eBook - ePub

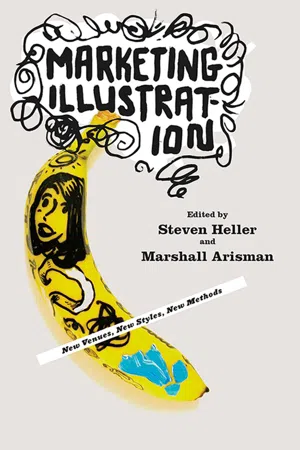

Marketing Illustration

New Venues, New Styles, New Methods

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The market for illustration is changing. How can illustrators survive and thrive? Illustration students, educators, and working artists will find illuminating commentary on editorial, graphic novels, comics, animations, Web, games, toys, fashion, textiles, and more, along with an exploration of how old platforms have changed and new ones emerged. Fifty working illustrators, including such top names as Christoph Niemann, Alex Murawski, Jashar Awan, Yuko Shimuzo, and Tomer Hanuka, share insights on what works now. Published in association with the School of Visual Arts, Marketing Illustration explores the impact of technology and the future of the illustration market. No illustrator can afford to miss this thought-provoking resource.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marketing Illustration by Marshall Arisman, Steven Heller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Design History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

What to Do If You Want to Make Art,

But Need to Make A Living

Throughout the twentieth century, the obvious solution to this particular quandary was to compromise by becoming an illustrator (or a designer). It is an accepted myth (even in most art schools) that real artists do not make money, but through accepting illustration into one’s life comes the potential to earn a reasonable living while continuing to make art (or a reasonable substitute for art). Well, that paradigm has changed over the past dozen years. Art increasingly intersects with commerce, and artists have found that their muse-driven concepts can, under the right circumstances, be transformed into marketable products.

Likewise, illustrators have found that certain styles and conceptual trends are currently accepted as art in the hollowed halls of galleries, museums, and art fairs (like Art Basel). As sacrosanct distinctions are routinely challenged and with the boundaries between fine and applied arts becoming increasingly fungible, making a living (or at least somehow profiting) from art is not as difficult as it once was.

Of course, not all fine artists have the entrepreneurial gene, and not all illustrators are perfectly suited to perform in the art world, but for those who can make the respective leaps on either side of the divide, a potentially vital and welcoming market awaits. For the artist, it is a way to reach more of an audience with an alternative kind of “multiple”; for the illustrator, it is a way to branch out from the conventional problem/solution model into more self-initiated projects. But this is not an either/or scenario. Illustrators are not required to become fine artists in order to expand their earning capabilities. In fact, the definitions of illustrator and of illustration are changing in such a way that editorial and advertising are no longer the only options. Illustrators are now able to show their work in art venues, just as more traditional artists are welcome in commercial venues.

The reason for this change is that, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, art has expanded to fill the many containers built with new technologies, economies, and moralities. Art is not restricted to canvas, clay, or paper and is as much a response to external media and mediums as it is to internal emotions. Moreover, the creative act is not determined by the ratio of suffering or angst to ultimate result, it is defined by the impulse to create something that has not existed before or build on something that has.

The consequence of this impulse is that artists and illustrators are currently creating “stuff.” Not only are the boundaries between fine and applied arts more or less lowered, but form, content, and accessibility are more democratic. In this way, the entrepreneurial spirit is ignited, and graphically, greater options are now available. Below are some of the ways illustrative image-making has become more entrepreneurial.

Toys

With the explosion in vinyl toy marketing and manufacture with companies like Kidrobot and Giant Robot, illustrators have a new venue for their more absurdist, three-dimensional concepts. What began a decade ago with a few artists transforming action hero toys into mutations has grown into a highly profitable collectible industry.

Games

To say video games are a mammoth industry is not an exaggeration. Billions are spent annually on both development and sales, and illustrators are increasingly employed in rendering and development. While it is not always easy to create characters from scratch, the video game field welcomes as much creative thinking as it can absorb.

