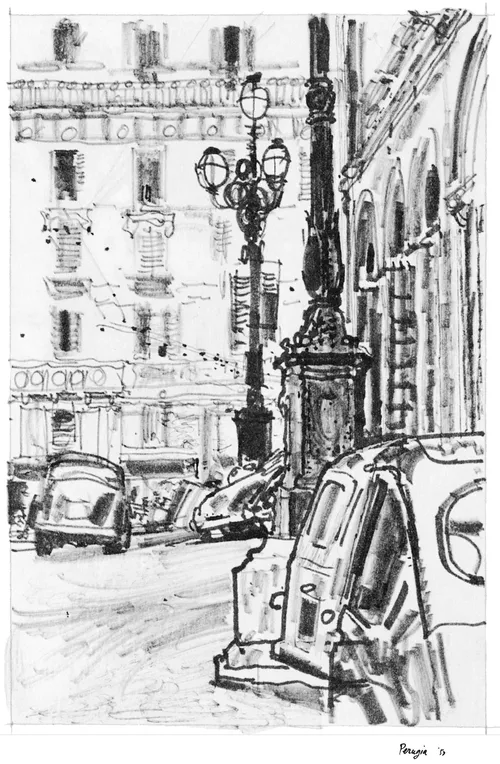

It is possible to divide the subject of drawing into two broad classifications. The first is drawing as preparation for something else, for paintings, for more complete realization of plastic ideas. These are studies. The second is drawing as an end in itself, as a complete art form. The former will be more diagrammatic; it is the kind of drawing which I think can be demonstrated. The second is more difficult to define, for there are no limits to the fancy or to the imagination. The appeal of this kind of drawing is aesthetic, and the response should be pure, uncritical pleasure. It cannot be taught. It is complete and final and subscribes to no rules. For this reason we will not be concerned with it, except to be cautiously aware that it can refute every word ever written on the subject.

A Chinese epigrammatic poem contains the line “He who values a picture for its resemblance, has the critical faculty near to that of a child.” The Chinese knew of that higher form of aesthetic pleasure than the mere recognition of facts. However, the writer goes on to say “Art produces something beyond the form of things, though its importance lies in preserving the form of things.” Mr. Bernard Meninsky, draftsman and teacher, sees in “this seeming paradox the key to the mystery — the great draftsman preserves a form whilst endowing it with a sense of infinity.”

But while a good drawing is an informal revelation of the artist’s basic vision, a textbook like this must limit itself to what is demonstrable; that is, the artist’s outer vision, the simple acts of seeing, understanding, and recording. I own one volume on this subject by an excellent artist, illustrated with particularly good examples of his fine, sophisticated drawings. But he is a mature artist; the drawings contain much that is imaginary and inventive. The student could easily be baffled when confronted by these examples because he cannot see the same things in the model. If his admiration for the artist’s style is great he may be tempted to imitate the surface mannerisms, and the result will be an affectation. That is why many of the illustrations in this present volume are as diagrammatic as possible, as close as possible to what the normal eye sees.

For our purpose it would seem best that we think of our job only as the development of an aptitude, otherwise we are soon going to be out of our depth. In the end it will be only by arbitrary limitation that we can confine it to that. But we shall try to remain in the realm of things demonstrable. We should, in fact, be able to prove what we say and avoid merely voicing preferences.

To become a professional requires training. Training begins in the simplest way; that is, by learning to draw. To some, drawing is looked upon as a necessary evil. It should be pure pleasure instead. Training does impose a discipline, as does any schooling, but that is no reason why it should become a dull routine. To train one of the senses should be a joy, even if it involves a certain amount of repetition.

It would, of course, have been nice to confine this discussion to pure drawing, without reference to how the aptitude will be used. But it is useless to deny that many students of art begin by preparing themselves for a particular field. Insofar as they do this it seems to me they limit their own potential, but since it is the case we might explore the reasons for it.

High on the list of the applied arts is so-called graphic art, illustration in particular. For this reason I have included at the end a section on the application of drawing directed specifically to the illustrator, for good illustration demands a particularly high degree of draftsmanship. But during the argument we will try not to single out the illustrator for special consideration. Suffice it to say that it is impossible for him to draw too well. If a student illustrator fears that he is on the way to achieving a greater aptitude than he will ever need to employ, he is almost certainly wrong. As we have said, greater knowledge will result in a better illustrator (though, perhaps, under commercial conditions, not necessarily a happier one). His drawings are not likely to display dazzling feats of draftsmanship. They are much more likely to be characterized by the restraint of self-confidence. The artist who has resources does not need to announce this fact from the housetops — it will be apparent.

