CHAPTER 1

A Lawyers’ War

Emergency Legislation and the Cyprus Bar Council

On February 27, 1957, as the war in Cyprus raged, the Labour Party peer Lord Strabolgi rose during a heated debate in the House of Lords. Criticizing Britain’s colonial government in Cyprus, Strabolgi demanded, “What sort of State is this? Is it a police State? Is it a State like that set up by Nazi Germany, or a State which is trying to copy the methods of Soviet Russia? I think that there is a very great need for the Government to investigate these allegations.”1 Put forward by a group of Greek Cypriot lawyers, the allegations in question criticized the use of emergency legislation to permit widespread press censorship, detention without trial, and abuse of prisoners in order to defeat the Greek Cypriot nationalist insurgency. These emergency regulations, which the Cyprus government adopted after the onset of violence in April 1955, were based heavily on those used to combat insurgencies in Malaya and Kenya. This draconian legislation was a common feature of postwar British counterinsurgency campaigns. Such laws facilitated counterinsurgency operations—particularly in the realm of intelligence collection through brutal interrogation measures.2

Scholars have viewed allegations of prisoner abuse in Cyprus from several perspectives. First, some commentators believe that the security forces usually did not abuse their powers but sometimes did so infrequently and only in exceptional circumstances.3 Taking a different view, other scholars have argued that the allegations were credible.4 Offering a variation on this interpretation, the historian David French argues that there is strong evidence of abuse, but EOKA propaganda (see below) exaggerated the extent of British brutality. French’s interpretation is accurate but incomplete. EOKA certainly exaggerated British cruelty for propaganda purposes and British abuses clearly occurred, but torture was not primarily the result of increased frustration, nor was it limited to a small number of undisciplined “bad apples.” Allegations of torture overwhelmingly concerned Special Branch interrogations, suggesting that prisoner abuse was part of a calculated effort to obtain vital intelligence via coercive interrogation methods.5 The Cyprus government’s tough emergency legislation facilitated these intelligence collection efforts.

In response, Greek Cypriot lawyers’ rights activism transformed the legal system into a battlefield in which both sides sought to manipulate the law to their advantage. These lawyers resisted the effects of the emergency regulations by defending detainees in court. But they soon realized that courtroom advocacy did not accomplish enough in the face of a judicial system stacked in Britain’s favor. The lawyers then organized through their professional association, the Cyprus Bar Council, to protect detainees’ rights. They lobbied colonial officials to establish and enforce the right of detainees to legal representation and the confidentiality of attorney-client relationships; publicized British cruelty when such standards were not met, including through complaints to members of Parliament in Britain; and documented cases of prisoner abuse for inclusion in international legal proceedings at the European Commission of Human Rights. These lawyers turned advocacy for detainee rights into a form of resistance to colonial authority that they framed as human rights activism.6 Greek Cypriot lawyers’ efforts convinced senior colonial officials—including the colonial secretary and Cyprus governor—to develop new ways of countering rights-based criticisms. This chapter examines the origins of the war in Cyprus and how the contest over emergency laws shaped counterinsurgency policies and practices up to the spring of 1957.

Enosis and the Cyprus Insurgency

The Cyprus insurgency began on April 1, 1955 over the Greek Cypriot desire for “enosis,” or union, with Greece. Led by the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters, known by its Greek abbreviation EOKA, pro-enosis Greek Cypriots waged a nearly four-year war against their British colonizers. EOKA was commanded by a Cypriot-born retired Greek army colonel named George Grivas. Having fought in Greece’s 1919–22 war with Turkey and in the Second World War, Grivas was an experienced officer who had been laying the groundwork for an insurgency in Cyprus since 1951. In contrast, when the war began, British forces were unprepared for a large- scale insurgency. After eight months of fighting, British officials had replaced an ineffective colonial governor with an experienced military commander who declared a state of emergency and enacted a harsh set of laws.

