eBook - ePub

My Crazy Century

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access My Crazy Century by Ivan Klíma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

1

My first memory is of something insignificant: One day Mother took me shopping in an area of Prague called Vysočany and asked me to remind her to buy a newspaper for Father. For me, it was such an important responsibility that I still remember it. The name of the newspaper, however, I no longer recall.

My parents rented two rooms and a kitchen in a house that was occupied by, in addition to the owner, a hunting dog with the elegant name of Lord. Birds, mainly blackbirds and thrushes, nested in the garden. When you are four or five, time seems endless, and I spent hours watching a blackbird hopping about the grass until he victoriously pulled a dew worm out of the earth and flew back with it to his nest in the juniper thicket, or observing how snowflakes fell on our neighbor’s woodshed roof, which to me was like a hungry black-headed monster, gobbling up the snowflakes until it was sated and only then allowing the snow to gradually accumulate on the dark surface.

From the window of the room where I slept there was a view into the valley. From time to time, a train would pass, and at the bottom of the vale and on the opposite slopes huge chimneys towered into the sky. They were almost alive and, like the locomotives, they belched forth plumes of dark smoke. All around there were meadows, small woodlots, and thick clumps of shrubbery, and when the trees and bushes were in bloom in the springtime I began to sneeze, my eyes turned red, and I had trouble breathing at night. Mother was alarmed and took my temperature and forced me to swallow pills that were meant to make me perspire. Then she took me to the doctor, who said it was nothing serious, just hay fever, and that it would probably afflict me every spring. In this he was certainly not wrong.

It was in one of those chimneyed factories, called Kolbenka, that my father worked. He was an engineer and a doctor, but not the kind of doctor who cures people, Mother explained: He cured motors and machines and even invented some of them. My father seemed larger than life to me. He was strong, with a magnificent thatch of black hair. Each morning he shaved with a straight razor, which I was not allowed to touch. Before he began lathering his face, he sharpened the razor on a leather belt. Once, to impress upon me how terribly sharp it was, he took a breakfast roll from the table and very gently flicked it with the blade. The top half of the roll toppled onto the floor.

Father had a bad habit that really annoyed Mother: When he walked along the street, he was always spitting into the gutter. Once when he took me for a walk to Vysočany, we crossed the railway tracks on a wooden bridge. A train was approaching, and to amuse me Father attempted to demonstrate that he could spit directly into the locomotive’s smokestack. But a sudden breeze, or perhaps it was a blast of smoke, blew my father’s new hat off and it floated down and landed on an open freight car heaped with coal. It was then I first realized that my father was a man of action: Instead of continuing on our walk, we ran to the station, where Father persuaded the stationmaster to telephone ahead to the next station and ask the staff to watch the coal wagons and, if they found a hat on one of them, to send it back. Several days later Father proudly brought the hat home, but Mother wouldn’t let him wear it because it was covered in coal dust and looked like a filthy old tomcat.

Mother stayed at home with me and managed the household: She cooked, did the shopping, took me on long walks, and read to me at night until I fell asleep. I always put off going to sleep for as long as I could. I was afraid of the state of unconsciousness that came with sleep, afraid above all that I would never wake up. I also worried that the moment I fell asleep my parents would leave and perhaps never come back. Sometimes they would try to slip out before I fell asleep and I would raise a terrible fuss, crying and screaming and clutching Mother’s skirt. I was afraid to hold on to Father; he could yell far more powerfully than I could.

It is not easy to see into the problems, the attitudes, or the feelings of one’s parents; a young person is fully absorbed in himself and in the relationship of his parents to himself, and the fact that there also exists another world of complex relationships that his parents are somehow involved in eludes him until much later.

Both my parents came from poor backgrounds, which certainly influenced their way of thinking. My mother was the second youngest of six children. Grandfather worked as a minor court official (he finished only secondary school); Grandmother owned a small shop that sold women’s accessories. Her business eventually failed—the era of large department stores was just beginning and small shops couldn’t compete.

Grandpa and Grandma were truly poor. The eight-member family lived in a two-room flat on Petrské Square, and one of those rooms was kept free for two subtenants, whose contribution ensured that my grandparents were able to pay the rent. Nevertheless, they made certain their children got an education: One of my aunts became the first Czech woman to get a degree in chemical engineering, and my mother graduated from a business academy.

Two of Mother’s brothers were meant to study law, but they went into politics instead. I hardly knew them and can’t judge whether they joined the Communist Party out of misguided idealism or genuine solidarity with the poor, who at that time still made up a sizable portion of the population. After having immigrated to the Soviet Union, both of them returned to the German-occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on orders from the party. Given their Jewish background, this was a suicidal move and certainly not opportunistic.

