- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

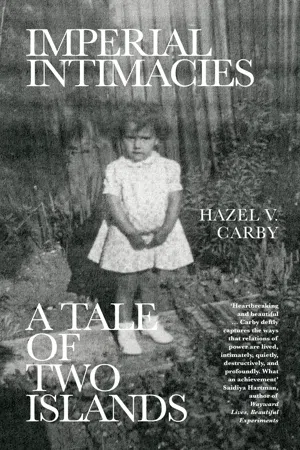

'Where are you from?' was the question hounding Hazel Carby as a girl in post-World War II London. One of the so-called brown babies of the Windrush generation, born to a Jamaican father and Welsh mother, Carby's place in her home, her neighbourhood, and her country of birth was always in doubt.

Emerging from this setting, Carby untangles the threads connecting members of her family to each other in a web woven by the British Empire across the Atlantic. We meet Carby's working-class grandmother Beatrice, a seamstress challenged by poverty and disease. In England, she was thrilled by the cosmopolitan fantasies of empire, by cities built with slave-trade profits, and by street peddlers selling fashionable Jamaican delicacies. In Jamaica, we follow the lives of both the 'white Carbys' and the 'black Carbys', as Mary Ivey, a free woman of colour, whose children are fathered by Lilly Carby, a British soldier who arrived in Jamaica in 1789 to be absorbed into the plantation aristocracy. And we discover the hidden stories of Bridget and Nancy, two women owned by Lilly who survived the Middle Passage from Africa to the Caribbean.

Moving between the Jamaican plantations, the hills of Devon, the port cities of Bristol, Cardiff, and Kingston, and the working-class estates of South London, Carby's family story is at once an intimate personal history and a sweeping summation of the violent entanglement of two islands. In charting British empire's interweaving of capital and bodies, public language and private feeling, Carby will find herself reckoning with what she can tell, what she can remember, and what she can bear to know.

Emerging from this setting, Carby untangles the threads connecting members of her family to each other in a web woven by the British Empire across the Atlantic. We meet Carby's working-class grandmother Beatrice, a seamstress challenged by poverty and disease. In England, she was thrilled by the cosmopolitan fantasies of empire, by cities built with slave-trade profits, and by street peddlers selling fashionable Jamaican delicacies. In Jamaica, we follow the lives of both the 'white Carbys' and the 'black Carbys', as Mary Ivey, a free woman of colour, whose children are fathered by Lilly Carby, a British soldier who arrived in Jamaica in 1789 to be absorbed into the plantation aristocracy. And we discover the hidden stories of Bridget and Nancy, two women owned by Lilly who survived the Middle Passage from Africa to the Caribbean.

Moving between the Jamaican plantations, the hills of Devon, the port cities of Bristol, Cardiff, and Kingston, and the working-class estates of South London, Carby's family story is at once an intimate personal history and a sweeping summation of the violent entanglement of two islands. In charting British empire's interweaving of capital and bodies, public language and private feeling, Carby will find herself reckoning with what she can tell, what she can remember, and what she can bear to know.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imperial Intimacies by Hazel V. Carby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One:

Inventories

The starting point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory. Such an inventory must therefore be made at the outset.

Antonio Gramsci

Where Are You From?

During the first bitterly cold month of 1948 in Britain, a girl was born. Attending primary school at the tail-end of the postwar baby boom, she was one of forty-eight children in her classroom. By the time she was old enough to be aware of her surroundings she lived in Mitcham, then in the county of Surrey, a large part of which lay in the metropolitan green belt. Surrey was famous for the beauty of its North Downs, had more woods than any other county in the UK, and was home to the wealthiest population in Britain. The girl’s mother, Iris, loved having an address in a ‘posh’ county, as if the mere reputation of Surrey could burnish their lives. Iris’s ambition was to move south, deeper into Surrey, to achieve middle-class status and the security it promised, but she never did rub shoulders with the residents of the stockbroker belt. Mitcham was a part of Surrey in name only and her neighbourhood was the last gasp of the working-class estates of South London, the boundary before gracious living began. It was ugly and soulless and, as with similar South London estates, a nursery for white supremacist hatred. In 1965, Mitcham was finally cast out of Surrey and incorporated into the London Borough of Merton. With the change of address Iris’s hopes of class mobility were dashed.

