![]()

1

The Collapse of Organized Labor in the United States

Why should we worry about organizing groups of people who do not appear to want to be organized? I used to worry about … the size of the membership. But quite a few years ago I stopped worrying about it, because to me it doesn’t make any difference.

—Former AFL-CIO president George Meany1

Speaking in 1972, the long-standing leader of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) couldn’t see what was right around the corner for his organization. The “size of the membership” shrank at an accelerating pace throughout the 1970s and 1980s. And what Meany said mattered. Even late into his nearly three-decade reign, a rival labor leader admitted, “Meany is the boss … he has achieved centralization of authority,” a feat previous labor leaders failed to accomplish.2 Meany’s opinion of and attitude toward organizing set the tone for much of the labor movement. This complacency about organizing exemplified the postwar era of “business unionism” in the United States. During this period, many unions grew into enormous bureaucracies, overseeing millions of members, millions of dollars, and large staffs charged with handling workplace matters. The organizing arms of these unions, meanwhile, “tended to enter a state of atrophy,” according to the sociologists Rick Fantasia and Kim Voss.3 At the same time, battles over collective bargaining became routinized and scripted, sapping much of the grassroots militancy that had characterized earlier upsurges in unionization. Instead, members began to view their union as a service provider: In exchange for a fee (or dues), the union delivered certain predictable benefits. Lost in the transformation was the sense of rank-and-file ownership of the union—and with it the capacity for collective mobilization that could reenergize labor’s organizing muscles, or fend off employer onslaughts on existing unions.

In recent years many labor scholars suggested that organized labor’s transformation from a broad-based social movement to a narrow service provider was a primary factor explaining unions’ present malaise.4 This perspective argued that during the decades spent contentedly servicing existing memberships, many unions lost touch with their rank and file, and were caught unawares by brewing economic transformations and growing employer backlash. Much of this work is dedicated to identifying the organizing blueprints that have proven successful in the contemporary antiunion climate—blueprints that had nearly disappeared during the 1970s and 1980s.5 And indeed, those unions that have embraced the repertoire of tactics and strategies encompassing “social movement unionism” have scored some remarkable victories of late, including the widely-heralded “Justice for Janitors” campaign devised by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). From this perspective, then, organized labor’s decline in the United States was due in no small part to organized labor itself.

Two countervailing arguments call this conclusion into question: the relative failure of recent unionization drives to reverse membership declines, and parallel unionization trends in other major industrialized nations. First, even the most innovative and energetic unions in the United States have learned that organizing in the present economic and institutional environment is exceedingly difficult. These unions have learned the lesson through bitter experience. It is not only labor scholars who have argued that unions’ current predicament stems from labor’s own complacency; after all, many labor leaders also rallied around this view. Over the past two decades schisms have roiled the labor movement, including the 1995 leadership transition within the AFL-CIO and the 2005 split between the AFL-CIO and the newly formed Change to Win coalition of unions. Frustration with a lack of organizing played a major role in both developments. During the early 1990s many unions saw the AFL-CIO, then headed by Lane Kirkland, as unresponsive to the urgent needs of the movement and complacent in the face of the economic and political challenges facing American workers. John Sweeney emerged as the consensus candidate of the insurgents and assumed the presidency of the federation in 1995, promising to inject new energy into the movement in part by redoubling organizing efforts. Just ten years later, unions such as SEIU had grown frustrated with Sweeney’s lack of progress and broke off to form the rival Change to Win federation—once again promising to focus heavily on organizing. But neither the leadership transition at the AFL-CIO nor the new competition between Change to Win and the AFL-CIO has stemmed membership losses.