My mother was fond of her brothers and respected them, but she did not share their convictions. It bothered her that the Soviet Union meant more to them than our own country and that they held Lenin in higher esteem than they did Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

On the day I turned six, Masaryk died. For my birthday, my mother promised me egg puffs, which were an exceptional treat. To this day I can see her entering the room with a plateful of the pastries and sobbing loudly, the tears running down her beautiful cheeks. I had no idea why; it was my birthday, after all.

Father seldom spoke about his childhood. He seldom spoke to us about much of anything; he would come home from work, eat dinner, sit down at his worktable, and design his motors. I know that he lost his father when he was thirteen. Grandmother was able to get by on her husband’s tiny pension only because her brother-in-law (our only wealthy relative) let them live rent-free in a little house he bought for them just outside Prague. When he was studying at the university, my father supported himself by giving private lessons (as did my mother), but then he got a decent job in Kolbenka and managed to hang on to it even during the Depression. Still, I think the mass unemployment that affected so many workers influenced his thinking for a long time afterward.

I hadn’t yet turned seven when the country mobilized for war. I didn’t understand the circumstances, but I stood with our neighbors at the garden gate and watched as columns of armored cars and tanks rolled by. We waved to them while airplanes from the nearby Kbely airport roared overhead. Mother burst out crying and Father railed against the French and the English. I had no idea what he was talking about.

Soon after, we moved across town to Hanspaulka. Our new apartment seemed enormous; it had three rooms and a balcony and a large stove in the kitchen. When the stove was fired up, hot water flowed into strange-looking metal tubes that Father called radiators, although they bore no resemblance to the radio from which human voices or music could be heard. It was in this new apartment that my brother, Jan, was born. The name Jan is a Czech version of the Russian Ivan, so if we had lived in Russia our names would have been the same.

When Father brought Mother and the newborn home from the maternity hospital, there was a gathering of both our grandmothers, our grandfather, and our aunts, and they showered praises on the infant, who, in my opinion, was exceptionally ugly. I recall one sentence uttered by Grandfather when they gave him the baby to hold: “Well, little Jan,” he said, “you haven’t exactly chosen a very happy time to be born.”

*

Until then I had never heard the word “Jew,” and I had no idea what it meant. It was explained to me as a religion, but I knew nothing about religion: My school report card stated “no religious affiliation.” We had the traditional visitation from Baby Jesus at Christmas, but I had never heard anything about the Jesus of the Gospels. Because I had been given a beautiful retelling of the Iliad and the Odyssey, I knew far more about Greek deities than I did about the God of my ancestors. My family, under the foolish illusion that they would be protecting my brother and me from a lot of harassment, had us christened. Family tradition had it that some of my mother’s distant forebears had been Protestants, and so my brother and I were christened by a Moravian church pastor from Žižkov. I was given a baptismal certificate, which I have to this day, but I still knew nothing of God or Jesus, whom I was meant to believe was God’s son and who, through his death on the cross, had liberated everyone—even me—from sin and death.

Father may have been upset with the English, but one day my parents informed me that we were going to move to England. I was given a very charming illustrated textbook of English called Laugh and Learn, and Mother started learning English with me.

I asked my parents why we had to move out of our new apartment that all of us were fond of. Father said I was too young to understand, but he’d been offered a good job in England, and if we stayed here, everything would be uncertain, particularly if we were occupied by the Germans, who were ruled by, he said, an upholsterer, a good-for-nothing rascal by the name of Hitler.

One snowy day the Germans really did invade the country.

The very next morning complete strangers showed up at our apartment speaking German—or, more precisely, shouting in German. They walked through our beautiful home, searched the cupboards, looked under the beds and out on the balcony, and peered into the cot where my little brother began crying. Then they shouted something else and left. I wanted to know who these people were and how they could get away with storming through our apartment as though they owned it. Mother, her face pale, uttered another word I was hearing for the first time: gestapo. She explained that the men were looking for Uncle Ota and Uncle Viktor. She lifted my brother from his cot and tried to console him, but as she was so upset, her efforts only made Jan cry harder.

At dinner, Father told Mother it was time to get out. But in the end, we didn’t move to England because, although we already had visas, Grandmother’s had yet to arrive. To make matters worse, our landlord, Mr. Kovář, served us with an eviction notice. He didn’t want Jews in his building anymore. Naturally no one told me anything, and I still had no idea that I was so different from other people it might give them a pretext to kill me.

We moved into a newly completed building in Vršovice, where again we had only two rooms. Immediately after that, the war began.