Animation

The most significant change in field of illustration can be summed up with the word motion. While illustrators have worked in the animation field since the first animated cartoons in the early twentieth century, digital technology allows anyone with software skills to be a desktop animator. Motion has become as common to illustrators as cross-hatching, and animation is now second nature.

Novelties

Illustrators have long toyed with the idea of creating knick-knacks, and some have produced delightful novelties that end up being sold in design-centric boutiques. They range from silly to profound, and they can be pure designs or concept- or character-driven.

Candies

This may not be the most prodigious of the entrepreneurial ventures, but specialty companies like Blue Q in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, produce various confections packaged with silly but cleverly illustrated covers and labels. Some artists have used their packaging skills to create custom lines of candy, as well.

Books

This is not an unconventional alternative, but increasingly, illustrators are turning to writing, illustrating, producing, and packaging books—and’zines—that have independent life in the marketplace.

Graphic Novels

They are technically books, but graphic novels and artist books have a distinct genre of expression. Various specialty publishers, like Drawn and Quarterly and Fantagraphics, offer prodigious outputs of historical and original material, which increases the market for interesting new work.

Wallpaper

When it comes to products created by illustrators, the quirkier, the better; and few things are more unusual than wallpapers. While there is not an immense market for it, artists have, in recent years, become involved in wallpaper production, as well as designing wrapping paper and textiles.

Fashions

Speaking of textiles, designers have contributed their fair share to this field. But artists are increasingly developing all manner of clothing, from hats to shoes, and these days, hoodies.

T-shirts

A decade or so ago, when illustrators had an entrepreneurial inkling, their first thought was, Let’s create a T-shirt line. The artful (and often just plain goofy) T-shirt industry has grown exponentially. It is also a good jumping-off point for other street fashion concepts.

A word to the wise: Illustration is a stepping stone, not an end in itself. Working with images opens doors to the above—and doubtless many other—unheralded jobs and gen res. The key is to think entrepreneurially and to spread your talent as far as it will go.

The New Geppettos:

Illustrators as Toy Makers

The prodigious and financially lucrative trend in eccentric, alternative toy objects, started over a decade ago in Japan, and with Tsunami force, washed over the United States and Europe. The phenomenon seemed so genuinely novel (in a post-punk, new-wave techno sort of way) that in some circles, these toys have come to define a twenty-first-century pop-cultural zeitgeist. They have certainly become an expressive medium for the many artists and illustrators bereft of traditional editorial and advertising outlets, and they appear to be a logical off shoot of new-wave animation and graphic novels.

The current wave of artist toys made by poster artists, graphic designers, and comic book makers—including Frank Kozik, Geoff McFettridge, Gary Baseman, and Tim Biskup, among others—are pushing limits of a different sort. Their work, which appears in alternative mags like Juxtapoz, is a fervent return to what might best be described as a consuming passion. Unlike their modernist forebears, the new toy producers are less concerned with making one-offs than they are with producing collectibles designed to feed their creative urges and simultaneously satisfy the desires of their acquisitive audience. Whereas the modernists agitatedly broke artistic conventions, the new generation feverishly rejects the typical mass-market toy models that they grew up with, but injects new concepts, materials, and most importantly, new mass-production techniques, into this otherwise venerable practice.

These new toy designers are filling a vacuum among sophisticated toy freaks who are not interested in mundane, licensed comic and film character action figurines (even the eccentric ones designed as movie tie-ins by the likes of filmmaker Tim Burton), and are appealing to the aesthetic needs of people like me who never bought action figures, but enjoy the design and tactility of these enticingly odd products. Although the main difference between the new art toys and old licensed versions (i.e., Power Rangers, Transformers, G.I. Joe) is their psychotic, post-Pokémon look, they nonetheless have similar marketing goals: Both are produced to be sold in quantity and both are intended to attract followings. Marketing aside, however, these new art toys have something else going for them: attitude. The new plastic, plush, and vinyl toys are more like iconic statuary. They are not actually meant to be played with, but rather displayed (and kept in their smartly designed packages). Making a physical object is the key. What’s more, many exude a fetishistic quality, akin to the American Southwest native Hopi Kachina dolls, which have indirectly influenced many of the new toy makers.