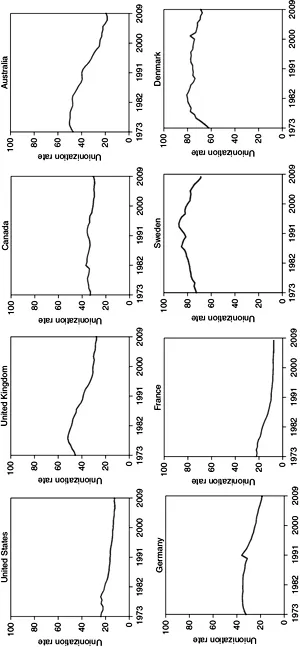

Second, for those who emphasize lethargic (or nonexistent) organizing as the primary cause of labor’s woes in the United States, a complicating factor is the international picture. Falling membership rates are by no means a distinctively American phenomenon. Indeed, in some countries unions underwent steeper declines than in the United States. Figure 1.1 displays unionization trends for eight advanced industrial democracies from 1973 to the present. All these countries—dissimilar in so many other ways—experienced at least some union membership erosion. The exact timing and pattern of the declines differ, with countries like the United States and France experiencing steady, linear losses throughout the years covered, while other countries like Sweden show a more curvilinear pattern, peaking in the middle of the series before declining again during the early years of the twenty-first century. The sizes of the membership losses vary as well. Canada’s unionization rate in 2009 stood 21 percent lower than its peak in the early 1980s, a minor drop-off compared to other nations. Between 1973 and 2009, unionization rates in the United States halved. In Australia, membership peaked in 1976, when unions had successfully organized over half the workforce. By 2009, union rolls had fallen by 60 percent relative to their highest level. In France, they fell by more than two-thirds.6

Now it could be that labor unions in all these countries, to one degree or another, simply lost their organizing initiative over the period covered by the figure. Some variant of “business unionism” may have existed beyond the U.S. border, draining other labor movements’ energy, creativity, and drive to reach out and organize new members. And perhaps unions in those countries that were able to limit losses, like in Canada, remained more attentive to organizing in the postindustrial period. There certainly may be some merit to that argument. But a more comprehensive explanation of union decline likely lies outside of the relative zeal with which contemporary unions are seeking to expand their memberships.

Figure 1.1. Unionization rates by country, 1973–2009. Note: Samples restricted to employed wage and salary earners. Source: Visser 2009.

Public Approval

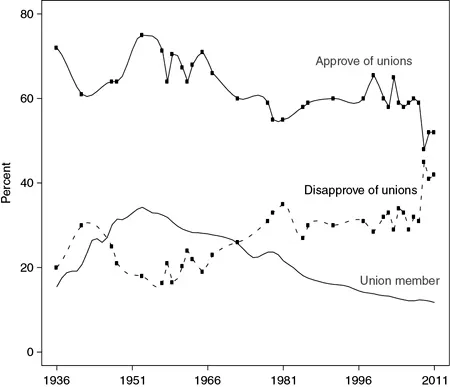

Organizing is impossible if there is no demand for unionization. Declining popularity rates constitute another potential explanation for labor’s collapse. Gallup has surveyed Americans on their opinion of organized labor for seventy-five years. In 2009, for the first time ever, union approval rates fell below 50 percent—although they rebounded slightly in more recent years. Disapproval rates, meanwhile, doubled from their low point in the 1950s. Could it be that “resentment has replaced solidarity,” as the New Yorker’s financial writer James Surowiecki recently asked?7 And could this growing resentment by many Americans help explain labor’s contemporary plight?

In a word, no. Unions in the United States are not now nor have they ever been all that unpopular. Figure 1.2 charts trends in unionization as well as responses to the Gallup poll question asking Americans whether they “approve or disapprove of labor unions.” As shown, union disapproval rates in the United States never reach 50 percent. Approval rates have declined in recent years, and they remain well below their 1953 peak of 75 percent. Yet despite 2009’s dip, today a majority of the American public approves of unions.

It is important to highlight the unionization trend during these years. From the mid-1950s onward, organization rates fell, and with them the fraction of the Gallup samples who were union members. Assuming these samples were roughly representative of the U.S. workforce, the portion of interviewees who belonged to a labor union declined by about two-thirds between 1953 and 2011. We know that union members approve of unions by overwhelming majorities—upward of 90 percent.8 The fact that union approval has not fallen further speaks to unions’ popularity among unorganized Americans. A recent poll of nonmanagerial, nonunion workers found that over half would vote for a union if given the opportunity.9 The fraction of the U.S. workforce that is nonunion and desires union representation is higher in the United States than in peer nations such as Canada, Britain, and Australia.10 If the unionization rate in the United States was simply a function of unfilled demand for unions, then the rate would stand at roughly 50 percent.11