British forces had a difficult time subduing the insurgency in part because the overwhelming majority of Greek Cypriots supported enosis.7 As over three-fourths of the five hundred thousand people living on Cyprus were Greek Cypriot, British forces faced a difficult task in subduing the insurgency. By 1957, violence between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities had erupted as Turkish Cypriots, who comprised approximately 18 percent of the island’s population, asserted their desire for partition of the island rather than union with Greece. As the conflict descended into civil war, Greece and Turkey grew increasingly assertive in seeking to protect the interests of the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities, respectively.8

The involvement of Greece and Turkey ensured that an international settlement would be required to end the conflict. The war drew to a close after Greece, Turkey, and Britain, as well as the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, agreed to the establishment of an independent republic of Cyprus in which political power would be shared among Greek and Turkish Cypriots. In February 1959, these parties to the conflict signed the London and Zurich Agreements. The London Agreement ended the conflict between Britain, Greek Cypriots, and Turkish Cypriots. Britain, Greece, and Turkey signed the Zurich Agreement, which stipulated that neither union nor partition could occur without Greek and Turkish concurrence.9

Enosis supporters did not achieve their goal of unity with Greece, but they waged an effective insurgency that killed 371 British soldiers. Organized as semi-independent cells, EOKA units conducted assassinations, bombings, and ambushes and ran a complex propaganda operation to maintain support for the war among Greek Cypriot civilians. Although British forces developed a sophisticated understanding of EOKA’s organizational structure, when the war began, British troops had a difficult time countering the insurgency. In November 1955, with violence mounting, the Cyprus government declared a state of emergency.10

The insurgency gathered momentum throughout the summer of 1955. EOKA attacked Greek Cypriot police officers, whom Grivas deemed antinationalist “traitors.” Special Branch also emerged as a key EOKA target because of its intelligence collection mission. Without good intelligence, government forces would not be able to counter EOKA attacks. The Cyprus government, headed by Governor Sir Richard Armitage, had not expected a coordinated insurgent campaign. With the outbreak of violence, the British army arranged for Sir Gerald Templer, the officer who had served as high commissioner and military commander during the successful counterinsurgency campaign in Malaya, to visit Cyprus and assess the situation. Templer felt that Armitage’s government was not taking the situation seriously enough and criticized them for carrying on with business as usual. He decided that Armitage was incapable of handling the situation. Templer also discovered that Special Branch, the organization responsible for intelligence collection, was woefully undermanned and unprepared. Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden shared Templer’s frustrations. Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan likewise argued that “we cannot afford to give any impression that we are on the run in Cyprus” because of the island’s importance in British Middle East policy. Without the island as a base, Britain’s ability to project power in the Middle East—a vital region because of its oil reserves—would be severely compromised.11

After Templer’s visit, Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd decided to replace Sir Richard Armitage with someone deemed more capable of combating the insurgency. The sense in Whitehall was that the situation demanded a “military man” to coordinate political and military activities as Templer had in Malaya. Field Marshal Sir John Harding was the logical choice. At the time of his October 1955 appointment as governor of Cyprus, Harding was the chief of the Imperial General Staff—the highest position in the British military. He was one of the most senior officers in the armed forces and an experienced commander. In a previous assignment as commander-in-chief, Far East Land Forces, he had worked with Templer during the Malayan Emergency. According to one scholar, the idea that terrorists and insurgents should be dealt with harshly “was not just an assumption of Harding’s, it was one of his deepest feelings.”12 Harding approached his work in Cyprus with a hard-nosed determination to eradicate the insurgency through whatever means necessary.

While Harding understood that military action alone would not solve the conflict, he believed that a political solution could be reached only if British forces first destroyed EOKA. His objective was to obtain a settlement in which Greek and Turkish Cypriots agreed on a new constitutional framework of local self-government under British colonial rule.13 This conviction was based on two assumptions: Harding thought that only a minority of the Greek Cypriot community actively supported EOKA and that the group maintained its influence by intimidating the rest of the more moderate population. To eliminate EOKA’s hold, Harding planned to capture or kill EOKA fighters while coercing the population into submission. To do so, Harding determined that “it will be essential to employ the sternest and most drastic forms of deterrent open to us.” He concluded that “one of the results of the various measures such as collective fines, curfews and other restrictions that have recently been increased is the restoration of respect” for British authority.14 If EOKA could intimidate the Greek Cypriot population into submission, so could the British.

