![]()

Chapter One

The Celestial Motions

The Motion of the Stars

This chapter doubly challenges the imagination. First, it draws on the geometrical or spatial imagination needed to conceive of the motions of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. Second, this chapter, nearly all of which could have been written by an ancient Greek astronomer, invokes the historical imagination by presenting these motions in the way that the Greeks envisioned them, that is, from a geocentric (earth-centered) perspective, which is, of course, how we see them. This approach will not only assist in understanding some of the ancient astronomies, but also facilitate a comprehension of these motions as conceptualized from the modern heliocentric (sun-centered) point of view.

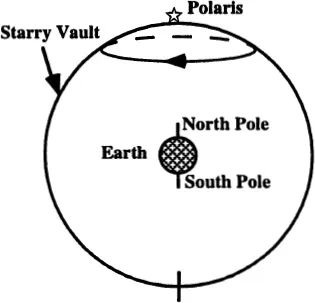

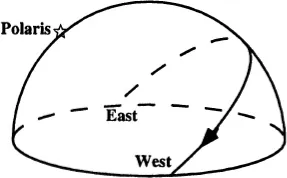

Persons watching the stars over a number of nights see that nearly all of them appear to move in a counterclockwise direction along circles varying in size. The sole stationary stars are Polaris and the southern polar stars. The motions of the stars are identical to what they would be if they were all located on a huge sphere, the starry vault, rotating once approximately every twenty-four hours, and having as its center the earth, which is assumed to be motionless. The sense of rotation of the starry vault is such that a star on its right side is moving out of the page. Typically, a given star will appear to rise on the eastern horizon and set on the western horizon.

South Polar Region

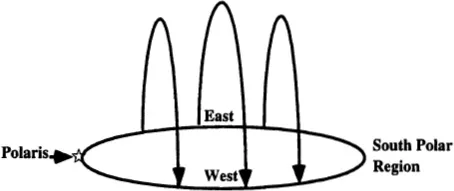

How do persons living on the earth’s equator see the stars move? Polaris and the southern polar stars appear fixed in position. The remaining stars rise perpendicularly to the eastern horizon and set perpendicularly to the western horizon. These motions are represented in the accompanying diagram in which the ellipse represents the horizon plane.

Horizon Plane at Equator

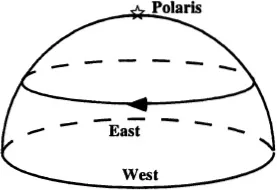

At the north pole, Polaris is seen fixed in position at the zenith (the point in the heavens directly above a person’s location). The other stars appear to move in circles parallel to the horizon plane and centered on Polaris.

Horizon Plan at North Pole

Persons living in Chicago or Boston are located at 42° north terrestrial latitude, i.e., 42° up from the equator. As the next diagram indicates, for such persons, Polaris appears fixed in position, whereas the stars near it move in circles that are always visible. Stars farther down the starry vault move in circles that are cut by the horizon plane.

Horizon Plan at 42° North Latitude

Problems

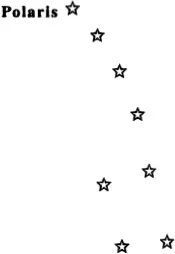

Problem 1: Polaris is the last star in the handle of the little dipper. Draw the motion of the stars in the Little Dipper as seen from 42° north latitude over a period of three hours.

Problem 2: Suppose that there exist only two bodies in the universe: one is identical to the starry vault and the other is a very small spherical planet located at the center of the starry vault. Let us assume that the starry vault rotates once every 24 hours, whereas the planet remains fixed in position, i.e., it neither rotates nor revolves. What motion would an inhabitant of the starry vault, convinced that the starry vault is at rest, attribute to the planet at the center? Represent this by means of a diagram. Are there any conclusive arguments that an inhabitant of the planet could formulate to prove that the starry vault is rotating? Or are there arguments that the inhabitant of the starry vault could use to show that the planet is rotating?

Little Dipper

The Motion of the Sun

First, some definitions:

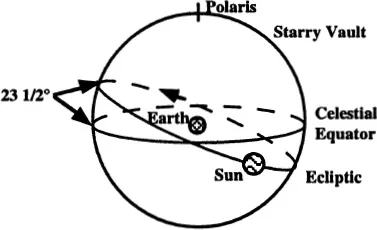

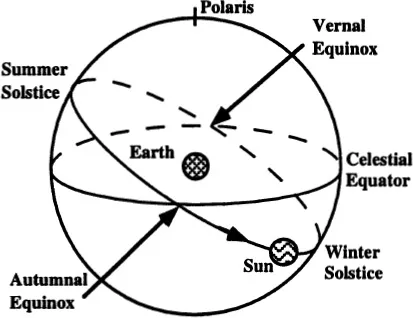

Celestial Equator: The celestial equator is the line on the starry vault that lies directly above the earth’s equator. Some point on the celestial equator is always at the zenith of a person living on the earth’s equator.

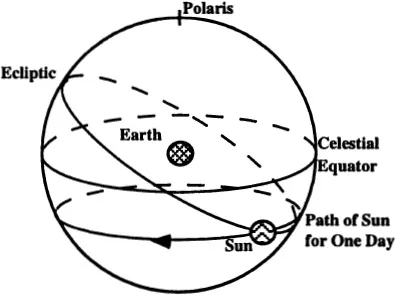

Ecliptic: The ecliptic is a line on the starry vault on which the sun always appears to be located. It is the apparent yearly path of the sun or the projection of the path of the sun on the starry vault during one year. The ecliptic is inclined at 23 1/2 degrees to the celestial equator. The sun completes one circuit of the ecliptic every 365.24220 days. From this it is evident that the sun moves approximately one degree each day on the ecliptic. Note that whereas the stars move from east to west, the motion of the sun on the ecliptic is from west to east. Let us now combine the motion of the starry vault with that of the sun. It is important to remember that the ecliptic is simply a line among the stars; it is like a seam on a basketball. If a basketball is rotated, its seam rotates with it. Correspondingly, the ecliptic rotates with the starry vault. Consequently, each day the sun makes one revolution around the earth along with the starry vault; however, the sun also moves about one degree per day along the ecliptic, moving in the opposite direction. As an aid to visualizing this, imagine an ant walking slowly down the side of a rapidly rotating basketball. The path of the ant from the point of view of the basketball is a straight line, but if seen from a fixed observer at a distance, the ant will appear to be moving along a helix. The next diagram shows the motion of the sun for one day.

Additional definitions are now needed.

Vernal Equinox: The point on the starry vault where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator with the sun moving toward the northern half of the heavens. The sun is at the vernal equinox around March 21. When the sun is at an equinoctial point (vernal or autumnal equinox), people on earth in most cases experience days and nights of equal length.

Summer Solstice: The most northerly point on the ecliptic. The sun is at the summer solstice around June 22.

Autumnal Equinox: The point on the starry vault where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator with the sun moving toward the southerly half of the heavens. The sun is at the autumnal equinox around September 23.

Winter Solstice: The most southerly point on the ecliptic. The sun is at the winter solstice around December 22.

These definitions can be presented diagrammatically.

The discussion of the sun’s motion presented up to this point can be used to explain the seasons. This will also provide practice in applying these ideas. Many inhabitants of the northern hemisphere believe that summer is hot because the sun is closer at that time than in winter. In fact, the sun is farther from the earth in summer than in winter. The chief reason why summer is warm and winter cold...