![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Contradictions

In April 2013 I was fortunate to meet an inspiring group of soldiers from the Irish army in County Cork (Figure 1.1). They were part of the Cork Western Front Association and all had relatives who had served in Irish regiments of the British army during the Great War. Today, Cork is known for the stand it took against the British during the Anglo-Irish War of 1919–21, as well as its ardent republicanism during the civil war of 1922–1923. In the period 1917–23, 747 people were killed for political reasons in Cork city and county in the struggle over self-government.1

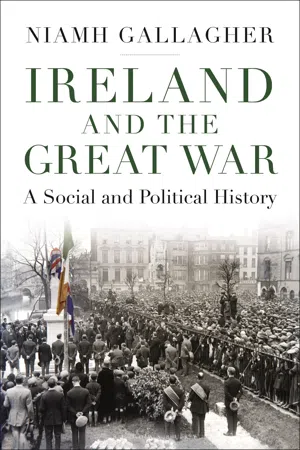

Figure 1.1 Unveiling the Great War memorial in Cork, 1925. Courtesy of Adrian Foley.

Yet one of my guides, Adrian Foley, showed me the above photograph which encapsulates a forgotten dimension of the history of a notorious Irish county. The picture is from a cracked glass plate which Adrian found hidden in one of the local museums. It shows the turnout of people at the unveiling of the Cork Great War memorial in March 1925. This was only four years after parts of the city had been burnt to the ground by the British Crown forces in one of the most infamous reprisals to have happened during the Anglo-Irish War2 ; at least four years after the county had earned the nickname of ‘rebel Cork’ as a tribute to its resistance to British authority during that conflict; and, according to the orthodox histories, long after Irish Catholics had turned their backs on the British war effort and those who had fought for the Allied cause to pursue Irish independence instead.

This image shows ex-soldiers, many of whom had been in the local British infantry regiment, the Royal Munster Fusiliers (RMF), surrounding the war memorial holding their hats in their hands as a mark of respect to comrades who had fallen in action; women and children standing behind them in memory of lost family members; local dignitaries with sashes and wreaths seemingly united in the object of the day; and of course the crowd, packed from one end of the street to the other in a widespread demonstration of mourning and remembrance. More striking perhaps are the flags: the republican tricolour in the foreground symbolizing Ireland’s independence from Britain, which republicans and the constitutional nationalists before them fought hard to achieve. Yet behind it lies the Union Flag draped over the war memorial, demonstrating that the flag which many Irish people had recently fought against to gain independence still held some meaning, even if it was not a political attachment, when they remembered Cork’s involvement in the Great War.

All classes and creeds turned out in Cork for the unveiling of the memorial.3 It was an event that would have touched a wide cross-section of people because by the end of 1917, 10,106 men had served in the war from Cork city and county: 5.17 per cent of the total male population.4 By 1924 the British Legion Society of Ireland estimated that ex-servicemen comprised almost 21 per cent of Cork city’s population (i.e. 16,000 men out of a population of 76,673).5 A total of 3,774 men were killed, including those who had tangible connections to the city and county: more than five times as many as Cork people killed in the struggle for independence.6 This large figure does not diminish the significance of the lives lost in the political struggles from 1917 to 1923, and it is possible that those who turned out on this day in Cork were also mourning for the Irish who fell in these wars as well given the complications that arose over commemorating the civil war in Ireland, as Anne Dolan has brought to light.7 However, it puts the losses of the Great War into perspective, as Cork was a largely Catholic county (356,269 Catholics: 35,756 Protestants) and is more remembered in twentieth-century Irish history for its revolutionary past than for its involvement in the Great War.8

Figure 1.2 Mourners surround cross dedicated to the 16th (Irish) Division, College Green, Dublin, Armistice Day, 1924. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