When Harding decided to declare a state of emergency in November 1955, Colonial Secretary Lennox-Boyd agreed but also sounded a cautionary note. Lennox-Boyd encouraged Harding, writing that “important though it is to seize any chance of a political solution [to the conflict], you must not let this hope interfere with firm action.” Lennox-Boyd concurred with Harding’s wish to eliminate EOKA but worried that tough measures could cause public controversy that he was keen to avoid. Even so, Lennox-Boyd had known Harding for many years and trusted his judgment. He authorized Harding to use collective punishments and order judicial whipping of juvenile offenders but urged him to be careful about using these powers. Lennox-Boyd did not want the Cyprus conflict to cause public controversy. He told Harding that “as you know, some forms of collective punishment have an ugly ring here.” Collective fines and punitive seizures of civilians’ property would “present real political difficulties” for the Colonial Office. Harding reassured Lennox-Boyd that he would “proceed as discreetly as the situation permits,” and he declared a state of emergency in Cyprus on November 26. Harding knew that he had Lennox-Boyd’s support in taking tough measures, but he also knew that there were limits as to what politicians in Britain would allow.15

The Emergency Regulations

Under the state of emergency, Harding’s powers were nearly absolute. These powers were based on the First World War–era Defence of the Realm Acts (DORA), which permitted the executive to enact regulations concerning public safety without necessitating Parliament’s approval. The 1921 Restoration of Order in Ireland Act applied similar provisions to Ireland after the First World War. Beyond this legislation, the government could amend legislation through the orders-in-council procedure. Akin to an executive order, an order-in-council could establish regulations that held the force of law without being submitted to the legislature for approval. Together, DORA, the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, and orders-in-council formed the legal basis of Harding’s emergency powers. By the time he faced the insurgency in Cyprus, emergency regulations regimes had become a common feature of colonial rule, having been employed in Ireland, Palestine, India, Malaya, and Kenya.16

Harding enacted seventy-six new laws that permitted security forces—a term that British officials used in reference to both police and military units—to wield significant coercive powers. Security personnel were authorized to arrest without warrant any person who was believed to have “acted or was about to act, in a manner prejudicial to public safety or public order, or who had committed or was about to commit an offence.”17 Any officer in the rank of major or higher could approve the detention of an arrested person for up to twenty-eight days without charges. Harding had the authority to sign a detention order extending any individual’s imprisonment indefinitely and to deport anyone from the colony. Based on a similar measure passed during the Malayan Emergency, the Cyprus legislation also designated certain “protected areas” off-limits to all Cypriots except those with special government passes. Anyone in a protected area who fled from security forces could be shot.18 Harding intended to use the emergency legislation regime as a tool for facilitating the collection of intelligence and for separating the Cypriot population from the insurgents by disrupting communication and supply between insurgents and civilian supporters.19

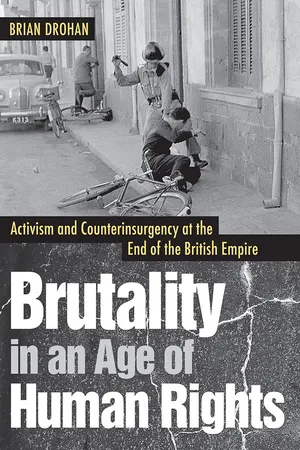

These regulations severely hampered civilians’ freedom of movement and allowed the government to censor information available to the populace. Cypriots had to register with the government and obtain an identity card. Soldiers and police could demand to see this card at any time—failure to produce it when ordered could result in a fine or imprisonment. District commissioners could ban civilians from congregating in public spaces, close shops, and requisition property. Censorship regulations permitted government censors to regulate mail sent to or from any person in the colony and to control the content of radio broadcasts and newspaper reports. Propaganda—such as signs, slogans, graffiti, banners, and flags bearing political messages—was prohibited.20 The Limassol district commissioner also outlawed the use of bicycles without a permit because EOKA fighters often used bicycles as “get-away vehicles.” Other district commissioners followed suit.21 Bicycle bans targeted teenagers and young adults—the primary demographic involved in EOKA attacks.22

Harding authorized the use of curfews and collective punishment as means of coercing local populations into submission. Curfews restricted movement in towns and could last for several hours or several weeks. An army report completed at the end of the conflict co...