I can no longer recall exactly how that apartment was furnished. I vaguely recollect a green ottoman, a bookcase on which an azure blue bowl stood, and, hanging on the living room wall, a large map of Europe and northern Africa where Father followed the progress of the war. Apparently it was not going well. The German army swiftly occupied all those colored patches on the map representing the countries I had learned unerringly to recognize: the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Norway, Yugoslavia. To top it all off, the good-for-nothing rascal Hitler had made an agreement with someone called Stalin, who ruled over the Soviet Union, decreeing that their respective empires would now be friends. This news took Father by surprise. I also understood that it was a bad sign, since the area on the map marked Soviet Union was so enormous that if the map was folded over, the Soviet Union could completely cover the rest of Europe.

When we first moved into our new home, there were lots of boys and girls to play with. Our favorite game was soccer, which I played relatively well, followed by hide-and-seek because there were many good hiding places in the neighborhood.

Then the protectorate issued decrees that banned me from going to school, or to the movies, or into the park, and shortly thereafter I was ordered to wear a star that made me feel ashamed because I knew that it set me apart from the others. By this time, however, Germany had attacked the Soviet Union. At first Father was delighted. He said that it would be the end of Hitler because everyone who had ever invaded Russia, even the great Napoleon himself, had failed, and that had been long before the Russians had created a highly progressive system of government.

Of course it all went quite differently, and on the large map, the vast Soviet Union got smaller each day as the Germans advanced. Father said it couldn’t possibly be true. The Germans must be lying; they lied about almost everything. But it turned out that the news from Hitler’s main headquarters was mostly true. Whenever they advanced, they posted large V’s everywhere, which stood for “victory,” while at the same time they issued more and more bans that eventually made our lives unbearable. I was no longer allowed out on the street at night; I couldn’t travel anywhere by train; Mother could shop only at designated hours. We were living in complete isolation.

Father’s beautiful sister, Ilonka, managed to immigrate to Canada at the last minute. We were not permitted to visit Mother’s eldest sister, Eliška, or even mention her name, since she had decided to conceal her origins and try to survive the war as an Aryan. Father thought she would have a hard time succeeding, but in this, once again, he was wrong. Mother’s youngest sister fled to the Soviet Union, and her Communist brothers went into hiding for a while before they too fled. When the party recalled them to work in the underground here, the Germans quickly tracked them down, arrested them, and shortly thereafter put them to death. Mother’s other sister, Irena, moved in with us. She was divorced, but it was only for show, since her husband, who was not Jewish, owned a shop and a small cosmetics factory that, had they not divorced, the Germans would have confiscated. The family had no idea, since very few people had any such ideas then, that they had offered my aunt’s life for a cosmetics business.

In our apartment building there were two other families wearing the stars—one on the ground floor and the second on the top floor. In September 1941, the family living on the ground floor, the Hermanns, were ordered to leave for Poland, apparently for Łódź, in what was called a transport.

I remember their departure. They had two daughters slightly older than I was, and both girls were dragging enormous suitcases on which they had to write their names and the number of their transport. As the Hermanns left, people in our building peered out from behind their doors, and the more courageous of them said goodbye and reassured them that the war would soon be over and they’d be able to return. But in this, everyone was wrong.

My parents rushed about trying to find suitcases and mess tins, and they bought medicines and fructose in a recently opened phar...

Table of contents

- Cover

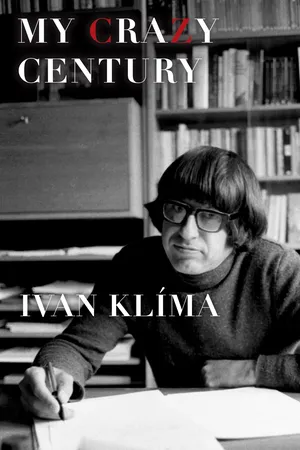

- MY CRAZY CENTURY

- Also by the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Note from the Publisher

- Contents

- MY CRAZY CENTURY

- Prologue

- PART I

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- PART II

- Chapter 14

- Photo Insert

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Epilogue

- Essays

- Ideological Murderers

- Utopias

- The Victors and the Defeated

- The Party

- Revolution Terror and Fear

- Abused Youth

- The Necessity of Faith

- Dictators and Dictatorship

- The Betrayal of the Intellectuals

- On Propaganda

- Dogmatists and Fanatics

- Weary Dictators and Rebels

- Dreams and Reality

- Life in Subjugation

- Occupation, Collaboration, and Intellectual Riffraff

- Self-Criticism

- (Secret Police)

- The Elite

- Back Cover