I became even more intrigued by the photograph when I discovered that such gatherings of ex-servicemen were not unique to Cork but were common across interwar urban Ireland at a time when the new Irish state was attempting to diminish the legacy of British administration. In Louth, at least 2,475 men fought in the war, 816 of whom were killed or died of wounds up to 1925.9 Of these men 2,173 came from Dundalk and Drogheda – towns whose male populations in 1911 were 6,773 and 6,055 respectively. Some servicemen only had affiliations to Louth and the recruitment figures also included some women, but most of the fallen came from these towns, representing a significant percentage of the population to have taken part in the conflict.10 Armistice Day commemorations actually flourished in Louth during the 1920s and 1930s which, as Donal Hall has argued, ‘is an indication of a society much more at ease with the legacy of World War I than some recent historical studies would have us believe’.11 Similarly in Kilrush, Co. Clare, a seaport town of 3,666 people (3,533 of whom were Catholic), more than 414 men fought in the war; 36 were killed.12 The imprint of the conflict on Kilrush was obvious in later years, as some republicans felt that the town ‘was not a great Sinn Féin town’ and ‘did not fall into line’ with the republican party’s desire to eradicate ‘Britishness’ in the new Irish state because of, in part, its participation in the war. Eamon de Valera, the Sinn Féin leader and long-serving statesman, reputedly claimed that Kilrush was really ‘a little British town’.13

Visual evidence of huge crowds commemorating the war in Dublin from 1923 to 1930, as well as in smaller largely Catholic centres such as Longford and Bray, reveals that Cork was not unique in remembering its contribution to the British war effort during the interwar period (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).14

Figure 1.3 Armistice Day, Market Square, Longford, 1925. Reuters via British Pathé.

These images illuminate the central paradox of the Irish war experience: How could so many people turn out to mourn their war dead in towns and villages across Ireland when Catholics had supposedly turned their backs on the Allied war effort during the conflict itself? And why did Protestants and Catholics often turn out together at remembrance events when the conflict had deepened the domestic political divisions between them?

The answers to these questions lie partly in the years which followed the Great War and historians have offered different explanations for the large turnouts. In Cork, the unveiling of the memorial took place on the feast of St Patrick’s Day, a public celebration, while in Dublin the authorities were keen to make a gesture to ‘Protestant capitalism’ due to that group’s influence on the political and economic life of the city.15 But these explanations do not sufficiently explain why so many Irish people of both creeds turned out together to commemorate a conflict that the majority of people – the Catholic-nationalist population – allegedly did not support. The large turnouts can only be explained by looking at the war years themselves – the years to which this book is dedicated – to understand what exactly happened in wartime Ireland to have encouraged these demonstrations of inter-communal remembrance. The ‘long shadow’ of the conflict is still evident today, embodied within organizations such as the Cork Western Front Association.16 Adrian Foley is one of many members who went to great lengths to trace the war records of relatives that served in the war. He discovered that his great-grandfather, William Foley, a soldier of the RMF and a Catholic who survived the conflict, participated in ex-servicemen’s associations until his death in 1960. The organization’s determination to reclaim the memory of these British ex-servicemen is a local manifestation of a wider process of reclaiming the memory of the 1914–18 war in Ireland, one which was especially evident in the recent centenary, at which the conflict was put at the centre of Irish political life in both the North and the South.

The subject of this book is thus the war years themselves, 1914 to 1918, and Irish responses to the Great War on the home front in Ireland and other Irish diasporic communities. Undoubtedly the years 1914 to 1918 have been the subject of much research due to the domestic political developments from 1912 to 1923 that set Ireland on a path towards independence, partition and civil war. In the historiography of the war years, many aspects of Irish men’s performance at the front and of the revolutionary crisis at home have been examined in great detail by historians, but astonishingly we still lack a systematic analysis of the home front in Ireland and other Irish home fronts in each and every year of the war. How did people feel about and behave towards the conflict? In what ways did they engage with the war effort? Did they support its objectives and why? How did their attitudes and behaviour change over time? How did engagement differ between urban and rural areas? And why have historians – and for a long time, much of the public – believed that Irish Catholics were broadly against the war effort? This book attempts to provide some answers to these questions. It aims to shift the emphasis of Irish involvement away from enlistment and the respective desires of unionism and nationalism onto the war effort itself. Its foremost concern is the Catholic Irish (though Protestants also appear in this study), as it is the commitment to the Allied war effort of this large and diverse group that is most in question, especially from 1916 to 1918 when the character of Irish nationalism changed.