So how have artist toys evolved from the one-offs of the modernists to the multiple characters of the postmodernists? How do they keep from falling into the traps of mainstream toy land? And why is there a common aesthetic that pervades the field and is imbued in even the most outré of these toys?

In the following interviews with the new Geppettos (including two pioneers from the early “new” toy movement, the founder of one of the leading toy emporiums, and three contemporary toymakers), we are given insight into their creative strategies.

David Kirk is the creator of the successful children’s book series Miss Spider’s Tea Party. In the late-1980s he sold his handmade wooden toys out of a storefront in New York’s East Village.

In the ′80s, you made and sold exquisite wooden toys: faces as banks with mouths that opened up to accept the money, and stacking toys, including a skeleton made of rings. How do you feel about the new toy makers’ vinyl and plastic work?

The little plastic figures seem a slightly different area from what I used to do. For one thing, they appear to be part of a movement. There are lots of folks doing similar little beasties made just for today’s collector. It’s a little bit like those gilt-edged plates with pictures of dead movie stars that grandma hangs next to the cupboard with her best china, only this stuff is for guys in their teens and twenties.

They are a little too grotesque to sit next to the china. How do you feel about the art brut or grotesque aesthetic?

I did my share of deliberately ugly toys, but I usually like to concentrate more on what I think is beautiful or just fun. The current grotesque stuff is probably beautiful and fun for the artists who make it and for the collectors who buy it, so I’m all for it.

Your toys were so exquisitely crafted. Do think your stuff is passé?

For one thing, wouldn’t that sort of toy-making have to have been big at some point in order for it to become passé? Maybe I don’t get out enough, but I’ve never seen anybody at any point making toys with a combination of art and mechanics similar to my method. I don’t think I was part of a time, or even ahead of my time. I was just a fluke with an odd skill set.

Why did you start making toys?

Because of my love of the toy robots I have collected since I was two. They broke a lot, and I had to take them apart to repair them, so I got to understand all sorts of simple mechanical systems. In high school, when I got seriously interested in art, I was fascinated by creepy things, like pain, squalor and death, as well as beautiful things like flowers and pretty girls. I got to be good at painting all those subjects, so when I made my toys, it was natural for me to make both cute animals and ugly monsters, both sexy dancing girls and spooky waltzing skeletons.

Who did you design toys for?

They weren’t designed for adults or kids—they were designed for me.

Byron Glaser, with Sandra Higashi, invented Zolo (the postmodern Mr. Potato Head) and the first of the new wave of artist/designer toys.

What inspired you and Sandra Higashi to create Zolo?

We were working on the interior graphics for the FAO Schwarz flagship store on Fifth Avenue in New York City. [We] started to look at the toys that were being offered, and we both thought that there were some really big holes in the market.

Did you love toys as a child?

They have always played a part in our lives. Sandra was very good to her toys and still has some of them. I was much harder on mine.

How did Zolo reflect this passion?

With Zolo, we wanted to make a toy that inspired creativity and engaged whoever was playing with it. We wanted a toy that we would like to have. That was an element that was often missing for us in a lot of the toys that we were seeing around us. We wanted it to be loads of fun but to also inspire a message: that all kinds of shapes, colors, and patterns can work together and that the results can be extraordinary. At first, Zolo was only hand-carved out of wood. We thought as we were creating it that it also should reflect nature, which we are both in awe of. But it was not indestructible, as are so many toys today, so it was another good lesson f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Preface

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Afterword

- Web Directory

- Index

- Books