Figure 1.2. Union approval and unionization rates, 1936–2011. Notes: Gallup data are not available for all years. Approval and disapproval trend lines are two-period moving averages. For years with more than one Gallup survey, estimates represent the average rating for the year. Unionization rates for 1948–2011 are for all wage and salary workers; for 1936–1947, unionization rates are for all employed workers. Source: Approval and disapproval ratings are from Gallup. Unionization data for 1973–2011 are from Hirsch and Macpherson’s Unionstats database, based on the CPS-May and CPS-MORG files. See www.unionstats.com. Unionization rates before 1973 are from Mayer (2004) and are based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

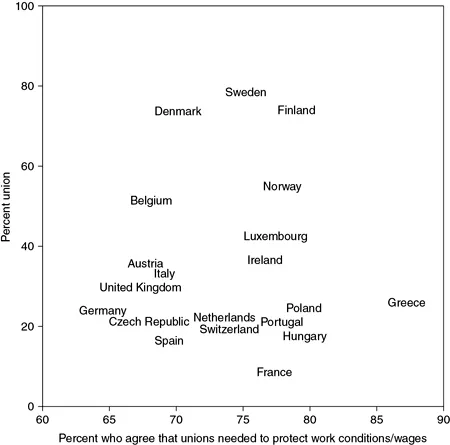

The relationship between approval of unions and the overall unionization rate is weak not just in the United States, it is also weak in Europe. Figure 1.3 plots the fraction of the population that supports unions and the overall unionization rate for twenty European nations in 2002. As shown, there is little correlation between approval and organization rates.

Figure 1.3. Union approval and unionization rates in Europe, 2002. Source: Union opinion data come from the European Social Survey (percent agree or strongly agree). Unionization rates are from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In the recent state skirmishes over collective bargaining rights of public employees, polls consistently found that one group in particular supports greater restrictions on public-sector unions: Republicans.12 Republican—and conservative—disapproval of unions extends beyond the public sector. In recent years, the partisan gap in union approval has exceeded 50 percentage points. In 2011, for example, only a quarter of Republicans expressed support for organized labor, versus nearly 80 percent of Democrats.13 Why do right-wing Americans oppose unions? Similar to many American employers (and there is substantial overlap between the groups), conservatives often believe unions interfere with the workings of the free market, and therefore are bad for the economy. For others, the very notion of a union challenges the values of individualism and self-reliance.

This conservative disapproval of labor unions is not new. The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page has long reflected the perspectives of economic conservatives in the United States. And its decidedly antiunion slant extends back over half a century. Typical editorials include “Stooges Unwanted” (1951), about union influence in politics, “Hoodwinking Consumers” (1974), about the costs of unionization to customers, and “American Federation of Lemmings” (1983), about the AFL-CIO’s policy prescriptions.

Employers’ opposition to organized labor also has a long lineage, although a unified business stance against labor took some time to coalesce. The historian Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, for example, suggests that division within the business community existed during the early decades of the twentieth century, with some employers not adamantly opposed to the nation’s fast-growing labor unions.14 The political scientist Peter Swenson echoes Fones-Wolf’s contention that certain employers did not initially resist labor, even showing that in various sectors “employer organizations welcomed well-organized unions” who helped prevent competitors from undercutting existing businesses.15 However, by the late 1930s, “a partial mobilization” by the business community began to oppose pro-union policies.16 The National Association of Manufacturers, for example, lobbied furiously against the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the 1935 law that enshrined collective bargaining rights in the country. Labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein describes the 1940s and 1950s as decades marked by “corporate inspired ideological warfare” against organized labor.17

In sum, the relationship between public approval and unionization rates is weak in the United States and abroad. If it were not, the nation’s unionization rate would be four times its current size. It is certainly the case that conservative Americans—especially those most concerned with corporate interests—largely oppose unions. This opposition has been with us for some time; according to labor activist Richard Yeselson, “there is no more consistent trope of conservative ideology stretching back over a century than a nearly pathological hatred of unions.”18 What has changed, then? In part, the ability of employers to accomplish their long-standing antiunion agenda. This ability has three core antecedents: one, economic changes; two, the interaction between those economic developments and collective bargaining institutions; and three, political developments, which helped reinforce the employers’ agenda.

Economics

Paramount among the major economic transformations occurring over the past decades was t...