However, let me be clear about some matters that can give rise to misunderstandings. The subject matter of this book is those Catholics who assisted the war effort, not those that did not. Advanced nationalists, the collection of radicals that included members of Sinn Féin, labour activists, suffragists, socialists, pacifists and others, are not the focus of this study. Historians have tended to categorize this group as one that was broadly anti-war and as Chapter 2 discusses, the vocal and demonstrative anti-recruitment activities of many of these radicals have been used as evidence to generalize about anti-war sentiment within Catholic Irish society at large. This book challenges this characterization of Irish society (indeed, it should be noted that there is a lack of scholarly work on the various individuals and groups that comprised Ireland’s advanced nationalists and how they felt about the war in each and every year of the conflict’s duration. To characterize all radicals as anti-war is thus a generalization which has not been tested). Nonetheless, Irish radicals are excluded from this study. The emphasis here is instead on the individuals who were not on the extremes and who have tended to be excluded from studies of the Irish revolutionary period; the individuals who formed the backbone of the war effort in Ireland.

This book argues that Irish Catholic support for the war effort lasted for longer than is commonly accepted across much of the existing literature. This does not mean that opposition to the war in Ireland was non-existent or that the traditional weighting of the importance of Sinn Féin as a political force is ‘wrong’. It may well mean, however, that historians of Ireland will have to recognize that there was a tradition of support and even sympathy for the British war effort which survived 1916 and 1918, support which was rendered in sections of Irish society (other than Protestant) and geographical areas other than Protestant parts of the North. It was this – together with the widespread familial legacies of personal involvement – that may have helped to provide the basis for the dramatic renewal of interest in the conflict in Ireland, and sympathy for those who took part in it, at the end of the twentieth century.

There was a surprising degree of cross-confessional cooperation in the war effort, which has gone virtually unnoticed in existing scholarly accounts and which this book brings to life. This does not mean that the political divisions between unionists and nationalists were insignificant, nor does it mean that a posture of hostility and actual violence played less of a role in preconfiguring the struggle for independence and the Northern Irish ‘Troubles’ that would disfigure the twentieth century. Rather, this book is about a constituency – and the sources suggest that it was a very sizeable constituency – that cannot be accommodated within the historiography of un ionism and nationalism, or the political history of 1916–23.

My book is instead about the people who took part in the phenomena it describes and analyses. It aims to provide a more complex picture of the Irish war effort, illuminating the changing dynamics of Catholic involvement. It is simultaneously a plea for a pluralistic view of twentieth-century Irish identities and attitudes, and, more pertinently, the history of Ireland and the Irish in the world’s first total war.

Irish civil society

How does one assess ‘support’ for the war effort among Catholics when a society as complex as Ireland did not have a single, uniform reaction to the conflict? As Catriona Pennell has noted, in 1914 the reactions of more than 40 million people across the whole of the UK were complex and ever-changing, and the same is true of the considerably fewer 4.4 million inhabitants of Ireland.17 However, broad trends and patterns of engagement with the war can still be detected when civil society is put at the centre of analysis.18 In the present analysis I use the notion of civil society as comprising a range of interacting groups that represent different interests.19 In wartime Ireland, these groups included elected public bodies (urban, district and rural councils, boards of guardians, corporations and harbour boards), interest groups (cooperatives, farmers’ unions, medical associations, political organizations and commercial representatives), faith groups (Catholic and Protestant associations), educational institutions (schools and universities), the press and philanthropic foundations (charitable associations and war-relief societies). Civil society represented the multiple divisions in Irish life including class, religion, age, sex and geography, which distinguished Ireland as a society. It is thus a lens through which one can view patterns and trends regarding Irish people’s engagement with the conflict.

To gain a more accurate understanding of the individuals involved in the war effort in Ireland, this book has made extensive use of the 1911 census of Ireland. Census data illuminates important background information on individuals involved in the war effort, including, among other factors, their religion, which in wartime Ireland was essentially a synonym for political persuasion. The long-standing ...