As an adult I can compile an inventory of the history and design of this environment, but to the girl it was as if an incomprehensible higher power had delivered hunks of concrete and steel complete, unexpected and unwelcome. She knew the buildings that materialized around her didn’t grow, that they weren’t organic like trees or animals, but she did not know that the residential suburb in which she lived was the product of a human vision, that it had been planned and developed by people in offices. The four major arteries of the neighbourhood of Pollards Hill radiated outwards from a concrete roundabout, with grass and a signpost in the middle. The girl would throw open her bedroom window. Elbows on the window sill, chin resting on hands, she leant into the long twilight of summer evenings, face lit by the moon as she looked out across a grid of carefully tended squares of grass and narrow beds of flowers partitioned by rows of wooden fences which culminated in a shed or garage. Through a gap between the corner of the Baptist Church and the end of a row of brick terraced houses she could glimpse the roundabout and listen to combustion engines lower in tone as a car, lorry, or motorbike slowed and entered the circle, then rise sharply and suddenly in pitch as the vehicle sped away. Sights, sounds and smells of the night were exalting. Breathing the night deep into lungs it was possible to believe that the roundabout was organic, pliable, a living creature with tentacles drawing vehicles in toward its heart. Abruptly changing its mind, the creature loosened its grip and flung them out screaming into the distance.

At night people were tucked away indoors and the landscape became soft-edged, filled with the shadowy shapes and noises of nonhuman residents: the low guttural warnings of felines stalking each other; squeaks and snuffles from rootling hedgehogs; an ‘urgent sweaty-smokey reek’ and a rustling of undergrowth announcing the presence of a red fox. The girl longed to bring the magic and promise of the outside indoors. One evening she crawled under the shrubbery, trapped a hedgehog in a shoe box, smuggled it into her room and into bed to keep as a friend.

This girl was a wanderer. Her parents worked long hours and the neighbour Iris paid to take care of her children was inattentive. The girl would check to see if her younger brother was contentedly playing with his toys before she crept through the neighbour’s kitchen, scampered down the back-garden path, lifted the latch on the tall wooden gate, closed it behind her and ran.

Once outside she could explore at will; inside the walls of her house she was a girl who was cowed, a shrunken being who worked to render herself invisible. The streets were important avenues of escape, but if the sights, sounds and smells of the night were magical, what the daylight revealed was crass and mundane. She explored streets between rows of modest twostory terraced houses. She scurried across the field of ‘prefabs’ – two-bedroom, prefabricated aluminium, asbestos-clad bungalows resting on slabs of concrete, hastily erected as a solution to the postwar housing crisis. It was dangerous to linger there because the inhabitants registered their disapproval of brown children by throwing stones. The prefabs were meant to be temporary structures but remained for twenty years. As the girl stood staring at the huge estate of six-story maisonettes, she was disoriented by its scale and uniformity. She despaired when the council built a high-density ‘low-rise’ estate of three-story houses and flats because it blocked her route to the hill she loved to climb and roll down.

She traversed an area which stretched from the hill, rising directly behind the roundabout, and fanning out southwest until reaching more than 400 acres of ancient common land. The girl avoided the main roads in favour of walking or biking the network of streets which connected them. She was nearly always headed to the common, where she could breathe and roam, or sit under trees and dream, or dig into the silt of ponds just to see what lived or was buried there. Having crossed the length of the common the girl arrived at the town centre, in which stood the library; the common and the library saved her, but it was many years before she would learn how to draw a map of what she could not see.

The apple trees she climbed, the fragrant wild marjoram and sweet woodruff she brushed past in exploring her favourite places, the open green space of the common and the hill – these were traces of the farms, fields and woodland that for the most part had been paved over. Lying, dreaming, in the long grass of the hill, listening intently to crickets, and creating chains of buttercups, the girl could not imagine the remains of the Celtic fort that lay beneath the soil. In the flora of the landscape there was still evidence of the eighteenth-century physic gardeners who had cultivated 250 acres of lavender, wormwood, chamomile, aniseed, rhubarb, liquorice, peppermint and other medicinal plants.

When her brother was old enough the girl took him to play in the park at the end of Sherwood Park Avenue, site of the vanished Sherwood Farm which had been demolished to build homes for heroes from the First World War. An act of bureaucratic wizardry had replaced local history with national mythology in the district; overlaid onto bricks and mortar was a thin veneer of enchantment evoking the ancient woodlands and footpaths of legend. Three centuries after the actual Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire had been enclosed, its commons turned into private estates, and its various communities dispossessed and dispersed, someone in Mitcham Town Hall had decided that war heroes deserved to walk down roads named after the outlaw Robin Hood and his companions.