Later if he feels that the restrictions of illustration limit his expression he will either call upon his greater knowledge to enrich and prolong his development and career, or else he will take time for self-exploration. In either case he cannot lose, and he should therefore approach drawing as an art form in itself, as should all who love the medium.

We said that good drawing deals with understanding. Understanding of drawing is best brought about by absorption, by constantly looking at other drawings. By studying, appraising, and analyzing, one develops a set of standards which begin to satisfy and enrich the experience. Of course, this is not inevitably the case. I think it was Whistler who once said, “a life spent among pictures does not necessarily produce a painter; otherwise the policeman at the National Gallery might begin asserting himself.” The policeman in question inevitably looked over the pictures, but not at or into them. (Neither, in fact did most of the visitors to the gallery it was his job to guard.) But the fact that the experience of most gallery visitors is superficial does not mean it should continue. We grow in understanding as naive standards give way to more sophisticated ones. These steps in growth are too often accompanied by a complete rejection of that which only yesterday commanded our admiration. A more mature step occurs when we return in retrospect and see both in truer perspective.

The violent likes and dislikes of youth, especially of the art student, are typical. Later, one never again has the temerity to accept or condemn with such vehemence. The trouble is that without experience, superficial efforts are often considered important, and technique is often confused with content. Yet I doubt whether this can be avoided just by reading on the subject. Drawings are too often categorized as academic or modern, serious or superficial, fine or commercial, whereas the only standard worthwhile is whether they have meaning for the individual, and what kind of meaning it is. One would have thought that the recent elevation of Daumier, the prize cartoonist of his day, to the ranks of the great artists might make some of us pause before the too ready evaluation, but it rarely happens. In New York City art on Fifth Avenue is ‘fine’; that of Madison and Lexington Avenues is ‘commercial,’ and having neatly pigeon-holed the distinction, we no longer feel the need to give it any further thought.

I suppose the plea I am making here is for the open mind, for the courage to hold values and express opinions which may not be the popular ones. Also it is possible for worthwhile drawings to appear at unlikely times and places. Without an open and therefore receptive mind one will not recognize them when they do.

The English painter Walter Sickert, friend and contemporary of Manet, Degas, and Whistler, once said, “If we allow ourselves to ask who was the greatest English artist of the nineteenth century it would be difficult to find a candidate to set against Charles Keene, a draftsman on a three-penny paper.” Unfortunately Charles Keene was dead for many years before this opinion became the accepted one.

Why do we draw? We draw, I suppose, because it is one of the most primitive and natural human instincts. Some thousands of years ago we would have drawn on cave walls records of the animals which the more virile members of the tribe had stalked. There is hardly a child today who, before the age of reason, does not reach out for the colored crayons to record his first visual impressions, and later his first imaginings. And drawing should come as naturally as that.

When we ask a question of the scientist, in all probability his answer will be a mathematical equation. But ask a technical question of the average artisan — a plumber or a carpenter — and out will come that blunt stub of pencil, and the tortured attempt to make clear to us in diagram a point which it would be impractical, if not impossible, to put into words. The artist and student should approach drawing with the same kind of determination.

We can become bored by a verbal description of a landscape, whereas a drawing or painting of the same subject might charm us. A description of a figure would quickly exhaust the average vocabulary, but a drawing informs us immediately. We are inclined to pass rapidly over the novelist’s description of the physical properties of his characters, whereas the illustrator’s picture is designed to entice the reader into the story.

When I draw a figure I do so to make an ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1. - The Why of Drawing

- 2. - Drawing for Information

- 3. - Questions and Answers

- 4. - Drawing Naturally

- 5. - On Technique

- 6. - Variety of Drawing

- 7. - Drawing as Understanding

- 8. - Round or Flat

- 9. - From Light to the Scene

- 10. - Taste

- 11. - Seeing and the Medium

- 12. - Economy

- Illustration — The Contrived Picture

- Dover Books on Art and Art History