Once upon a time, after the war to end all wars, a town planner, sitting at a desk in the council offices, pored over the designs for the future Pollards Hill, racking their brains for names that would enable the residents to erase the horrors of war with fantasies of a medieval world of courtliness while waiting for the bus to take them to work. Robin Hood had already been used twice, once for a Close and again for a Lane. The map was also filling up with references to Abbots, Manors and the Greenwood. Scanning the drawings, the planner came across a small unnamed cul-de-sac protruding from the side of Holly Way. Perhaps this wizard of street names was musing about medieval architecture, or perhaps they consulted one of their architectural colleagues; either way, the shape of the cul-de-sac reminded someone of an oriel, a medieval bay window designed to bring sunlight and fresh air into the interior of a building. A projection into light, an outlook, a turn away from the darkness of war and brutality, a name selected in a moment of hope before another war loomed on the horizon. Oriel was the name given to the Close where the girl would eventually live, a name bequeathed when there were still open green vistas. By the time her family moved in the view was grim: housing estates and prefabs spread to the horizon. But for this girl the world of Robin Hood was living all around her, and, for a while, that was sufficient.

She was content to explore, until she encountered people in shops, the library, the park, at school, or those who quite rightly chased her from their apple trees – people who wanted to know where she was from. The question may appear innocuous, but she came to dread it. Her parents had taught her to hold her head erect, to look directly, without guile, at adults who addressed her, to smile with her eyes not just her teeth, to speak clearly, to be conspicuously open, transparent and honest. Her dad told her that if she did not follow this advice she would be regarded as ‘shifty’, duplicitous and unworthy of attention. The girl absorbed every word because she was eager to be considered a ‘good’ girl, polite and deferential. Not until she was a teenager did she realize that her father had been coaching her on the art of being a ‘good’ black girl, acceptable to white people.

The girl was surprised and disconcerted by the increasingly insistent demands to respond to what she came to think of as The Question! Her father had not prepared her for such intense cross-examination. At first she was confused about what was being asked of her, because she lived in the same neighbourhood as her interrogators. The girl took pride in her navigational skills, which she honed by following the pathways of the medieval land of Robin Hood, her favourite illustrated story book. She could provide anyone who asked with directions to her house via Abbots, Sherwood and Greenwood Roads, but that was not what people wanted from her.

The challenge was to find a satisfactory response to The Question!, for the girl was deceived by the apparent simplicity of the answer. If a child at school wanted to know where she was from she would, as a gesture of friendship, embellish the bare bones of street names with tantalizing scraps of tales from the adventures of Robin Hood, Maid Marian and Friar Tuck: outlaws who robbed from the rich to give to the poor. When it became clear that The Question! demanded a more detailed response than simply giving her current address, the girl offered the name of the village in Devon – Folly Gate – where she was born, and stories of Exmoor extracted from the novel Lorna Doone. This information only confirmed the fears and anxiety that prompted The Question! in the first place. The fact that she was born in England rendered her paradoxical. Adults and children alike considered the possibility of her Englishness derisory and dismissed her accounts as deliberately perverse and misleading. Classmates reproduced, verbatim, the words of their parents: ‘Anyone can see that she is the wrong colour to be from around here, no matter what she says!’ The girl was declared a fool and a liar. Her suggestion that she was native, that she belonged, was an audacious claim in postwar Britain.

There is, it seems to me, an overwhelming tendency to abstract questions of race from what one might call their internal social and political basis and contexts in British society – that is to say, to deal with ‘race’ as if it has nothing intrinsically to do with the present ‘condition of England’. It’s viewed rather as an ‘external’ problem, which has been foisted to some extent on English society from the outside: it’s been visited on us, as it were, from the skies. To hear problems of race discussed in England today, you would sometimes believe that relations between British people and the peoples of the Caribbean or the Indian sub-continent began with the wave of black immigrants in the late forties and fifties …

[Neither right nor left] can nowadays bring themselves to refer to Britain’s imperial and colonial past, even as a contributory factor to the present situation. The slate has been wiped clean.’

Stuart Hall

As I wrote this girl into being I saw that her dread of The Question! haunts the woman the girl became. The Question! is still posed whenever I am regarded as being out of place, seen as an enigma, an incongruity, or a curiosity. The girl was confronted by a bewildering array of contesting national and racialized definitions of self and subject. She was being asked to provide a reason for her being which she did not have. It was sobering to realize that ‘where’ and ‘from’ did not reference geography but the fiction of race in British national heritage. The girl was cautious as she sought to find her way through this cultural maze, but eventually, when all the answers she could invent were rejected, she reluctantly acknowledged that she was being rebuffed for what she was. When she was dismissed, disregarded and disparaged, when she was treated as less than the human she knew herself to be, her chin sunk into her chest, she mumbled and looked sideways out of the corner of her eyes. She became the uncooperative black girl her father did not wish her to be.

Her classmates grew bored with her petulant refusal to reveal a difference their pinches and punches tried to expose. The girl’s body reddened and bruised under fingers poking and squeezing as if unravelling a dense series of knots; knuckles vented their frustration on her brown skin. I can still see this girl refusing to let anyone see her cry. All tears were suppressed until, back at her desk, she concealed her face with a book and let them trickle in silence down her cheeks. In this way books became her refuge.

Far more fearsome than leaving classmates dissatisfied was irritating a teacher, or any curious adult, who asked The Question! They interpreted her silence and shrugs as deliberate perversity, an outright refusal to cooperate. This girl discovered that the adoption of a posture of timidity with a hint of speech impairment was likely to end the interrogation. Answers were mumbled incoherently, with eyes lowered to feet neatly encased in white cotton socks and brown leather Clarks T-bar sandals. Honesty was best avoided in these circumstances: muttering about being born in England condemned her to utter disapproval and the exasperated demand, ‘but where did you come from before that?’ Some adults were convinced she was not telling the truth. Others believed her, an outcome which was far, far worse because then she was accused of being a monstrosity, a ‘half-caste’: the issue of a black father and a white mother. Facts failed her so she turned to fiction.

In this unstable landscape Robin Hood’s adventures were too earth-bound. When the girl was too young to imagine, let alone assert, that she was not accountable to anyone, she invented alternative figures of authority to whom she would account for herself. She concocted a place on earth with the help of DC Comics, where she had found a short story about a scientist in a laboratory examining drops of water through his microscope. In one drop he discovered a universe and, by gradually increasing the magnification, located the Milky Way and eventually planet Earth. The girl’s fantasy involved travelling from another, kinder, galaxy to South London in order to observe the human species in its natural habitat. The mode of travel by which she was transported constantly changed in her head. The girl saw herself as a scientist who, at an unspecified time and place in the future, would be called upon to report the observations recorded in her journals. The plot was short on detail – she had no idea on whose behalf she watched, listened and wrote – but the girl knew that she must not share the nature of her mission with anyone in her family or at school. Standing on her bed leaning out of her window she wondered if the creature inhabiting the roundabout was also an alien, the tall signpost at its centre a transmitter for communication with the mothership. But was it a friend or a foe? Could it read her mind? The girl grew adept living in anticipation of The Question!, which crouched in the shadows waiting to challenge her right to belong. If only those around her knew what she really was!

Resurrecting the world of this girl is risky for my sense of self, a self which has been carefully assembled out of a refusal to acknowledge or remember. I do not wish to provide justifications for my present or past self-creations. The demand that the girl account for her racial self was contemptable. She stumbled for many years before she learnt the difficult lesson that she was not accountable to those who questioned her right to belong. The Question! destabilizes my world still because there is no answer that can satisfy racist conjectures about the shades of brown in skin.

As an adult, living in the United States, I find that unexpressed assumptions determine the terms, conditions and boundaries within which any answer provided will be accepted or dismissed. When I wish to be agreeable, I expend effort analysing which conjectures are in play and attempt to provide an answer which will satisfy expectations and avoid a miserable sense of failure. Failure to be satisfyingly read places the questioner in the awkward position of having to repeat The Question!, which is then patiently re-articulated in a louder and more forceful tone of voice, as if I was hard of hearing:

‘Where are you from?’

Meaning, of course, are you black or white?

Like a cat with its paw on the tail of a hapless mouse, I glean pleasure from watching an interrogator flounder. However, I have to exercise caution in my selection of prey: it is unseemly to torment one’s professional colleagues; it is dangerous to play mind games with British immigration personnel, or with police in the UK; it is asking for serious trouble to joke with officials from Homeland Security or cops in the US of A.

As a result of this lifetime of negotiation, observation and reporting, I am armed with a series of suitable explanations for my various selves. I have fictional and factual justifications for the when, where and why of their being, and carry a potted history for all occasions – such as when a distinguished black professor asked me, ‘How did a nice white girl like you come to study African American literature?’ As a woman, a writer and an academic I am assumed to be out of place: too black to be British, too white, or too West Indian, to be a professor of African American Studies. The Question!, of course, is the wrong question. If I am asked to identify the origin of the selves I have become, without hesitation I describe the various libraries in which the girl I no longer recognize, the girl I have long sin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Part One: Inventories

- Part Two: Calculations

- Part Three: Dead Reckoning

- Part Four: Accounting

- Part Five: Legacies

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration Credits

- Notes

- Index